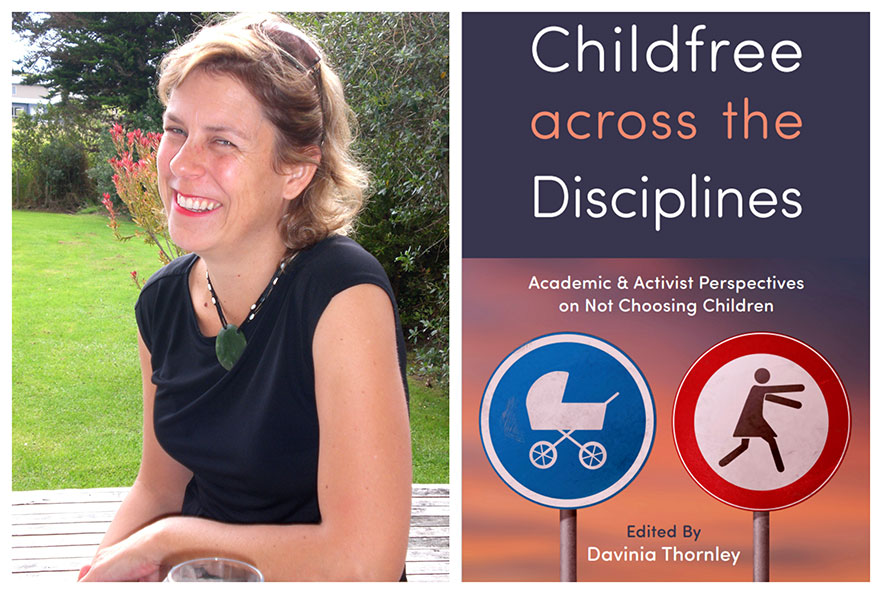

Ahead of its launch by Rutgers University Press on 15 April, editor Dr Davinia Thornley (Te Tari Papaho - Media, Film and Communication) discusses how Childfree across the Disciplines: Academic and Activist Perspectives on Not Choosing Children seeks to move perceptions of those who choose to not have children beyond sweeping generalisations.

"Although it may strike the reader as verging on facetious to point this out so blatantly—childfree people are simply people. Sometimes they overachieve, sometimes they're slackers: most of the time, they're somewhere in-between. Just like parents and those who want children."

What is it about?

Childfree across the Disciplines: Academic and Activist Perspectives on Not Choosing Children focuses on the relationship between childfreedom, social ideologies, and community activism. The authors ask (and frequently answer) the question: how do childfree people negotiate their subjectivity in a changing demographic, economic, media-saturated cultural landscape.

Why did you undertake this research, and the publication project?

Recently, childfree people have been foregrounded in mainstream media. More than 7% of Western women choose to remain childfree and this figure is increasing. Being childfree challenges the 'procreation imperative' residing at the center of our hetero-normative understandings, occupying an uneasy position in relation to—simultaneously—traditional academic ideologies and prevalent social norms. After all, as contributor Adi Avivi recognizes, “if a woman is not a mother, the patriarchal social order is in danger.”

This collection engages with these (mis)perceptions about childfree people: in media representations, demographics, historical documents, and both psychological and philosophical models. Foundational pieces from established experts on the childfree choice, alongside both activist manifestos and original scholarly work, are comprehensively brought together.

Academics and activists in various disciplines and movements also riff on the childfree life: its implications, its challenges, its conversations, and its agency—all in relation to its inevitability in the 21st century. Childfree across the Disciplines unequivocally takes a stance supporting the subversive potential of the childfree choice, allowing readers to understand childfreedom as a sense of continuing potential in who—or what—a person can become.

You should read this book if . . .

You have children or want children. You should read it if you are childfree! And you should read it if you're not sure where you sit. Given that childfreedom has only just become a recognised category (as distinct from childlessness or infertility), many people are unclear about what it means to be childfree and why people choose to make this decision. This book provides one place to hear from those who have made this choice. Through these essays, I hope readers begin to glimpse that not only is it eminently possible to be childfree and fulfilled, but also that childfreedom for some people may prove one of our most valid and sustainable ways of life as we collectively face an uncertain future.

I hope this book makes people think about . . .

Somewhat personally for me, it's important to recognise and 'out' a subtle but damaging assumption about childfree people: that they are more committed to their communities, their jobs, other people. Received wisdom suggests they should be, at least—as though to somehow counter their 'lack'? This divide and conquer approach benefits no one and continues to pit parents against non-parents in unhealthy and unproductive ways. Until everyone is free to make the reproductive decisions appropriate for their lives, no one is: further, it is important to extend that understanding to other aspects of everyday life.

Although it may strike the reader as verging on facetious to point this out so blatantly—childfree people are simply people. Sometimes they overachieve, sometimes they're slackers: most of the time, they're somewhere in-between. Just like parents and those who want children. As Amy Blackstone suggests, “by noticing the flaws in sweeping generalizations, understanding our commonalities, pushing for better work-life balance policies for all, and letting go of the name-calling” (82), we can begin to recognise the common humanity we share. We can make space for choice and growth in all of us, most especially when our choices differ.

In addition to contribution from Dr Thornley, the book features contributions from Berenice Fisher, Melanie Brewster, Olivia Snow, Adi Avivi, Amanda Michiko Shigihara, Christopher Clausen, Laura Carroll, Natalia Cherjovsky, Rhonny Dam, Laura S. Scott, Erika M. Arias, Laurie Lisle, Anna Gotlib. Read more on RUP here.