@Otago Issue 37

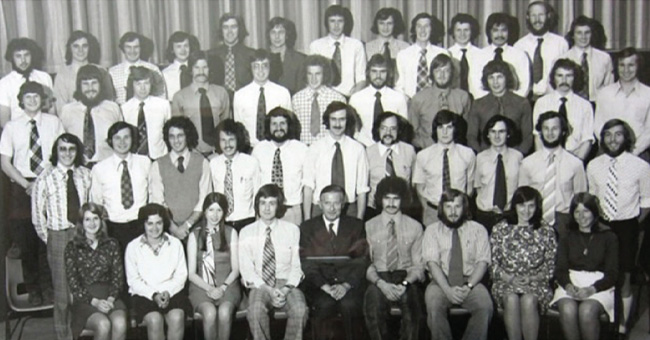

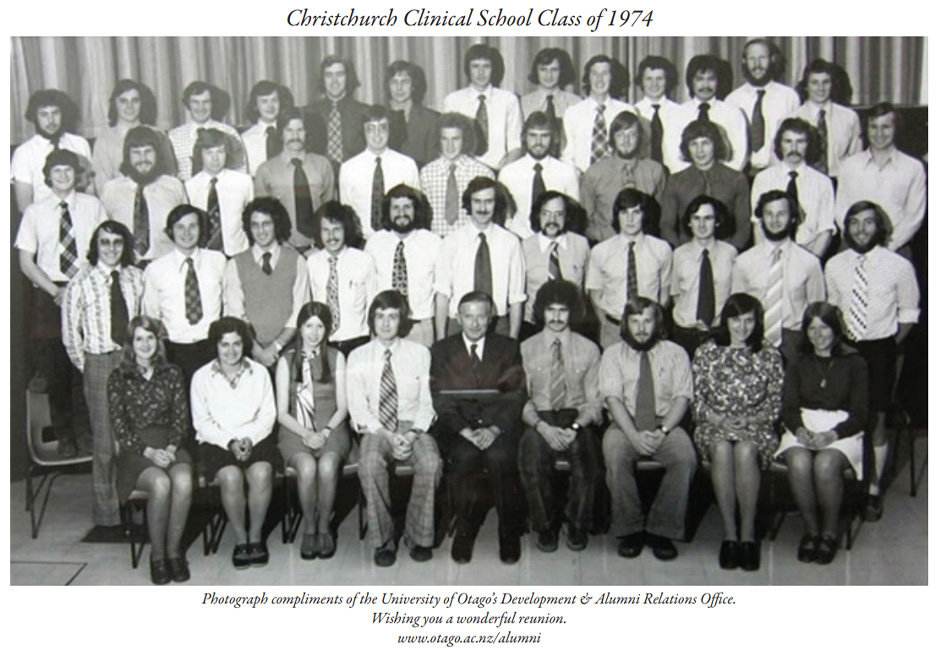

A special reunion in the Far North saw alumni converge from around Aotearoa New Zealand and Australia, to celebrate 50 years since their class became the first student intake at what was then the University of Otago’s Christchurch Clinical School.

Calling themselves the Class of ‘73 – in recognition of their unique place in the history of the Christchurch Clinical School, rather than the date they graduated – 26 classmates out of a possible 38 made their way north to Andrew Bowker’s home in Taipa, Doubtless Bay. With partners, 40 in total gathered for the reunion.

They were met at the gate of Andrew and his partner Gail Pearson’s long drive and handed lanyards featuring the original class mugshots taken on their first day of medical school, “just to remind them what they looked like. That was a source of great hilarity,” says Gail, who also studied medicine in Christchurch, graduating in 1983.

Most came by car, one by campervan and another flew his own light aircraft from Nelson. Three flew in from Australia.

“It was fantastic,” says Andrew. “One came down from Cairns where he’s had his working life as a radiologist, and he said ‘Andrew, I think it’s the best thing I’ve ever been to’.”

In preparation, Andrew had asked everyone to write 100 words about their work, where they lived and their family, “so that none of that small talk had to be done when they arrived”.

On the first evening, they assembled on logs and folding chairs on the beach at the bottom of the property and, following a greeting from Andrew, remembered the five classmates who had passed away. After tributes from friends and a chance for everyone to speak, Andrew’s friend, Kaumatua Keni Piahana, offered a Māori perspective to the remembrance, and a blessing.

The next day started with a BBQ brunch, then the group gathered for a series of mainly non-medical talks from classmates. Topics were as diverse as woodturning and how trees communicate, to how to deal with family heirlooms, working life as a GP in Inglewood, eco-friendly homes and politics at the University of Otago.

