@Otago Issue 40

Kōrero with Te Papa curators Katie Cooper and Rebecca Rice

In conversation with Dr Katie Cooper, Curator New Zealand Histories and Cultures, and Dr Rebecca Rice, Curator Historical New Zealand Art, two alumnae, who talk about their very different paths from Otago to Te Papa Tongarewa Museum of New Zealand.

Dr Katie Cooper (left) and Dr Rebecca Rice (right) at Te Papa.

Dr Katie Cooper.

What drew you to Otago, to study History and Physiotherapy?

What drew you to Otago, to study History and Physiotherapy?

Katie: I grew up in Gore and was always a bit of a home girl, so I didn’t want to go too far. My mum, who is a history teacher, also went to Otago and my older brother had been as well, so we had that family tradition. I did my four years of undergrad and then I worked for a year at Otago Museum. I came back to Otago full time to do my PhD. I valued and loved my time there.

Rebecca: I had a slightly different journey! I was born in Oamaru and moved to Dunedin in my fifth form, attending Otago Girls’ High School. My mother and my uncle are also Otago graduates, so we were a Dunedin family really.

I guess I’m someone that always held the arts and sciences in tandem. At that certain crunch point where you’re figuring out what to do, I was doing a lot of singing, dance and drama, and physio felt like a place where I could pursue a path that reflected my interest in movement and the body.

I made a lot of wonderful friends that I have absolutely kept for life through that degree.

Rebecca Rice.

What are some of the most important things you took away from your degree?

What are some of the most important things you took away from your degree?

Rebecca: I’ve been researching 19th century botanical women artists over the last few years and recently met a woman who is a botanical artist, who was also a lecturer at the Physio School. She said: ‘But Rebecca, don’t you think there’s something about those observation skills that we drill you on in physiotherapy and the way you learn to look at art works?’ I thought: ‘You’re right’.

Physio is also a practice that is about relationships, and a lot of our work here is about relationships, whether it’s about collaborating curatorially, or engaging with people on sensitive issues. Those communication skills are fundamental to physio, so I would say that is the main thing that I’ve carried from that career through my various roles.

The other thing that I hold onto about Otago University is their art collection. There were good days and bad days at university, but one of my favourite places was to go and hang out with Ralph Hotere’s Rain (1979), displayed at the time in the original Hocken Library building. That was amazing, that power of having art on campus was really important.

Katie: As a postgraduate student, of course you develop research and writing skills, but some of the other jobs I did like tutoring and research assistant work where I was pulling together images and copyright permissions, those have been so helpful in this job.

I think I was just so lucky, the teachers I had were wonderful, the History department was so supportive, and I never felt any kind of gatekeeping. I’d love to give a shout out to my supervisors Angela Wanhalla and Mark Seymour. They were, and continue to be, incredibly kind and insightful mentors. (Katie’s PhD thesis on the Rural New Zealand Kitchen is due to be published later in the year.)

Dr Katie Cooper and Dr Rebecca Rice at Te Papa.

Rebecca: How did you leap from physiotherapy to art history?

Rebecca: How did you leap from physiotherapy to art history?

It kind of grew. My mother studied Botany at Otago and she was the scientist in the family. My father, even though he worked in the traffic and road safety industry, was the artist, the constant doodler. So, I had these oscillating things in my DNA.

Physio wasn’t where I wanted to be for the rest of my life. I went back to Vic [Victoria University of Wellington Te Herenga Waka]. I thought I wanted to do music but ended up falling in love with art history.

I’ve worked a lot on the relationship between art and science in my curatorial research – I don’t see them as two binary opposites.

How did you both find your way to Te Papa?

How did you both find your way to Te Papa?

Rebecca: I had a very long academic journey! I spent a few years when I arrived in Wellington working as a physiotherapist and then went back to uni. Alongside that, I was doing all the art history tutoring and teaching jobs, working at art galleries, while still doing the physiotherapy gig at Wakefield Hospital. In 2011 the opportunity to work at Te Papa came up, and in 2012 I was appointed to the position I still hold.

Katie: This is going to sound so obnoxious because I was interviewing for this job as I finished my PhD, which is so lucky. I just know that is not the reality for most people. I wasn’t sure what I was going to do once I’d finished my thesis, I was just looking to that finish line and then I would figure it out. But this job came up and it sounded wonderful, it sounded like just what I was looking for because it does have that mix of academic research and public engagement.

A couple of days after I handed in my PhD, I flew up to meet the team and do the final interview. I was very nervous because I thought: ‘What if I don’t pass, what if I don’t get my PhD? Then I’m going to lose my PhD and the job!’ Thankfully it all worked out.

