Outgoing Landfall editor Emma Neale talks about what treasures we can expect to find in Landfall 241, out now.

Landfall 241 – what are you most excited about?

Landfall 241 – what are you most excited about?

It's so hard to choose – I'm hyper about all of it. This issue has great fiction from Amber Moffat, who also writes for children; with her story and a short script from Victor Rodger, we're publishing two horror genre works that tackle complex and urgent themes yet do so with different flavours of humour. These two works look at, among other things, women's relationship to their bodies, pregnancy; and our treatment of essential workers, the way we often overlook older women – with comedy and a usefully 'creepy' tension that gets the reader questioning cliches and assumptions about beauty, motherhood, power, wisdom, service, class, and cultural background.

I love the variety of poetry that we have this issue, which starts with song-like, whimsical and thoughtful poems from Bill Manhire – a coup for me, I feel, for what will my final issue, as Bill was most certainly the most significant teacher I had as a novice writer in my 20s. The shorter poetic works, like the tightly structured, heart-cramping piece from Joanna Preston, are complemented by wry, humourous, quirky and yet socially astute flash fiction from writers like Lyndsey Knight and Zoë Meager.

I also have to carol and shout about a memoir/creative non fiction piece by Sarah Lawrence that felt to me as if it could become a canonised classic of childhood recalled – Frameian in its non sentimental yet sensuous celebration of childhood, and its language also recalls the glee of children's picture book authors like Valeri Gorbachov. I loved it so much I sent it to my mother (adult novelist and children's writer Barbara Else) before OUP had even told the author she'd been accepted; I couldn't contain my excitement.

Caoimhe McKeogh's story also explores the childlike, but this time, in an adult man not entirely up to crucial new responsibilities, and as it gently unrolls his waywardness the subtle touches of his eccentricity are all the more destabilising and affecting: both Sarah and Caiomhe are younger writers to watch closely, I think.

We, have, too, a clear-eyed, frank essay on unconscious bias and racism from Anton Blank: the kind of submission that makes an editor sit up and think, damn it, I wish I'd had a rich fund to commission work like this and hallelujah that it's come through unsolicited. Ngā mihi nui, Anton, for sharing your mother's and your own hard-won, long-wrought wisdom with readers.

This edition will include the winner of the Charles Brasch Young Writers Essay Competition. Why is it important to have competitions like this?

It's so important to encourage young writers to aim for a high standard, and to help them know that their opinions matter and are heard. It encourages them to be informed; to organise their arguments; to see writing as a tool of great value. The competition encourages the most talented writers to see worth in their skills, and, I hope, go on to apply them to all kinds of professional contexts: from the literary, to journalism, to advocacy roles, to careers in the law, science communication, politics, social justice, you name it. A well-researched and well-written argument or discussion is something that has power in a huge variety of contexts.

Overall, this year, I did feel that the essays lacked a certain energy or creative flair: it's so fascinating that different years do have different characteristics as a whole. But as I say in my report, if young writers read the winning essays across a number of years, they will get a strong sense of just how flexible the essay genre is. This year we have a somber, pared back argument about NZ's approach to the climate crisis; last year we had a hauntingly poetic memoir of anorexia. You can write about anything and knock an editor's spectacles off if the language is used with conviction, precision, wisdom, research, poetry, and flair.

Can you tell us a bit about the featured artists?

I'm delighted that we have a photographic series from Bridget Reweti, which I find joyously hallucinatory. The page opens up like a portal, as her double images blend into a deep sense of space and place, as if, by looking at the page, you are transported directly into the natural world she photographs. It gives the viewer an almost 'trippy' sense of arrival, of landfall, and yet there is a haunting sensation to this, too: as if we travel there in spirit; as if we are already our own ghosts…the 3 D effect is perhaps all the more powerful in a world where extensive travel has become so reduced. Yet the title of the series, 'Known Seas' also reminds us of the damages of the imperial mission, as it reminds us that Aotearoa had a known, storied oral tradition well before 1642 (Tasman's arrival as meditated on in Curnow's poem, 'Landfall in Unknown Seas'.) I can't help thinking too that the fact that here we have two images combining into a single view that there might be a visual reference to biculturalism; these are the kinds of philosophical ideas that seem to quietly move within the suspended space of the photographs.

