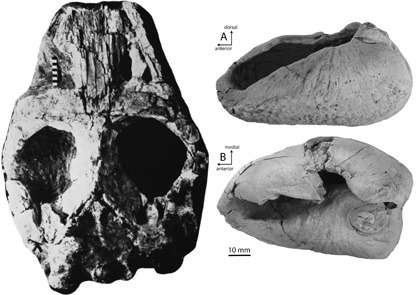

Skull and earbone (tympanic bulla) of “Mauicetus” lophocephalus.

In the 1930s, or possibly earlier, a large chunk of bone was discovered in limestone at the Milburn Quarry near Milton in Otago (South Island, New Zealand). This block made it into the hands of University of Otago zoology professor W. B. Benham, who recognized that it was a skull of a cetacean - and in 1937 named it Lophocephalus parki, and assumed it was from a late surviving archaeocete whale. Later correspondence with other paleontologists abroad led him to realize that the name Lophocephalus was preoccupied by a beetle, and that the fossil actually represented a baleen whale - and he renamed it Mauicetus parki. In the 1940s and 1950s, Otago zoology professor Brian J. Marples began discovering a series of better preserved specimens of fossil whales in Oligocene marine rocks of the Waitaki Valley region of North Otago; three of these specimens were judged to be similar enough to be placed in the same genus, and he named these Mauicetus brevicollis, Mauicetus lophocephalus, and Mauicetus waitakiensis. The latter of these, M. waitakiensis, has recently been reinterpreted as representing a new genus of eomysticetid baleen whale (Tohoraata; see webpage on Tohoraata). Mauicetus lophocephalus had by far the most well preserved material, consisting of one half of a skull including the braincase and the base of the snout as well as earbones, a partial mandible, and many vertebrae. At the time of discovery, M. lophocephalus was the only anatomically informative archaic baleen whale to bridge the immense gap between Eocene archaeocetes and derived Miocene baleen whales - exhibiting toothless jaws like modern baleen whales, but an anteriorly placed blowhole, enormous attachment areas for jaw muscles and a tiny braincase as well as primitive earbones and an elongate neck. Unfortunately, the skull was misplaced sometime in the 1960s and has never been recovered, hampering informed discussion of this problematic taxon and its significance in whale evolution.

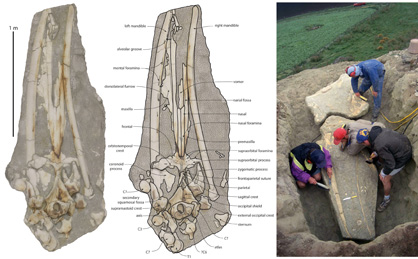

Holotype skull of Tokarahia kauaeroa (OU 22235), as prepared (left) and under excavation in North Otago. Photos of fieldwork © R. Ewan Fordyce.

In the mid 1990s, Otago U. professor Ewan Fordyce excavated several new specimens similar to M. lophocephalus, including a rather large partial skeleton including a nearly 2 meter long skull with mandibles, the neck and thoracic vertebral column, ribs, and most of both flippers including the scapulae, humeri, ulnae, and a radius. This enormous fossil had to be excavated out of a limestone cliff in North Otago over several days using a large field crew and heavy machinery, digging 3-4 meters into the cliff in order to recover the fossil in two large plaster jackets. Once prepared, it was clear that the fossil was similar to M. lophocephalus - and critically preserved most of the skull in addition to the earbones, mandible, and vertebrae - the only surviving (and thus comparable) bones of M. lophocephalus, permitting reassessment of Brian Marples' species. A few years later similar fossils were discovered in the Oligocene of South Carolina and named Eomysticetus and Micromysticetus. Mauicetus lophocephalus, and what would eventually be renamed as Tohoraata waitakiensis - were eomysticetids, the earliest group of toothless baleen whales, and the earliest whales that relied wholly on filter feeding for sustenance. In the meantime, a new skull from a lime quarry in South Canterbury shed light on the anatomy of the original species Mauicetus parki, which is not an eomysticetid, but a much more "advanced" type of whale that is more similar to modern baleen whales. This meant that M. lophocephalus was not Mauicetus, and needed a new genus name - and so it was renamed Tokarahia lophocephalus, and the new skeleton named as the new species Tokarahia kauaeroa. "Tokarahia" refers to the nearby township of Tokarahi, whereas "kauaeroa" means "long jaw" in Māori, referring to the nearly 2 meter long mandibles of the type specimen.

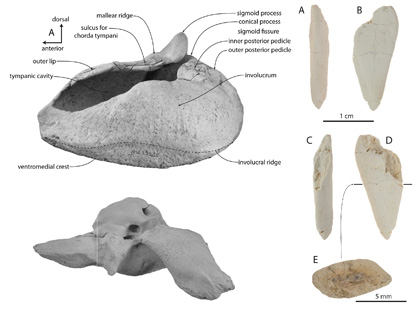

Earbones (tympanic bulla, top left; periotic, bottom left) and tooth (right) of Tokarahia.

