@Otago Issue 37

*Since this story was first published, Nicola has been on our screens again and in international media discussing the raucous, and now globally-famous, Bird of the Century competition.

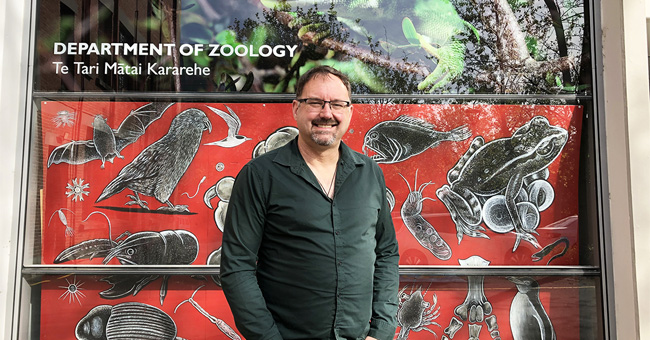

The interview has run over time, the chair of the board is trying to get in touch, but Nicola Toki confesses she could keep talking about Aotearoa’s wildlife and natural world all day, every day.

Luckily, it’s exactly what the Chief Executive of Forest and Bird, co-host of TVNZ series Endangered Species Aotearoa, and Otago alumna actually does for a living.

And even on Zoom, without the cheeky banter with fellow TV host Pax Assadi and encounters with the real stars of the show – the extraordinary wildlife living on our shores and a wonderful collection of Department of Conservation rangers quietly going about their work – Nicola’s enthusiasm is infectious.

“We are getting some quite incredible feedback,” she says. “I’ve been overwhelmed by how much people love it.”

Nicola volunteers that right from childhood she wanted to be David Attenborough. Although she admits she wouldn’t be able to be as proper as Attenborough, as she enjoys “a bit of whimsy and quirk”.

“I couldn’t dream of having the gravitas of David Attenborough describing moss growing on a log, which I could listen to for hours.”

She says the joy of co-hosting the show with Pax is that he is seeing it all for the first time, so viewers get to see what he sees, through his eyes. It’s the type of wildlife show she’s wanted to see on our screens for years.

“One of my personal bugbears is that sometimes us nature people – conservationists, environmentalists – we don’t do ourselves any favours. We start talking about nature and it’s very earnest, it’s very worthy. We use lots of really long and complex words which bore the crap out of everyone. And sometimes nature is funny.”

Setting the tone for the series was simply a matter of being themselves. “Pax said I don’t need to be hamming up being the fish out of water, a city boy stuck in nature, because I will be. And [for me] the reality is I’m a middle-aged, busy working mum with lots on the go and I just want to be who I am.”

Telling nature stories goes a long way back for Nicola, but she says she’s only recently felt confident enough to call herself a storyteller. “This is not something you put on your business card.”

It is however something that is behind her positivity and optimism, even in the light of the grim statistics about many of our species.

“I feel like when you’re telling stories about nature in New Zealand, you are walking a tightrope of hope.”

She says people need to understand that there’s something at stake or they won’t engage. “They’ve got nothing to grab. This is what I learned in my very first day at my Natural History Filmmaking diploma – it was about the art of storytelling, and that’s very much about how you have to have something at stake.”

However, the flipside is not wanting to make people feel helpless or depressed.

“But what I think you see in the programme and what I know, is that if you have hope, that drives action. And what I want people to understand and see is that all over the country we are meeting people taking action to turn things around, and that all is not lost.”

She describes how when she visited the Chatham Islands, she picked up a little Black Robin trinket, which she carries everywhere. “It’s a constant reminder that you can be down to the worst situation – one viable female, the Old Blue that I sat and watched in my living room on those Wild South episodes many years ago. And those people involved just never gave up.

“I think that’s such a strong message, and we have so many success stories around New Zealand, with our predator free islands and the work that we’ve been able to do bringing species back from the brink. That’s a great beacon of hope for us to be able to look around and say, well what else can we do?”

It started in her nana’s backyard

Nicola can trace the path to her current position at Forest and Bird right back to her nana’s backyard. She and her brother Tony would spend lots of time tearing around the bush block up the back of her nana’s farm near Tokanui in the Catlins.

At the time, she says many farmers in the region were changing from traditional sheep and hill country farming, to planting hardwoods, which meant cutting down bush. “My nana just absolutely would not allow that on her farm, and when she sold it she made sure the bush was protected. I don’t think she was a conservationist necessarily, but she just loved the bush and considered it part of her place.”

Nicola remembers seeing the heavy machinery going down the road and cutting down the bush on the neighbouring farms. “And that must have resonated.”

Later in her childhood, her family moved from Southland to Mount Cook village, right in the middle of Aoraki/Mount Cook National Park. “As a kid you’re not necessarily thinking about environmental principles or anything like that, but certainly being in that landscape and being embedded in that place and being able to experience that wildlife kind of sticks with you.”

She was forever bringing home living things, like tadpoles, and her mum would often find stray creatures under the couch or in the sugar bowl.

