Monday 8 January 2018 2:43pm

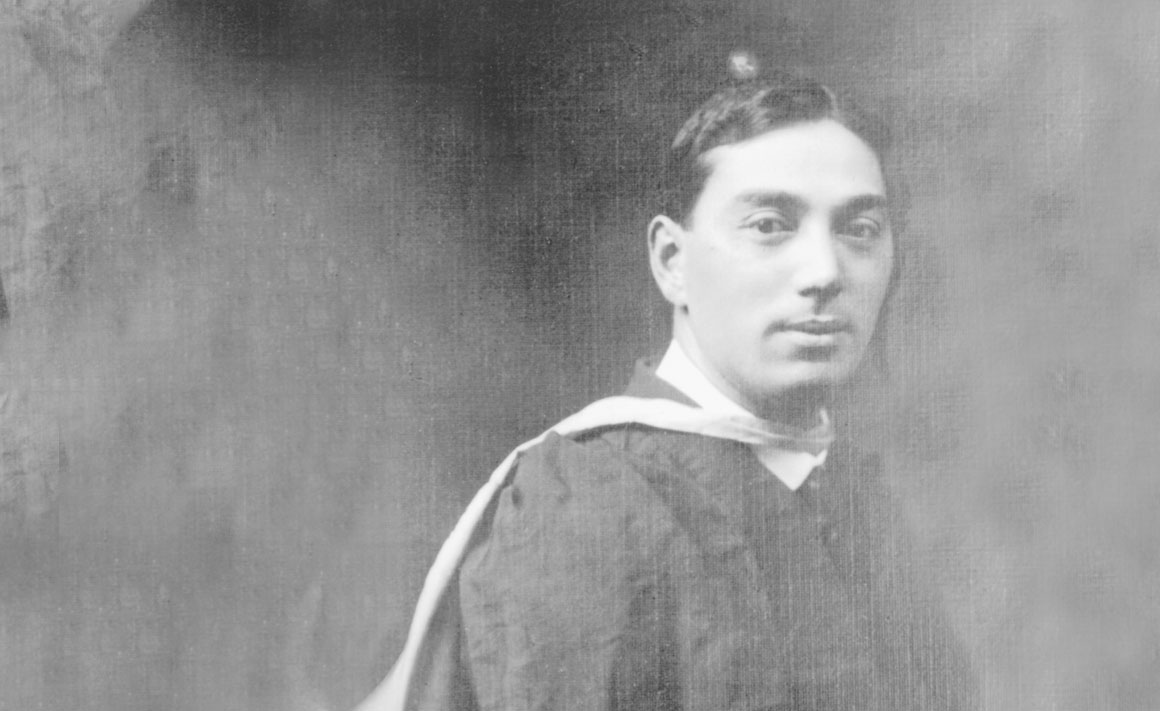

Monday 8 January 2018 2:43pmIn 1904 Te Rangi Hiroa – later Sir Peter Buck – became Otago's first Māori graduate and the first New Zealand-trained Māori medical doctor.

With an Irish father and Māori mother, Buck was raised with both Pākehā and Māori influences, and throughout his life embraced both as equally important.

He gained entry to Otago Medical School, graduating MB ChB in 1904 and MD in 1910, completing a thesis on “Medicine amongst the Māoris in ancient and modern times“, a subject that became a focus of his work. European diseases had devastated the Māori population: Buck realised that Māori had to adopt Western hygiene to survive. During a career in medicine, as a member of parliament and in the public service, he campaigned tirelessly to improve sanitation and health, and his work helped reduce the spread of epidemics and the death rate.

Anthropology was a long-held interest: he became a leading authority on Māori material culture and was something of a celebrity on the lecture circuit. Ultimately turning his skills to academia, Buck left New Zealand and undertook extensive field studies in the Pacific. Over subsequent years he was showered with accolades, including an Honorary Doctor Of Science degree from the University of Otago in 1937 and a Knighthood in 1946.

Te Rangi Hiroa was a man before his time, able to move freely and with dignity between the Māori and Pākehā worlds and working to bring them closer together. He remains an inspiration to this day.

Banner: Te Rangi Hiroa in academic robes, circa 1904. Ramsden Papers, Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand. Ref. No. F- 37931-1/2 -Today

1

The legacy of Dr Eru Pōmare

Whāia te iti kahurangi ki te tūohu koe me he maunga teitei

Seek the treasure you value most dearly: if you bow your head, let it be to a lofty mountain

This whakataukī encourages aiming high for what is truly valuable, with an underlying message of being persistent and not letting obstacles stop you from reaching your goal.

