Introduction

It is a tremendous honour to write an introduction to the 'life histories' of the Deans of the Otago Medical School – the men and women whose bold visions and passionate actions laid the foundation and growth of this iconic New Zealand institution.

The national impact it contributed to and the international standing and profile of this medical school are a testament to its audacity, inspiration, and courageous journey. Over nearly 150 years, the Otago Medical School has been evolving and this portfolio of Deans, put together by historian Dorothy Page, outlines this evolution masterfully.

As challenges and opportunities repeated over history, these men and women navigated the medical school through some turbulent financial and political environments and steadfastly pursued their visions. They placed the medical school's interest above all else and worked tirelessly to safeguard and build its reputation and profile. They painted the canvas, individually and collectively, to create, preserve and shape New Zealand's first medical school as we see it today and for generations to come.

Many of the Deans' life-size portraits were painted by Dr John Gillies, a graduate of the Otago medical school; each of these artworks is a masterpiece. These add character and voice to the life histories and are hung on the great walls of Colquhoun and Barnett lecture theaters of the medical school. Their gaze inspires and guides future generations of medical students and the history of the place.

Rathan M Subramaniam

MBBS, BMedSc, MClinEd, MPH, PhD, MBA, FRANZCR, FACNM, FSNMMI, FAUR

Portraits of the Otago Medical School Deans – an artist's perspective

Portrait painting can be an invidious undertaking. Art aficionados tend to shun portraiture because they feel that it compromises true artistic expression and the subjects themselves have preconceived expectations and not infrequently, an invested interest in the outcome. John Singer Sargent, the great society portraitist of last century, once said, “Whenever I paint a portrait, I lose a friend”. So clearly, it's a risky business! However, for me it is a special challenge for I believe that portraiture is where art and craft blend to form an enduring partnership. Within the confines of accurate reproduction (the craft) there is a need to produce something creative (the art) which catches the viewer's attention and hopefully, promotes the viewer's desire to find out the identity and other characteristics of the subject.

My first portrait for the University of Otago Medical School was of a former tutor of mine, Professor W E Adams, and was done post-mortem. I was given a black and white photo but was fortunate enough to have available his Leeds PhD gown, as well as the services of one of my relatives as sitter. The other seven were done ante-mortem, which gave me the opportunity to engage with the subjects. In fact, for me, that is the most important and enjoyable part – important, because I am able to position the subject in an interesting pose, making use of special lighting effects, and enjoyable, because I am able to have a conversation about medical matters of mutual interest and find out what is happening in my old stamping ground, the Otago University Medical School.

It is, of course, a privilege to be asked to paint portraits of former Deans, but it is a privilege that I treasure.

John Gillies

MB ChB (Otago), Dip. Av. Med., DOHP, FRACP

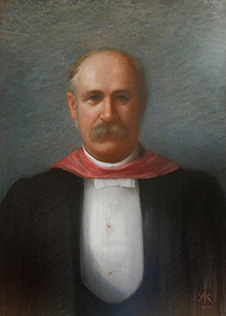

Professor John Halliday Scott (1851–1914)

J H Scott, painted by Frances Mary Wimperis (1910).

MB CM, MRCS, MD, FRS

Dean 1891–1914

John Scott, the first Dean of the Otago Medical School, came to the University of Otago as its founding Professor of Anatomy and Physiology in 1877. Born and educated in Edinburgh, he had completed an outstanding medical degree there and also had experience as a house surgeon and demonstrator.

The high regard in which he was held in the Edinburgh Medical School ensured that his proposed two year course was accepted as a preliminary to completion of study there. Four of Scott's first class of five, who began their course in 1878, went straight on to Edinburgh. He was fortunate in that he arrived in Dunedin just as the fine new University buildings were nearing completion, in time to make sound – and economical – recommendations on the accommodation required for a medical school.

As a teacher, Scott was clear and precise, illustrating his lectures with huge, delicately executed anatomical drawings, which are works of art in themselves – and a reminder that he was a talented water-colourist, who served as secretary to the Otago Art Society for more than thirty years.

As an administrator he was meticulous, but unwilling to delegate and never employed a secretary. A colleague noted that he did everything 'without parade or fuss.' His successor wrote simply that he 'was the Medical School'.

In 1881 Scott put to Council plans for a full four-year course and despite the financial constraints the University was enduring at the time the necessary staff were appointed, some of them local practitioners, others selected in Britain. Several would give outstanding service to the Medical School over many years.

The full course meant that students who could not afford the expense of completing in the UK could take their entire course in Dunedin. The first fully Otago-trained medical student graduated in 1887. It also meant that women, who were not eligible to complete at Edinburgh, could become doctors. The first graduated in 1896.

Scott's responsibilities as Dean, when a Faculty of Medicine was set up on his recommendation in 1891, did not alter his established combination of teaching and administration. Indeed, as time passed, some of his colleagues believed he was not open to new ideas.