“I just have always had a love for the natural world. I didn’t know what I wanted to be necessarily, but I knew that that was the thing that spun my wheels.”

During teenage years in Rangiora, Nicola spent summers at science school at the University of Auckland while her friends were going to festivals. In the end she chose Otago because she knew there was a good Zoology department, and she just really liked the buildings.

With a few papers to spare after signing up for all the required science classes, her parents suggested that as she was really good at arguing why didn’t she try Law?

She did, then got into second year Law, and decided she’d just keep on going. She got right to her final year when doing both Law and honours Zoology proved too much.

“I loved both faculties. It just got very difficult to fit it all in . . . I remember bursting into the law lecture theatre a bit late because I’d been at a freshwater field trip and there I was in my cargo pants and gummies.”

And at the end of the day, what she really wanted to do was study penguins in Antarctica. After pestering her Zoology honour's supervisor, eventually she was given the opportunity to join the Chilean Antarctic Institute on their summer fieldwork.

“I spent a very happy six weeks in a one room hut with two Chileans and an English guy . . . up to my ears in penguins all day long. It was my first real fieldwork and first real glimpse of nature ‘tooth and claw’, and it was mind blowing.”

She realised however that while she might know a lot about penguin chick moult, “I don’t know if that’s going to move and shake people in terms of getting them to love nature as much as I do. And I guess that was the driver – I love this stuff, how do you get other people to love this stuff?”

Back at Otago, she joined the first cohort of the Natural History Filmmaking and Communication postgraduate diploma, established in collaboration with the Natural History Unit. “All of a sudden the people that made the films that I was obsessed with as a kid were my lecturers, I loved that.”

Camera operator to Chief Executive

Her first job however was not on a windswept isle filming rare wildlife, but as a camera oper ator at Channel 9 TV in Dunedin.

ator at Channel 9 TV in Dunedin.

“We basically ran on bare bones, you were a camera operator, floor manager, director in the studio, soundie…”

In the years since, the experience has helped her work with television crews, just as her law studies have allowed her to have good conversations with legal teams.

A stint selling ads at the Otago Daily Times also gave her skills she still values, in terms of engaging with people and maintaining a client relationship.

“It’s always amusing to me how the things we fall into, that we think of as the wrong things, often are the things that give us the step to the next thing.”

The next thing for Nicola was a job in a media and public awareness role for the DOC Otago Conservancy office.

“I just couldn't believe that. I think three weeks into the job I got a call to say that there'd been a Southern Right whale sighting near Karitane. And could I race out there with the ranger, and we jumped in a local fishermen's boat. And we're on. I spent an afternoon hanging off the front of the boat taking photos of a Right whale. And I was just like, people are paying me to do this.”

This led to the role of strategic media adviser in head office, where she tried to focus on proactive stories about DOC’s work – resulting in a weekly appearance on What’s Up DOC on the Good Morning TV show, and researching, writing and presenting 200 episodes of Meet the Locals, four-minute mini-documentaries about Aotearoa’s wildlife and wild places.

Then two things happened. Firstly, the government decided it wanted to mine in National Parks. “As a kid who grew up in a National Park, I was not cool with it. I felt very uncomfortable being a spokesperson for the department.”

Secondly, Forest and Bird rang and said come and work for us. So, Nicola moved back to the South Island and took up a national advocacy role. This was followed by positions at Ospri in pest control education and advocacy, and Fonterra, managing the Living Water Project in the South Island, in partnership with Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu, to improve freshwater quality.

Then came whispers about a job she could only have dreamed of – the Minister for Conservation was looking for a Threatened Species Ambassador. “And I just was like ‘oh my God, that's my job, I need to have that job’.”

“It was very inspiring, being able to go out and meet people who are doing incredible things for nature. Actually, that's been a privilege of almost every part of my role, whatever role I've had.”

Wanting to expand her leadership experience, she then took on the role as DOC Acting Science Manager, followed by DOC Director of Operations for Eastern South Island. She was appointed Chief Executive of Forest and Bird in April last year, a role which brings together all areas of her experience.

And she felt the timing was right.

“I genuinely believe that right now New Zealand is having this once-in-a-generation conversation with itself about who we are. And you can tell because we've got this angst about Te Tiriti and with co-governance and we don't know how we feel about that.

“It's like we just woke up yesterday and went ‘oh my God, it's not 1955 anymore. And if we're not rugby, racing and beer, then who the hell are we?’”

With society also facing a biodiversity and climate crisis, Nicola says she knew Forest and Bird, as the voice of nature in New Zealand for 100 years, had to be at the table for that conversation. She sees her role as looking to the next 100 years, making sure the organisation “represents all of New Zealand and is relevant and current”.

Personally, she finds huge satisfaction in “getting out of bed every morning and doing something good”.

“When I was working for the department, I felt the responsibility of spending taxpayer money very, very heavily. And when I was working for Fonterra, the same for shareholder money. However, I think when you're working for a not-for-profit and you know that everything is paid for by hard working New Zealanders, who took money out of their pocket for you to do this work, it’s an enormous responsibility and privilege, and is something that makes me really proud. And a little bit nervous sometimes.”