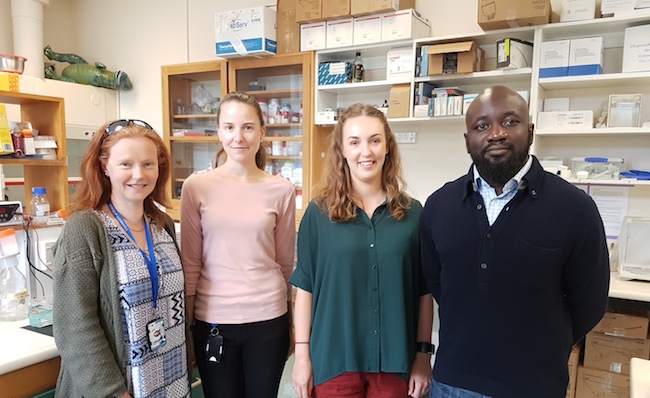

Dr Stephanie Hughes and her colleagues in the Otago Department of Biochemistry have been developing special viruses as a gene therapy treatment for Batten disease.

|

| From left: Dr Stephanie Hughes and students Stephanie Mercer, Sophie Mathison and Oluwatobi Eboda in the Neurodegenerative and Lysosomal Disease Lab. |

To correct for the mutation in the CLN5 gene of people with Batten disease, the normal gene needs to be injected into thousands or even millions of cells where it is needed.

If you simply insert a gene directly into a cell, it usually does not function. Viruses naturally inject their DNA into cells in a way that allows the genes in the DNA to help make proteins.

Read more about viruses on the Science Learning Hub.

The viruses used in gene therapy are modified so they can't cause disease.

Three types of viruses can be used: retrovirus, adenovirus, or adeno-associated virus (most commonly used). All of these viruses introduce their DNA into the nucleus of a cell; retroviruses integrate their DNA into one of the cell's chromosomes, whereas adenoviruses and adeno-associated viruses do not.

|  |  |

| Electron micrograph of retroviruses (GrahamColm / English Wikipedia / CC BY 3.0). | Electron micrograph of adenoviruses (PhD Dre / English Wikipedia / GFDL or CC BY-SA 3.0 / via Wikimedia Commons). | Electron micrograph of adeno-associated viruses (Kenneth Raj Research Group, formerly of the NIMR, UK; MicrobeWiki). |

Dr Hughes has been using lentivirus, a type of retrovirus, and adeno-associated virus to create and test gene therapy for treating Batten disease in sheep and mice.

Before the gene therapy can be tested on human patients, a lot of research needs to be done in the lab.

There are three main parts to this research:

- Make the gene therapy virus.

- Test the gene therapy on cells cultured in a dish.

- Test the gene therapy in an animal model, in this case on sheep who naturally already have the Batten disease mutation.

1) Make the gene therapy virus

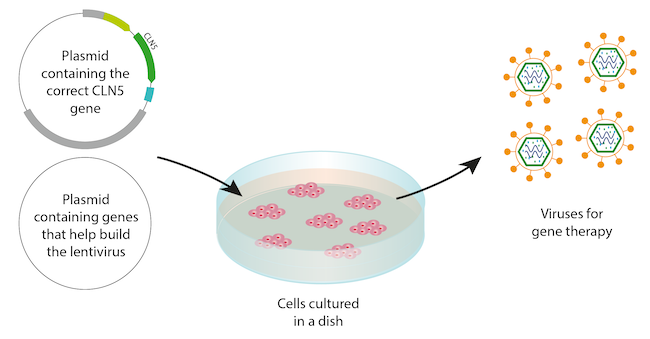

To make the virus, the researchers need a DNA plasmid (a circle of DNA) which contains the correct CLN5 gene, and cells cultured (grown) in a dish inside an incubator. The cells sit in media, which is a liquid containing the nutrients they need to stay alive.

The researchers make the plasmid using:

- restriction enzymes - 'scissor' proteins that cut DNA into pieces

- ligases - 'glue' proteins that stick pieces of DNA together

- polymerase chain reaction (PCR) or DNA cloning - techniques which make multiple copies of the plasmid

Watch an animation of a restriction enzyme and a ligase at work on a DNA plasmid here.

Next, the researchers add the plasmid to the dish of cultured cells, along with another plasmid that contains genes that help build the lentivirus, and a chemical that makes the cell membranes a little leaky.

The cells take up the plasmid DNA through their leaky membranes, and turn into little virus-making factories, spitting out the finished virus particles into the media.

Finally, the researchers harvest the viruses from the media, which are ready to be used in gene therapy trials.

|

| Making viruses using plasmids and cultured cells. |

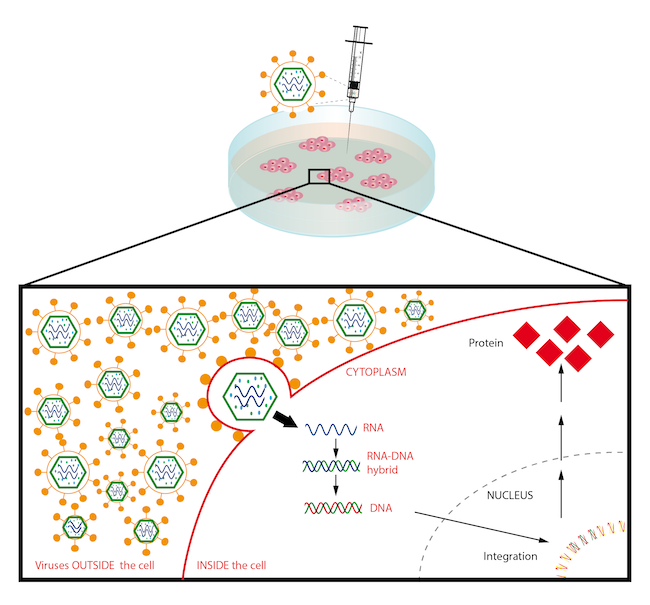

2) Test the gene therapy on cells

To see whether their gene therapy viruses work, the researchers add them to a different culture of cells. These cells were taken from sheep with Batten disease and cultured in a dish. They have a mutated version of the CLN5 gene and are not well; you can see that their lysosomes don't work very well if you look at them using a microscope and special fluorescent dyes.