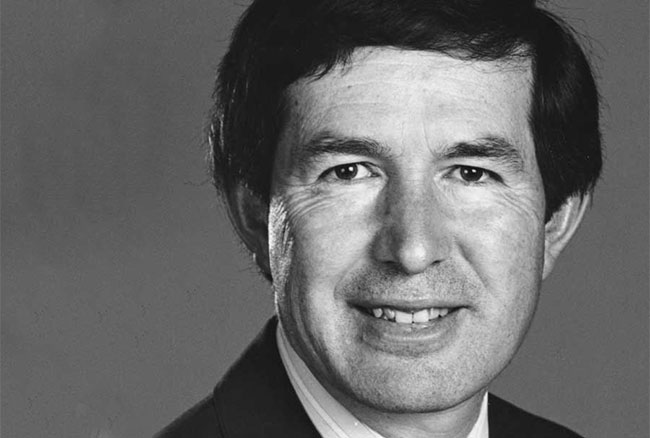

Otago alumnus Professor Eru Woodbine Pōmare did not let obstacles stop him from achieving significant improvements in Māori health.

“Eru was a gentle person, very committed and inspiring – a visionary and a strategic thinker,” says Associate Professor Bridget Robson (Ngāti Raukawa), from the University of Otago, Wellington. He broke through many barriers and was a trailblazer for Māori health and research.

“Much of our work is aimed towards changing the way health care and researchers work … to really make change, using kaupapa Māori and whānau ora approaches.“

Eru Pōmare (Ngāti Mutunga, Te Atiawa, Ngāti Toa, Ngāti Kahungunu, Rongomaiwahine, Rongowhakaata) had an impressive lineage and whakapapa. He was the grandson of Sir Maui Pōmare (Ngāti Mutunga, Ngāti Toa) who was the first Māori doctor (he trained in America) and gained prominence as a New Zealand Member of Parliament.

Eru was educated at Wanganui Collegiate and the University of Otago, and was a medical registrar at Wellington Hospital from 1967 to 1970. Supported by a Commonwealth Scholarship, he did postgraduate study in England and Canada. Between 1975 and 1986 he worked at the Wellington School of Medicine as senior lecturer in gastroenterology, then Professor of Medicine, and was appointed Dean of what is now the University of Otago, Wellington in 1992 – the first Māori to hold this position – while continuing to head Wellington Hospital's gastroenterology unit.

In July 1992, Pōmare established and led Te Pūmanawa Hauora ki te Whanganui-ā-Tara. When he died suddenly of a heart attack in his early fifties he had already achieved a huge amount for Māori health.

He wrote the New Zealand Medical Research Council special report on Māori health, establishing the Hauora: Māori Standards of Health series and, according to an obituary in the BMJ Gut journal, “in his unassuming, unaffected but scholarly and determined way, he set about trying to solve the dire health problems of his people. Eru Pōmare was well aware that Māori health problems not only required Māori solutions, but that doctors were only one of several agencies needed to improve the welfare of his people.”

His advocacy also encompassed awareness campaigns working with the Health Research Council, National Heart Foundation and the Maori Women's Welfare League.

Following Pōmare's untimely death in 1995, the centre was renamed Te Rōpū Rangahau Hauora a Eru Pōmare (the Eru Pōmare Māori Health Research Centre) to recognise his leadership. Papaarangi Reid (Te Rarawa) another prominent Māori health researcher, now Professor in Māori Health at the University of Auckland, became its director. The work they started continues today. Te Rōpū Rangahau Hauora a Eru Pōmare, now led by Associate Professor Bridget Robson, creates a kaupapa Māori space committed to improving Māori health outcomes and eliminating inequalities through quality science and ongoing theoretical development.

“We take a rights-based approach consistent with the Treaty of Waitangi and we engage with communities through a spectrum of influence from community development, policy advocacy, research dissemination and Māori health research workforce development,” says Robson, who is also Associate Dean, Māori at the Wellington campus.

Researchers focus on a range of aspects of Māori health and well-being, but also work to encourage and embrace kaupapa Māori methods as well as Māori tikanga across the campus.

A major focus is to improve inequities in health care and health outcomes, breaking down barriers, and exploring/resolving institutionalised racism in health. Projects include looking at multimorbidity and long-term conditions.

The researchers use and encourage more inclusive kaupapa Māori approaches to health research in order to reduce inequities in health. For example, the Te Ara Auahi Kore (TAKe) project works with other community groups to address Māori smoking rates, which remain high.