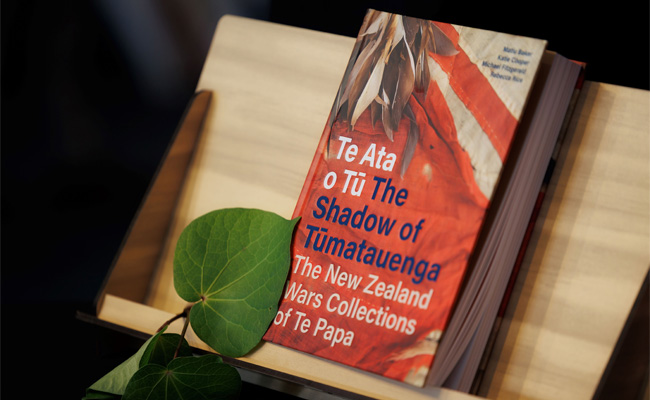

Te Ata o Tū, edited by Otago alumnae Dr Katie Cooper and Dr Rebecca Rice, with Matiu Baker and Michael Fitzgerald.

What does a curator do?

What does a curator do?

Katie: It’s different every day. Every day a question will be put to you by the public which is always really interesting. Obviously, we do have our specialties, but you need to be able to do a range of different things.

My first project when I got here was to redo the label for the Britten motorcycle, and despite my rural upbringing, I didn’t know anything about motorcycles! So that was a bit of a crash course. Then you’ll get an enquiry about a war medal, or you’ll need to write something about a cannon, so you’re always learning.

Our job is both to research and share stories of the objects in the collection but also to build the collection through acquisitions. We get offered things almost every day by members of the public who are looking for homes for their precious objects, or we go out and look at things proactively.

Rebecca: The way we engage with the public is across multiple formats. You’ve got your more popular end of things – blogs or exhibitions where you’re really trying to reach a broad generalist audience – and then we’re still maintaining our academic credentials so continuing to publish in those contexts is important.

You co-authored the recently published Te Ata o Tū The Shadow of Tūmatauenga: The New Zealand Wars Collections of Te Papa. Can you tell us how the book came about?

You co-authored the recently published Te Ata o Tū The Shadow of Tūmatauenga: The New Zealand Wars Collections of Te Papa. Can you tell us how the book came about?

Rebecca: I have been interested in the visual culture associated with the New Zealand Wars since my honours year, when I looked at a small collection of watercolour drawings of Māori flags that were brought together by an amateur historian who was also a draughtsman and artist.

In 2017, the Government announced the dedication of a day to remember the New Zealand Wars. I’d been working a lot with my colleague Matiu Baker, Curator Mātauranga Māori, and we got the go ahead to pull together a small exhibition to coincide with that first Rā Maumahara. Then Te Papa Press became interested. We were really conscious that day had been inaugurated to recognise the importance of that particular period of history and to address its absence from our landscapes, from our curriculum, from our social memories. This book represents the first step towards addressing the silences in Te Papa’s own collections and histories.

Why focus on objects?

Why focus on objects?

Rebecca: Matiu and I argued away from a text heavy book to something that was much more visually driven, because we wanted it to be interesting and useful to a general and education audience. We’re in this business because we believe in the power of taonga, artworks and objects to open up stories. I think when you’re dealing with really difficult histories, having something that mediates the conversation, that offers up different perspectives about the people, the places, or events, is incredibly powerful.

Katie: We’ve had such rich conversations, with the objects as a starting point. They have such complicated, tangled histories. And they also take you right there to that moment; these are the weapons of war, these are the trophies of war, these are the reflections of war. There’s an immediacy to the objects that I think gives the book a particular poignancy.

One of the major challenges to us was to bring more life and personality to the stories because of the nature of the topic and the nature of some of these objects. Descendants encouraged us to think about the person’s whole life and to bring a bit more of that to the book to give it a little bit more heart, which was wonderful. We felt so privileged to be gifted those reminiscences and to have those conversations.

Rebecca: There were people that said this was the first time they’d been asked to share their kōrero about their tipuna, which in some instances was quite shocking, given the scholarship that exists around some of these people.

It’s not to say we’ve done it perfectly – this is just the beginning of us as an institution trying to reckon with those objects, with our collections. Because we are a colonial museum, most of our collections were built through the lens of the pākehā collector, usually male, and were often acquired through dubious circumstances.

Which of the objects are most powerful to you?

Which of the objects are most powerful to you?

Katie: It’s so hard to pick because all the objects have amazing stories. We’ve been researching the collection for quite a long time now, but we saw the power of the objects all over again on the day of the launch. We had the pōwhiri, the launch, the blessing and then we had a session in the storeroom where attendees could come and see the taonga.

To see people interacting with those taonga in that space, with song and such rich conversation, that has really given me a new perspective on those objects. We hope the book is just the first step in a lot of work that we as an institution need to do, building on those relationships.

Rebecca: I’m really pleased that we included taonga from artists, activists, photographers and makers working right up to the present moment. These works reflect our histories in different ways, reminding us of the ongoing relevance and legacies of the New Zealand Wars in our contemporary moment.