If it works, the virus transfers the correct CLN5 gene to the nucleus of the cells, integrating it into their chromosomes. The cells then start to produce the correct CLN5 protein:

|

| How the gene therapy virus works on cells to correct the mutated gene. |

The researchers are able to see whether the gene therapy works successfully by comparing treated sick cells with untreated sick cells and untreated normal cells under a microscope. In their experiments, the gene therapy-treated cells started to look more like normal cells.

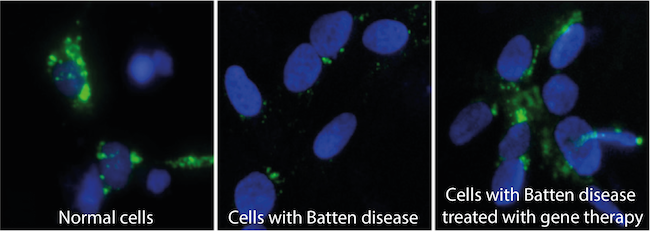

These are photos of cells from one of the experiments in the Hughes Lab:

The blue round shapes are the nuclei of cells, stained blue using a fluorescent dye. The green spots show where lysosomes are working properly, carrying out a process called autophagy.

You can see that there are lots of green spots on the picture of the normal cells (left), i.e. the lysosomes in those cells are working normally.

In the cells with Batten disease (middle), the lysosomes are not working very well and have very few green spots.

The cells with Batten disease that have been treated with the virus gene therapy have lots of green spots, and look much more like the normal cells.

3) Test the gene therapy on an animal model

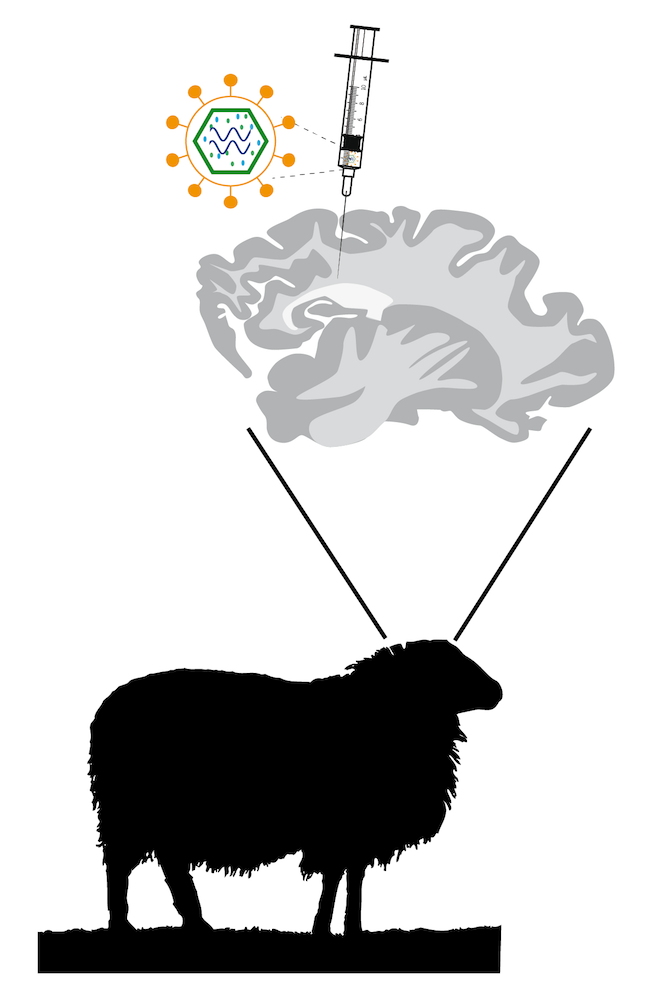

Once it was clear the gene therapy viruses were working on cells cultured in a dish, Dr Hughes and her collaborators next tested the gene therapy viruses on a flock of sheep at Lincoln University, New Zealand, that naturally develop Batten disease.

The animals have a mutation in their CLN5 gene, as do many humans with Batten disease, and share many of the features of the human disease, including neurodegeneration, blindness and premature death.

The sheep chosen for treatment had not yet developed symptoms of Batten disease.

The researchers injected the viruses into the fluid-filled spaces in the sheep brains. The viruses then "infected" the brain cells, integrating the normal CLN5 gene into the cells' genomes.

Promisingly, the treated sheep lived longer than the untreated sheep, and they did not develop most of the Batten disease problems, apart from some loss of vision.

A clinical trial has now started for the CLN6 form of the disease on human patients with collaborators in the USA (see also curebatten.org).

Next: Biological implications of gene therapy

Previous: Gene therapy - a cure for Batten disease?