“Much of our work is aimed towards changing the way health care and researchers work – working more closely with communities, the DHBs and health providers, spending time with them to find what works for them, to really make change, using kaupapa Māori and whānau ora approaches, “ says Robson.

In recent years the team has compiled comprehensive Māori health profiles in District Health Board regions around New Zealand, focusing on essential data and evidence which other researchers, health providers and DHBs can use for decision-making, budgets and building plans and strategies. The profiles include indicators of whānau well-being, housing and income, health-service use and health status.

In 2015 these “snapshots” of Māori health in 20 DHB regions were translated by Piripi Walker and released in te reo Māori for the first time.

Commissioned by the Ministry of Health, the reports focus on the health status of Māori and reveal inequalities. Robson says that it's important to have this information in te reo Māori.

“The people and communities most affected must have the statistics in their own language. They help te reo speakers to engage with Māori health data and advocate for the issues affecting their communities,” she says.

Eru Pōmare set a high bar for others to follow in a sector that had been largely neglected before he applied his wisdom. His legacy continues today with Māori health researchers and students around the country following his approach. All agree there's much more work to be done, but by following in the footsteps of the quiet visionary, pushing boundaries and persisting, they hope to improve Māori health and reduce health inequities in Aotearoa.

Funding

Health Research Council

2

Te reo education

Tangiwai Rewi: “Now you can once again get an education in te reo Māori, but what a journey the language and our people have been on to get it to this point.”

Te Tumu senior lecturer Tangiwai Rewi has documented the journey of te reo Māori as an education tool in a recently released book, Te Kōparapara.

Co-written with her former colleague Matiu Ratima, their chapter begins with a history of te reo Māori, which pre-dates European settlement in the early 1800s, weaving its way through the journey of the language en route to its revitalisation in the 1980s.

“When the missionaries came, the religion and Christian-focused curriculum were taught through the medium of te reo Māori in 1816,” Rewi says.

“… children who attend immersion education are achieving well at the same rates, if not better, than their counterparts in mainstream education …”

“Tikanga and te reo were then absent in the curriculum for about 50 years if not longer and then, when it came back, it came back stronger than ever.

“Now you can once again get an education in te reo Māori, but what a journey the language and our people have been on to get it to this point. The significant difference, however, is that the education offerings are now defined by whānau with a view to realising their aspirations, their moemoeā, for their tamariki.”

The chapter discusses a raft of options available for Māori in education, with Rewi focusing on primary and secondary schooling. The work reads like a biographical analysis of her own 25-year career in the te reo Māori education sector and also offers examples of how different kura models have allowed whānau to flourish.

An uproar within the teaching sector over the introduction of Kura Hourua or partnership schools (charter schools) in 2014 saw Rewi seek out one of the new principals. She sought answers about why they had decided to pursue the new model.

“I could see from talking to them that it was making a positive difference for their community,” she says.

“I have highlighted that in this chapter, in particular, because nothing was happening in their community in terms of kaupapa Māori schooling options anyway.

“There was also nothing that I could see that was anything but success for their community by being involved and providing that option for them.”

While abolishing charter schools was a labour Party election policy, the 12 charters schools are transitioning to state integrated school status.

The successful revitalisation of te reo Māori continues, however one pattern remains stagnant: Māori families are still likely to put their children through mainstream centres and schools rather than the full immersion Te Kōhanga Reo (early childhood centres) and Kura Kaupapa Māori (primary through to secondary school).

The choices are available, Rewi says, but they are not always seized upon due to a number of variants, such as philosophical or logistical reasons.

“Maybe the current reinvigorated interest in te reo Māori will motivate change.

“But in my opinion, what hasn't changed is that children who attend immersion education are achieving well – at the same rates, if not better, than their counterparts in mainstream education. This is what the statistics are continuing to tell us as well.”

The book will be used to teach a number of classes: Rewi says the underlying message of te reo Māori and tikanga Māori education continuing to be an essential vehicle for educating students will serve as an important lesson for all of those who read it.

3

Paths to innovation

Professor Merata Kawharu, Dr Maria Amoamo, Dr Conor O'Kane and Dr Katharina Ruckstuhl: “Incorporating Māori knowledge into new products and services developed from science and technology research from the outset presents New Zealand with unique opportunities.”

University of Otago Business School Associate Dean Māori Dr Katharina Ruckstuhl is co-leading a Science Challenge project that could change the way we approach high-tech research.

