Tuesday 16 March 2021 1:47pm

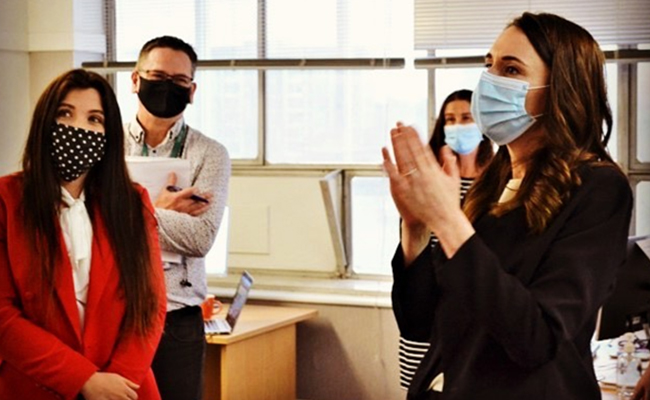

Talking theories about community outbreak spread with Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern.

Ten years after helping in the Christchurch earthquake as a medical student, an Otago alumna is playing a key role in another national health emergency.

Dr Felicity Williamson is only half-joking when she describes herself as a public health detective, a pandemic “beat cop”.

“I don't know exactly why I chose Public Health. I know that my skill set lent itself to some of these more systemic issues. It was a possibly little bit of wanting a more balanced lifestyle. I wanted to think about the kind of life I wanted to create. I do like efficient interventions and I like thinking about community and people as a whole. That more holistic view of medicine.”

Technically her job as a Public Health Medicine Specialist involves “COVID-19 source investigation” but framing it in terms of police work is not too much of a stretch.

The Otago alumna is on the frontline of New Zealand’s pandemic response, reacting to the latest COVID-19 cases – hunting down clues and piecing together evidence.

“Most of my work is like detective work, trying to understand how transmission may have occurred between returnees, between returnees and staff, between staff and the community and between returnees and the community. Trying to find out what happened – and what we can do better.”

When you read about the latest case in the media, there is a good chance Felicity and the public health unit team she works with have had a hand in piecing together the jigsaw into a coherent narrative. Their systems pull together information around testing and movements but there’s also the people element – figuring out how the disease intersects with human behaviour.

“I have to know where people were, how they behave and what are the key risks in those environments. So, I have to know about the disease, but I also have to know a lot about people, which is super important.

“You don't always find what you’re looking for. We have to exhaust every option and find out everything we can and in the end be ok with the fact that we may not know exactly what happened. But we can still put in place things to reduce future risk.”

Dr Felicity Williamson

Felicity’s day-job is as a Public Health Medicine Specialist for consultancy company Synergia. The detective work stems from a secondment to the Auckland Regional Public Health Service, being involved with the operations of contact tracing as well as gathering intel for COVID-19 outbreaks.

Attached to the Auckland Regional Isolation and Quarantine Coordination Cell, she has been involved in all the headline-making COVID cases – the Rydges Hotel worker, the Jet Park facility, the New Zealand Defence Force case and the recent community clusters.

“I'm the eyes and ears on the ground of what's actually happening in managed isolation and if we do need a source investigation that involves managed isolation – which really is most of them now as there aren’t many other ways COVID-19 can enter NZ – I have a leadership role in those.”

Her reports, containing recommendations on improving processes, go all the way to top. Public Health has never had a higher profile but having her words land on the Prime Minister’s desk is possibly not what Felicity imagined when she chose her career path.

“I don't know exactly why I chose Public Health. I know that my skill set lent itself to some of these more systemic issues. It was a possibly little bit of wanting a more balanced lifestyle. I wanted to think about the kind of life I wanted to create.

“I do like efficient interventions and I like thinking about community and people as a whole. That more holistic view of medicine.”

After graduating from Otago Medical School, Felicity gained a Master of Public Health at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine where she learned “all the real nitty gritty parts of public health epidemiology, health promotion and health economics.”

Returning to New Zealand, she then completed a second Master of Public Health at the University of Auckland.

Her job at Synergia has a broad focus, targeting the improvement of systems and processes across the health sector.

“No day is the same. You might be working on very different programmes in parallel. You have to jump between the two and become very agile. And you have to use all sorts of things from your clinical training …. As a doctor you know the environment, the people and the pressures and often clinicians like to talk to other clinicians.”

Felicity at Med School O-week in 2008.

Student days and the Christchurch earthquakes

Felicity grew up in Queenstown and at first found the transition to university life in Dunedin “very daunting”.

“It depends what happens with our vaccines and what happens with global borders but as long as COVID is around and our plan is to keep it out, then we will be needing managed isolation. We don't want to talk about it or think about it but if we are in this situation again with another novel pathogen then we will also need to consider how we manage that.”

“But I was lucky in my first year in Carrington Hall that they have houses, and I was in a smaller house, so it felt a little bit more homely and not so overwhelming.”

Health Sciences Year One was tough but, interestingly, her best mark was in epidemiology, pointing the way to her future career.

She completed her clinical training at the University of Otago, Christchurch, and can clearly remember where she was when the deadly February 2011 earthquake struck.

“I was in the computer room up on the fifth floor of the School of Medicine building. I remember when it started shaking – and of course we were all primed because of the December one in the middle of the night. But we all looked at each other and thought ‘this isn't stopping and we are very high up. We need to get out of here.’

“There was plaster falling in the stairwell while we were going down, I remember that.”

She made it out of the building and safely home to her nearby flat. As the situation unfolded, a group of the young doctors went to Christchurch Hospital and offered their services.

They organised a roster and took on many of the basic tasks such as moving patients and ferrying forms and patients around the hospital, “whatever would make things quicker for the medical teams”.

“It was all quite chaotic and at times we would be watching TV in the staff room just to give an indication to the teams that there were survivors, and we might have patients coming in the next 20 minutes.

“There were some terrible things but in medicine you see terrible things every day and I would say my medical oncology run was probably more confronting and upsetting. I think when you're a doctor you're exposed to trauma and you're exposed to death. Even as a medical student you're exposed to all these things so I guess your threshold changes.”

Felicity is passionate about fitness and has qualifications which include personal training, group fitness, yoga and Pilates

Outside of work, Felicity is passionate about fitness and has qualifications which include personal training, group fitness, yoga and Pilates.

“It keeps me sane. I teach at different gyms and it’s a lot of fun.”

As for her work, the demand for Public Health expertise doesn’t look like it’s going away any time soon.

“It depends what happens with our vaccines and what happens with global borders but as long as COVID is around and our plan is to keep it out, then we will be needing managed isolation. We don't want to talk about it or think about it but if we are in this situation again with another novel pathogen then we will also need to consider how we manage that.”