Early in the new century the financial situation improved markedly, thanks to local fundraising and grants from the University of New Zealand. Student numbers rose sharply. When Scott died in 1914, having maintained his teaching schedule almost to the end, the student population of the Medical School was 155 and its presence was attracting other special schools to Otago, notably for Dentistry, Physiotherapy and Home Science. Scott's legacy was a securely established School.

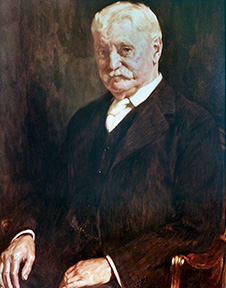

Sir Lindo Ferguson (1858–1948)

L Ferguson, painted by Archibald Nicoll (1937).

CMG, BA, FRCSI, MD

Dean 1914–1937

Henry Lindo Ferguson was born in England but grew up in Dublin. His father was a distinguished analytical chemist and founder fellow of the Chemical Society. An exceptional student, Lindo Ferguson studied industrial chemistry before deciding on medicine. He specialised in ophthalmology, and was made a Fellow of the Royal College of Surgeons, Ireland, in 1883. For health reasons he emigrated to New Zealand that year, settling in Dunedin because of its medical school and marrying within a year of his arrival.

The first trained eye specialist in Australasia, he soon developed an extensive practice, which also included ear, nose and throat surgery. He was appointed ophthalmologist to the Dunedin hospital and in 1886 also joined the Otago Medical School as part-time lecturer, later professor, on diseases of the eye.

A man of independent means and wide culture, a connoisseur of the arts, who would later bequeath his valuable collection of paintings to the Dunedin Art Gallery, he was also a generous host and a recognised leader of Dunedin society.

Ambition for the deanship does not seem to have been on his agenda. He was in his mid-fifties and contemplating retirement in England when Faculty elected him to the position on Scott's death in 1914. His vision for the Otago Medical School was infinitely broader than Scott's had been and he worked closely with a succession of Sub-Deans to implement it.

His master plan was to build and equip an entirely new Medical School opposite the Dunedin hospital, to increase staff numbers and improve conditions for them, to develop a research culture. He worked hard to secure the money needed for these developments, his early plans delayed but not halted by World War I. The first new building, partly funded through a successful public appeal and named for Professor Scott, opened in 1917. The next, after determined but always affable lobbying of successive governments, was the splendid four-storey building (1927) later named for him.

The close relationship of medical school and hospital was of great importance to him. He had already been involved in designing a new hospital building, the Campbell Pavilion, early in his career and at its end was influential in the provision of a new maternity hospital to facilitate obstetric training for students. Medical School staff were increased and the course was modernised and extended to a full six years. These changes did not come without often bitter opposition but Ferguson's campaigns were characterised by his quietly persistent approach and persuasive skill and he usually got his way.

He was honoured by a number of overseas medical schools, created CMG in 1918 and knighted in 1924. Sir Lindo retired from his work at Dunedin Hospital after fifty years' service in 1935 and as Dean of the Otago Medical School the following year. He died in 1948.

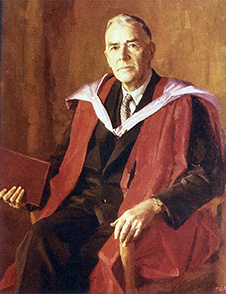

Sir Charles Hercus (1888–1971)

C Hercus, painted by Sir William Dargie (1958).

DSO, OBE, BDS, MB ChB, MD, LLD Hon

Dean 1937–1958

Charles Hercus was the third, and last, of the Deans to serve for more than two decades, ample time to put their special stamp on a School which they almost seemed to personify.

Brought up in Christchurch, Hercus came to Dunedin to study dentistry in 1908, one of the first cohort of students in the new Dental School, and also a foundation year resident of Knox College. On graduation, he enrolled in the medical course, which he completed in 1914, in time to enlist when war broke out. He was sent to Gallipoli – reputedly the only soldier to have carried a microscope ashore with him – in the first stage of a distinguished military career, recognised by a DSO in 1917 and an OBE two years later.

His wartime experience, especially with malaria control in Palestine, reinforced his commitment to preventive medicine, in research and teaching. After postgraduate study in Britain, he returned to Otago in 1921 as Professor of Bacteriology and Public Health. He had already identified a lack of iodine as the cause of the prevalence of goitre in New Zealand and the Department of Health had introduced iodised salt on his recommendation. His students were introduced to research methodology through a research-based thesis.