One of 11 National Science Challenges, the Science for Technological Innovation Challenge (SfTI) is a multi-million dollar government investment in growing a high-tech New Zealand economy via the physical sciences and engineering. It includes projects such as 3D printing, robotics, “big data”, virtual reality and AI.

Building technical, human and relationship capacity is crucial to this challenge – technical capacity for bold and ambitious research, and human and relational capacity to ensure researchers work with industry and businesses so that science is not left “stranded in the lab”.

“We can use this insight to develop processes to help scientists, business and Māori break down barriers and enable engagement: the focus is on building innovation partnerships."

The science and innovation potential of Māori knowledge, resource and people are integrated into all the challenge's activity and its way of working.

The Building New Zealand's Innovation Capacity project, co-led by Ruckstuhl (Ngāi Tahu) and Associate Professor Urs Daellenbach from Victoria University of Wellington, runs the full 10-year lifetime of this challenge and is examining the human and relational capacities that drive people and networks.

The project has been observing more than 200 researchers across the challenge, documenting the diverse ways teams organise themselves to do science, how they connect with industry and Māori, and what makes a good innovation team.

"We know collaboration is crucial to innovation. We want to know how connections form and what a good relationship looks like. We can then use this insight to develop processes to help scientists, business and Māori break down barriers and enable engagement: the focus is on building innovation partnerships," Ruckstuhl said.

Working with her at Otago are Drs Diane Ruwhiu (Ngā Puhi) , Conor O'Kane and Maria Amoamo (Whakatōhea), all from the Department of Management; and Professor Merata Kawharu ( Ngā Puhi, Ngāti Whātua), from the Centre for Sustainability. They are observing the outcomes of some teams who started collaboration early, engaging with people they already knew, and other groups who have built in engagement during later phases and connected in new users once a shared interest or application of knowledge became evident.

Insights so far show leaders play a key role, and how teams relate with each other and their partners can determine how the science will unfold. Early interaction with industry and Māori groups is helping to inform key science choices within projects.

Research in the challenge has already sparked some innovations with promise for commercialisation. There are also new Māori-led projects to develop technologies for cultural connection with potential for commercial benefit.

Ruckstuhl says it's a very exciting space to be in. "It's looking at science delivery in a different way, where scientists bring their capability rather than their projects to the table for discussion. Research can then be co-constructed with business and Māori.

"The feedback we are getting is that there is demand for this type of approach, not only from the science system, but also from Māori and business who want innovative tech, but need pathways to engage. New processes for interaction will therefore be key.

"Active collaboration involves acknowledging that different perspectives can drive innovation. In particular, incorporating Māori knowledge into new products and services developed from science and technology research from the outset presents New Zealand with unique opportunities.

"A more collaborative approach will not only support the Science Challenge to tackle New Zealand's big high-tech issues, but I believe it will also help to shape overall science progress in this country."

Funding

Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment

4

Reframing indigenous research

Dr Ricky Bell: “Part of the process was trying to find commonality between the mātauranga that comes from Te Ao Māori and Te Ao Pākehā and how they conduct research.”

The old adage of good things taking time has proven true for the University of Otago's first Māori physiotherapy PhD graduate. Dr Ricky Bell's PhD officially started on 4 February 2014. He says the groundwork leading into that doctorate, however, started considerably earlier than that.

“My whānau identified early on that I was an academic young fulla. They started preparing me in ways that I did not even know at the time.”

After a successful clinical career in Brisbane, Bell (Ngāti Hine, Ngāpuhi, Ngāti Hau, Te Rarawa, Te Aupōuri) returned to Te Tai Tokerau in 2008. He opened a practice on the shore of Te One-roa-a-Tōhē (90 Mile Beach) and graduated with a postgraduate diploma in physiotherapy with distinction from the University of Otago in 2011 followed by a master's degree in manipulative physiotherapy in 2012.

This was to be the end of the academic road for Bell, however time spent with Ngāti Hine kaiwhaikōrero and kaumatua Edward “Pita” Kelly, affectionately known as Pā, helped Bell progress towards a PhD.

“Hapū whānau up here are really happy there's a new narrative out there that more closely relates to their lived experience of what obesity is and what the potential drivers are for it amongst our whānau.”

“Within your hapū, you have certain people picked to do certain things whether they like it or not. Some will do the diving, some the cooking, some the karanga: we all do our little bits to ensure our marae functions properly and strengthens the whole. I guess this PhD was part of my role amongst our hapū.”

