Friday 3 March 2017 2:18pm

Friday 3 March 2017 2:18pm

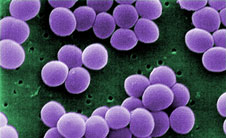

Staphylococcus aureus

New Zealanders should not be complacent because we have fewer antibiotic-resistant bacterial pathogens than elsewhere in the world, a University of Otago expert says.

Professor of Biochemistry Kurt Krause says New Zealand's relative good fortune in its lack of antibiotic-resistant pathogens – listed this week by the World Health Organization (WHO) – provides the perfect window for research and development of new treatments.

“This is not a time to be sitting on our hands. It goes without saying that we are behind in this struggle and the time for doing this work has to be now.”

It is also a time for the carefully considered use of antibiotics, according to a senior lecturer in Otago's Department of Microbiology and Immunology, Dr James Ussher.

“Prudent use of antibiotics, both in hospitals and the community, is an important measure to reduce selection pressure for the spread of these organisms.

“However, at a population level, the rate of antibiotic prescribing in New Zealand increased by 49 per cent from 2006 to 2014 and is higher than 22 out of 29 European countries, suggesting there is significant room for reductions.

“More investment is required from the Government and DHBs to ensure prudent use of antibiotics. Good infection-control practices, including cleaning, hand hygiene and isolation of infected patients, are also crucial to controlling spread.

“It is critical that hospitals remain vigilant for the introduction of these infections, as the risk is only going to increase,” Dr Ussher, also a consultant clinical microbiologist at Southern Community Laboratories, says.

The global WHO list, compiled using software co-invented by Associate Professor Paul Hansen of Otago's Department of Economics, splits into three priority groups all the resistant organisms which have featured prominently in medical and media reports and also some lesser known bacterial pathogens.

Priority 1 pathogens include Acinetobacter, Pseudomonas and Enterobacteriaceae, all resistant to the most powerful antibiotics, and some strains that are almost untreatable.

Professor Krause says fortunately the most highly resistant strains, which are not sensitive even to drugs of last resort such as colistin or tigecycline, have not yet been reported here.

“Although this is good news, it is important not to become complacent. Because of globalisation, antibiotic resistance of even the most severe nature can arrive at any airport or port at any time. And in general, resistant strains usually spread across the world in time.”

For New Zealanders, the most important members of the list include the Priority-2 graded Campylobacter and Staphylococcus aureus, and the Priority-3 Streptococcus pneumoniae, he says.

“Campylobacter, an important cause of gastrointestinal disease, continues to dominate the list of New Zealand reportable diseases, with a rate of about 150 cases per 100,000 population. However, some clinicians feel this is an underestimate, with as many as one per cent of New Zealanders having this illness yearly.

“Significant numbers of Streptococcus pneumoniae and Staphylococcus aureus infections also occur annually in New Zealand.

“Each year about 100,000 people here are hospitalised with infection as the primary cause, and this represents about 10 per cent of all hospitalisations. More than 60 per cent of these infections are bacterial in nature, when the cause can be determined. This suggests that controlling bacterial disease is an important goal in New Zealand.

“Levels of antimicrobial resistance in New Zealand are, for most of the pathogens on the list, between three and 10-fold less than the most affected countries,” Professor Krause says.

The Priority-2 group also includes Neisseria gonorrhoeae, of which strains have become resistant to multiple drugs, “raising the spectre” of an untreatable sexually transmitted infection.

Dr Ussher says resistance to carbapenems - the broadest spectrum antibiotics available and the antibiotic of last resort – is currently rare in New Zealand.

“However, cases imported from overseas are increasingly being reported and episodes of limited patient-to-patient transmission have occurred in New Zealand hospitals.”

The WHO used Associate Professor Hansen's 1000Minds software to prioritise the bacteria of greatest threat to humans and in need of research. The software helps in multi-criteria decision-making, in allocating resources and in conjoint analysis.

For more information, please contact:

Professor Kurt Krause,

Department of Biochemistry, University of Otago

Tel 64 03 479 5166

Email kurt.krause@otago.ac.nz

A list of Otago experts available for media comment is available elsewhere on this website.

Electronic addresses (including email accounts, instant messaging services, or telephone accounts) published on this page are for the sole purpose of contact with the individuals concerned, in their capacity as officers, employees or students of the University of Otago, or their respective organisation. Publication of any such electronic address is not to be taken as consent to receive unsolicited commercial electronic messages by the address holder.