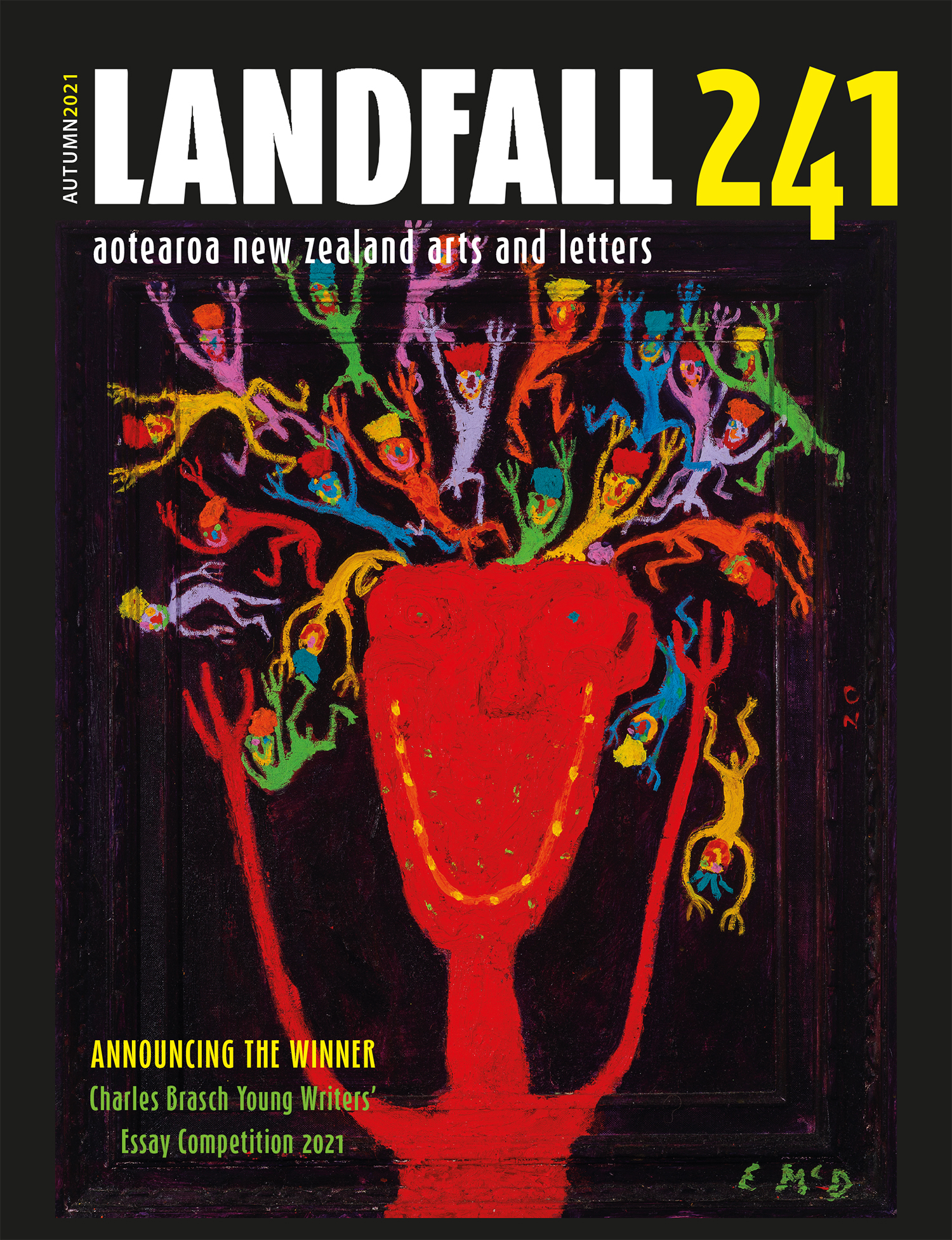

I'm also thrilled that I had a chance to showcase the vibrant colour palette of Ewan McDougall, whose paintings are like parties without the hangover, social anxiety, or contagious contact! The playfulness, the uninhibited looseness, the commentary on what's feral, undisciplined, undignified in both a glorious and sometimes a gross sense, all become very magnetic, absorbing, compelling as bonfires on a cold, dark beach.