Bell did not want to simply straddle Te Ao Māori and academia: he wanted to create a hybrid model infusing both worlds to find indigenous solutions to indigenous challenges.

“Part of the process was trying to find commonality between the mātauranga that comes from Te Ao Māori and Te Ao Pākehā and how they conduct research,” Bell says.

While the intention was to be mana enhancing, he was wary about the potential for negotiations between academic and mātauranga Māori to fall away. International academics also had criticisms about binary approaches to research.

However, he found inspiration in a 2005 paper by Ta Mason Durie that talked about an interface approach to binary work. “My interpretation of that paper is you can still maintain your own rangatiratanga by finding the commonality somewhere in the middle at the interface. You can use the strengths of each approach to go forward, rather than integrate them.”

With this newfound inspiration, and the guidance of Pā, and academic support from primary supervisor Associate Professor Steve Tumilty and whanaunga Dr Geoff Kira, all parties reached an agreement about a framework. After an 18-month journey, the PhD could finally begin.

Using his newfound framework, Bell created a “tangata whenua” narrative of what obesity was in Te Tai Tokerau. Factors such as colonisation, the subsequent intergenerational trauma, cultural revitalisation and collective health approaches were added to the traditional, but non-relatable, biomedical indicators of obesity in an indigenous context. He graduated in August 2018.

“Hapū whānau up here are really happy there's a new narrative out there that more closely relates to their lived experience of what obesity is and what the potential drivers are for it amongst our whānau.

“This isn't just in Aotearoa. I think it may have applicability internationally across other indigenous whānau.”

When it came to the marking of his thesis, there was a familiar name. Professor Meihana Durie, the son of Ta Mason Durie, describes the thesis as a groundbreaking PhD in physiotherapy.

“This dissertation offers a valuable and significant contribution to iwi-centred research and to Māori and indigenous health research in general,” Durie writes in his assessment of Bell's PhD.

“Huarahi Hauora is a body of work that fills a critical place and space around what constitutes Māori well-being from Māori worldviews. It is a dissertation … with the potential to make a significant contribution to health outcomes for Māori and, indeed, indigenous communities.”

As a resident in Te Tai Tokerau, Bell understands his work with Te Ao Māori is not over. In the meantime, he has been getting back to his big hobbies – diving for seafood and fishing.

“Towards the end of the PhD journey, the freezer was pretty empty with almost no kaimoana in there – it was starting to look pretty sad. Now we can make a start on addressing that.”

5

Community centre

Professor Michelle Thompson-Fawcett: “Undertaking research across disciplinary boundaries that examines and interweaves language, spiritual, social, justice, rights, histories and health, for example, is elemental.”

Dr Ricky Bell's community-centred framework is part of a growing trend by indigenous researchers to be more inclusive of indigenous groups. The frameworks involve a wider philosophy of using indigenous knowledge to shape research towards indigenous solutions, with academia as a vehicle rather than the destination.

For the Head of Department of Geography, Professor Michelle Thompson-Fawcett, indigenous community-oriented research has been a 30-year pursuit. She says there has been a considerable effort within recent years by indigenous scholars to decolonise and indigenise research.

“This type of research is tremendously important because it assists in the reclaiming by indigenous groups of research related to their own issues, such as self-determination and indigenous aspirations,” she says.

Thompson-Fawcett's work to acknowledge the importance of Māori and indigenous geographies saw her receive the 2018 Distinguished New Zealand Geographer Award and Medal. The award honoured her significant work nationally and internationally in Māori and indigenous geography, as well as iwi resource management and development.

For Thompson-Fawcett, who is of Ngāti Whātua descent, the honour is significant for community-centred research in general.

“This is not a neutral research activity,” she says. “It deliberately confronts structural power issues and actively seeks positive transformation.

“To have that openly applauded and sanctioned in the wider academy is hugely important.”

Thompson-Fawcett's community-centred philosophy extends beyond her research. In September 2018 she received an award for sustained excellence in the Kaupapa Māori category of the national Tertiary Teaching Excellence Awards.

She says Bell's work shows the importance of various academic strands adopting a complementary alternative to the status quo.

“Often conventional research and practice compartmentalise different aspects of our existence and experience. Working to disrupt the prevalence of such fragmentary research, while also prioritising and empowering the achievement of positive transformation, is key in this kind of approach.

“Undertaking research across disciplinary boundaries that examines and interweaves language, spiritual, social, justice, rights, histories and health, for example, is elemental.”