StBathans blue lake and how it got there.pdf (pdf version of this page).

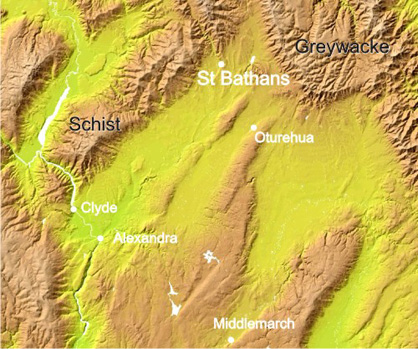

Blue Lake, at the foot of Mt St Bathans in Central Otago, is one of several important historical gold mines in the area. Mt St Bathans is made up of 200 million year old greywacke and that continues deep under the Blue Lake area. It is unusual to find gold associated with greywacke, and it was a long and complicated geological journey that ended with the large concentrations of gold where St Bathans town now stands.

St-Bathans - Blue Lake

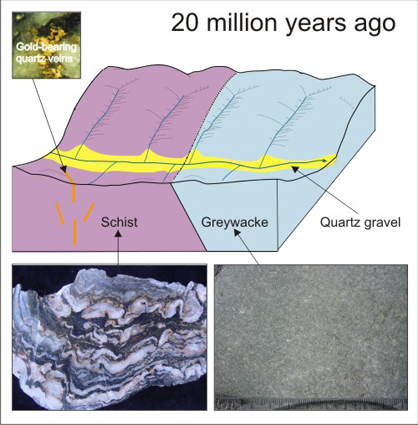

Gold typically occurs in quartz veins in schist (see diagram below). Schist bedrock and gold-bearing veins occur tens of kilometres to the southwest of the St Bathans area. Greywacke was faulted against schist about 100 million years ago. About 20 million years ago, erosion of schist hills produced river sediments rich in quartz pebbles. The quartz pebbles result when the white quartz layers in schist break up and become rounded during river transport. Some of the quartz came from gold-bearing veins, and the gold was transported at the same time. The quartz pebbles and gold were transported northeast and deposited on greywacke bedrock. Some greywacke pebbles entered this river, but they are not resistent to abrasion like quartz and most of them ground away.

Blue lake area at 20 million years ago

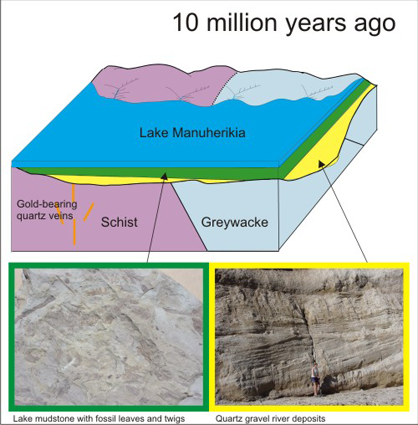

Blue lake area at 10 million years ago

Ten million years ago, the quartz river sediments were buried by a large shallow lake, Lake Manuherikia, which covered most of Central Otago. The lake sediments preserved leaves of the local vegetation (including eucalyptus) and bones of animals such as lizards and small mammals. The lake sediments were, in turn, buried by gravels from the mountains that we see today. These mountains began to rise about 5 million years ago. The resultant greywacke gravels progressively filled the lake, on the margins of the mountains.

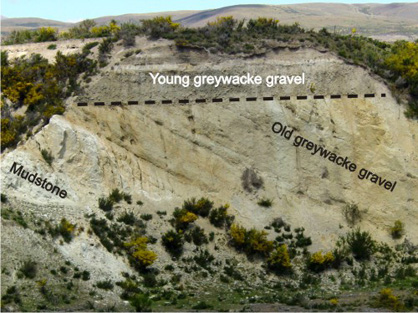

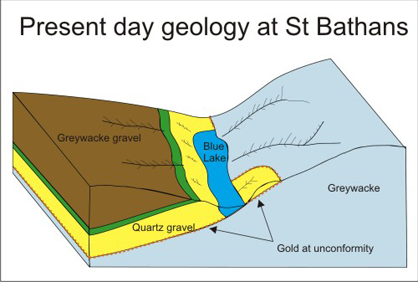

Continued uplift caused tilting of the greywacke gravels, and the underlying quartz gravels and mudstones. Even younger gravels, associated with modern rivers, deposited new gravels on top of the older tilted sediments. Gold from the eroding quartz gravels accumulated at the boundary (unconformity) between the gravel sequences (so-called “Maori Bottom” of the old miners).

Tilted mudstone and greywacke gravel (5 million years old) with younger greywacke gravels on top. Gold occurs at the boundary.

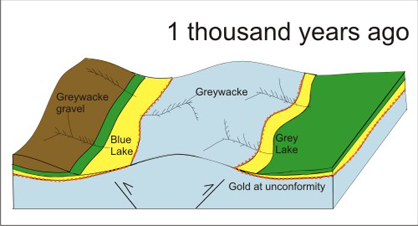

Blue lake area at 1 thousand years ago

1. Quartz gravel

1. Quartz gravel  2. Alluvial gold from quartz gravel river deposits

2. Alluvial gold from quartz gravel river deposits  3. Pink baked sediments and grey melted sediments

3. Pink baked sediments and grey melted sediments

As the mountain-building tilted the old river and and lake sediments, it also affected the underlying greywacke bedrock. In the St Bathans area, a greywacke ridge was pushed up along the Blue Lake Fault which trends northwest from Oturehua. As that ridge was pushed up, the sediments were tilted so that they slope southwest on the St Bathans side, and slope northeast on the other side, where Grey Lake is now.

The quartz gravels were eroded into younger river deposits as the ridge was pushed up. Gold in the modern streams alerted the original prospectors to the deposit at St Bathans.

Plant material withing the pile of quartz gravels had formed lignite during burial. When that lignite was exposed during uplift, and subsequent mining, many lignite seams ignited and some burnt for many years, baking the surrounding quartz sediments red and brown like bricks (as on the road down to Blue Lake).

Present day geology at St Bathans

The erosion surface where quartz gravels rest on bedrock (called an “unconformity” by geologists, and a “bottom” by gold miners) is the most important geological feature in the story of gold mining in the St Bathans area. The gold was concentrated near the bottom of the quartz gravels at and near the greywacke erosion surface.

The gold miners followed this surface downwards from the greywacke ridge, sluicing the rest of the quartz gravels and lake sediments out of the way. The greywacke surface is soft because groundwater from the quartz gravels altered the greywacke to clay. Hence, some of the greywacke was sluiced away as well. The miners followed the gold-bearing surface down the slope until they couldn't raise the gravel any more, and couldn't drain the area. As soon as they stopped mining, the hole filled in with water, and Blue Lake formed. An unknown amount of gold-bearing gravel still exists beneath St Bathans town and the hills to the southwest. A mirror image of this geological and mining situation occurred on the other side of the greywacke ridge, to form Grey Lake.

Blue Lake and exposed mining surface

Grey Lake from the north-west

Topographic map of Central Otago