The skull of Tokarahia kauaeroa includes an elongate, triangular and delicate snout - and some of the bony connection between bones of the snout are loose like modern baleen whales, whereas others are rigid - an intermediate condition between the kinetic palates of modern baleen whales and the rigid snouts of toothy archaeocete whales. The blowhole being positioned far forward on the skull, and teeth appear to be absent from most of the palate and instead baleen appears to have been present - though baleen is a soft tissue and does not fossilize. Most surprisingly, a referred skull of Tokarahia lophocephalus preserved a single, partial tooth, though not preserved in the snout - it is a small, peglike tooth that was most likely vestigial and probably positioned at the tip of the snout. Baleen-bearing eomysticetids from elsewhere were assumed to be completely toothless by virtue of having flattened, grooved palates, though these other fossils did not preserve the tip of the snout where these teeth would have been present. Indeed, Tokarahia kauaeroa preserves several tooth sockets in the tips of the mandibles, suggesting several upper and lower, peglike teeth with no probable function in feeding.

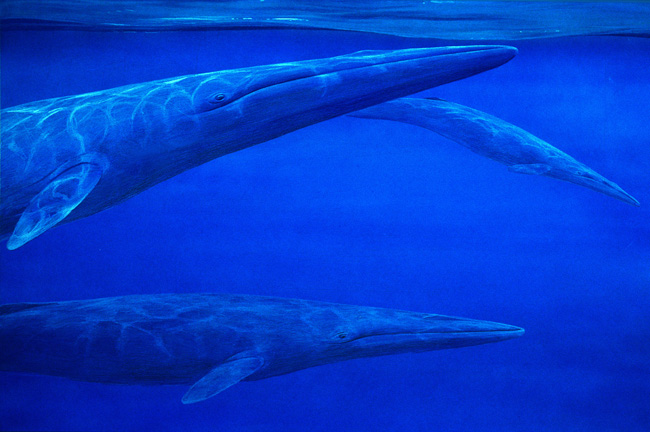

Life restoration of Tokarahia. Artwork by Chris Gaskin, ©Geology Department, University of Otago.

Discovery of Tokarahia kauaeroa has elucidated the skeletal anatomy of transitional baleen whales, expanded the diversity of eomysticetids, and finally revealed the phylogenetic affinities of “Mauicetus” lophocephalus, now Tokarahialophocephalus. Both species are found in the same horizons indicating they coexisted alongside several other eomysticetids and a host of other fossil cetaceans.

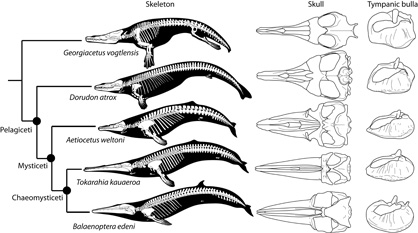

Skeletal evolution of baleen whales showing the new eomysticetid Tokarahia, a modern baleen whale (Balaenoptera edeni), a toothed mysticete (Aetiocetus), and two archaeocete whales (Georgiacetus, Dorudon). Artwork by Robert W. Boessenecker.

This study formed part of Robert Boessenecker's doctoral thesis in the University of Otago Department of Geology, and was funded by a University of Otago Doctoral Scholarship and fossils of Tokarahia were collected during fieldwork supported by a grant from the National Geographic Society.

3D models of Tokarahia

Models were generated using Agisoft photoscan Pro using ~200 images for each model shot on a DSLR camera by Bobby Boessenecker. Units for 3d models are in Meters. Since a lot of 3D software is unit-less you may need to scale the mesh to get the correct size. Two file formats are supplied:

- PDF at lower mesh and texture resolution

- OBJ at high mesh and texture resolution in zipped folder

Skull, mandibles, and cervical vertebrae of Tokarahia kauaeroa (OU 22235)

Periotic of Tokarahia kauaeroa (OU 22235)

Bulla of Tokarahia kauaeroa (OU 22235)

Periotic of Tokarahia sp., cf. T. lophocephalus (OU 22081)

Bulla of Tokarahia sp., cf. T. lophocephalus (OU 22081)

These 3D Models are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. Acknowledge Geology Museum, University of Otago.

References

Boessenecker, R.W., and Fordyce, R.E. 2015. A new genus and species of eomysticetid (Cetacea: Mysticeti) and a reinterpretation of 'Mauicetus' lophocephalus Marples, 1956: transitional baleen whales from the upper Oligocene of New Zealand. Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society, doi: 10.1111/zoj.12297

- Introduction

- Otago History

- Reptiles

- Dolphins

- Sharks

- Whales

- Fossil penguins

-

Amphibians

-

Geological settings

- Vanished World Trail

- Geology Museum