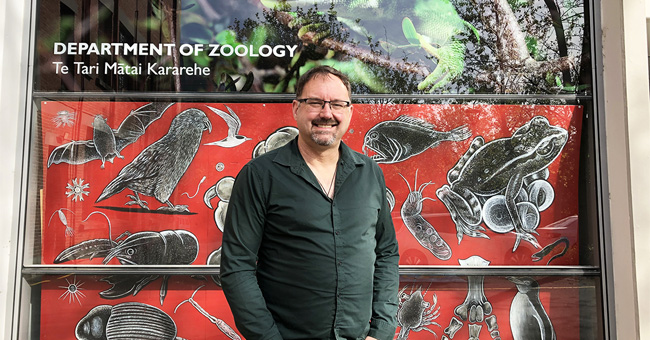

Keynote speaker was John Sumich, a GP and longtime conservationist from West Auckland, who established Ark in the Park in the Waitākere Ranges and the adjacent Habitat te Henga. After more talks, including one on astronomy, the day was wrapped up with a celebratory dinner.

Describing the class as a “tight knit group” Andrew says they actually didn’t talk a lot about the early days, because many had formed life-long friendships in the class and had kept up with each other over the years. They had met twice for reunions previously, on their 10th and 20th anniversaries.

“You worked together, you did long hours, you socialised together, you went through traumas and first medical experiences together; it was a mutual support club. When you have that as a base you don’t need to go back to small talk because you’ve forged a very strong relationship,” says Gail.

As well as being the first clinical class in Christchurch, they were unusual in that the class was a self-selected group, with 44 students out of 126 voluntarily choosing to study in Christchurch. In following years, classes were split evenly between Christchurch and Dunedin, and then Christchurch, Dunedin and Wellington.

“So we were kind of a select group, and I think we had a group of people who were prepared to give things a go as part of that. Of course, some were Christchurch folk who just couldn’t wait to get back to Christchurch,” says Andrew, who hails from Gisborne.

Many in the class also played rugby together, on a doctors’ team for the Christchurch Rugby Club. “It was always a bit of trouble getting a quorum. You’d have a Saturday morning ward round which would often drag on and on the field we’d have nine people, you could start a game with nine. By about the end of the first 10 minutes we’d have most of the 15 on the field, with a few more getting changed on the sideline.”

In those first years the medical side of their training at Christchurch was particularly strong. The new students knew the staff would be “trying their hardest”.

“And try their hardest they did, they were great. George Rolleston was Dean and he was a good figurehead. Our class performed particularly well; as a measure of success, which is debated by some of our GP colleagues, there were an awful lot of specialists in our group.”

The Christchurch class of ’73, which included only five women, went on to work as general practitioners, in pain management, drug and alcohol addiction, as respiratory physicians, paediatricians, ENT surgeons, anaesthetists, general, vascular and orthopaedic surgeons, in obstetrics and gynaecology, neurology, radiology, cardiology, gastroenterology and psychiatry.

Amongst their cohort they counted a Rhodes Scholar, haematologist Derek Hart, who died in 2018. He was the first person to identify the role of human dendritic cells as critical effectors in immune rejection. Many of the class were at the forefront of medical technology making its appearance in the 70s and 80s, including radiation oncologist Associate Professor Chris Atkinson, radiologist Tony Young and Andrew with laparoscopic surgery after he returned to New Zealand from Australia in the early 90s. GP Adrian Gray ran one of Sir Edmund Hillary’s hospitals in the Solukhumbu region of Nepal.

“All have a claim to fame in different ways. I think John Mercer was the first non-Christ’s College old boy appointed to the clinical staff in Christchurch,” says Andrew.

Gail says a lot of the class were, “forerunners, creating departments, creating innovative techniques, whether that be in surgery or medicine.”

“Every single one has a very interesting story. They’ve been creative in what they’ve done, Pete Manson with his ICU unit in Tairawhiti, John Sumich with his conservation, Diane Jones working with Māori as a liaison person – a pākehā female doctor working in a Māori culture was unusual.”

Most have now retired, with Andrew about to finish practising at the end of this year.

As everyone headed home, Andrew and Gail say people were realising that those friendships they made in their twenties, were actually quite deep, or, as Andrew put it, “I realised quite a lot of them who weren’t particular friends in clinical school, are actually close friends.”

Andrew and Gail have asked classmates to expand on their 100-word introductions and there are plans for a class book in the near future. Many who attended have asked for another reunion in five years.

“It was so cohesive. You can tell when you’ve had a good function, because nobody wants to leave.”

Kōrero by Margie Clark, Communications Adviser, Development and Alumni Office