Hercus quickly became involved in the administration and politics of the Medical School. He served as Ferguson's sub-dean for thirteen years, an invaluable apprenticeship for taking over the deanship in 1937. Like Ferguson, he faced the pressures on the School created by the Government's wartime demand for more doctors, but he could also take advantage of the opportunities. The annual student intake was increased to 120, creating almost unmanageable numbers in cramped accommodation, but the School also benefited, after the war, by a third fine building opposite the hospital, later named for him.

In the prosperous post-war era Hercus achieved his aims of growth and research excellence, despite having to deal with powerful new players on the field: an Executive Vice Chancellor at the University and a new national funding body, the University Grants Committee. Staff numbers proliferated in Dunedin, and hospitals in the other three main centres were funded as branch faculties, to provide clinical experience for senior students. Research flourished, in conjunction with the Medical Research Council, newly empowered by generous funding and with a series of specialist subcommittees on which Otago staff predominated.

Hercus's influence was acknowledged across the wider Otago campus, as in the development of the Student Health Service, collaboration with the Dental School, and lobbying for a School of Physical Education. For the Medical School his tenure was a period of unprecedented expansion. He was knighted in 1947 and awarded an honorary LLD by his University in 1962.

In retirement, Hercus collaborated with Sir Gordon Bell on a history of the Medical School under the first three Deans.

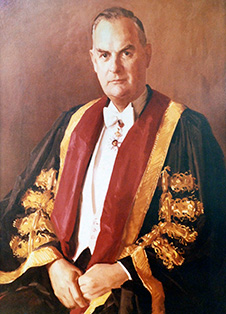

Sir Edward Sayers (1902–85)

E Sayers, painted by William Alexander Sutton (1967).

CMG, LEGION OF MERIT, MD, Hon DSc. FRCP, FRACP, HON FACP, FRSNZ, DTMSH

Dean 1959–67

Sir Edward Sayers was the first Dean of the Otago Medical School to serve a finite term of only a few years, rather than one measured in decades and ended only by retirement.

Born to a struggling family in Christchurch, he was sponsored by his church to study medicine. He then specialised in tropical medicine in London and spent seven years in charge of a Methodist mission hospital in the Solomon Islands. He was practising in Auckland when war broke out and enlisted promptly. His understanding of tropical diseases, especially malaria, was immensely valuable to both New Zealand and American troops in the Pacific region.

Back in Auckland after the war, he won an outstanding reputation as a physician and, as Sub-Dean of the Otago Medical School's Auckland Branch Faculty, as a clinical teacher. Among many honours, he became the first New Zealand President of the Australasian College of Physicians, chaired the Medical Council and was made CMG in 1956.

In 1959 Sayers returned to Dunedin as Professor of Therapeutics and Dean of the Otago Medical School. He began with attendance at a world conference on medical education and a tour of numerous Medical Schools in North America and Britain. In line with overseas trends, he immediately altered the senior curriculum at Otago to a focus on clinical experience rather than lectures.

In 1960 he negotiated in London a gift of £100,000 from the Wellcome Research Institute, to erect a new building dedicated to medical research and directed by Sir Horace Smirk. The momentum could not be maintained. Sayers' deanship coincided with major changes in the academic environment that were disastrous for the Medical School. The University of New Zealand was disestablished in favour of four autonomous institutions, funded through a newly empowered University Grants Committee, which could make academic as well as financial decisions. Otago's block grant was simply not enough to include the costs of running a modern medical school. At the local level, staffing was delegated to a University committee and there was ongoing acrimony over allocations.

At the end of 1967, when Sayers retired, the University Council chose to defer the appointment of his successor until a thorough external review of the School had been carried out.

Professor William E Adams (1908–1973)

W Adams, painted by John Gillies (1973). A posthumous portrait.

MSc(Hons), MB ChB, PhD

Dean 1968–1973

The deanship of Professor Bill Adams began in 1968 with the visit of Professor Ronald Christie of McGill University, invited to inspect the Medical School, to report on its problems and to suggest a way forward. Adams, who had been Head of the Anatomy Department since 1944, was initially appointed for the duration of the visit and then confirmed in the position, to oversee the implementation of the recommendations made.

The Christie visit marks a turning point in the history of the Medical School. Its problems, structural and financial, were well enough known, but Christie's international status and experience ensured that his blunt appraisal of them and his specific recommendations could not be ignored. He found staff salaries inadequate by international standards and the School generally underfunded 'to point of jeopardy.' Staff and students were working in old and often quite unsuitable buildings. Facilities at Dunedin Hospital were not up to requirements for clinical teaching and the Medical School was not represented on its Board. The curriculum needed updating and the urgent demand for more doctors could only be met by setting up a clinical school out of Dunedin to share training of the senior students.

Bill Adams, whose father was a Foxton GP, had begun his career with an Otago MSc Honours in Zoology before studying Medicine. After graduation in 1935 he worked for three years as a senior tutor in Anatomy, then took up a post at Leeds University, where he also completed a PhD. He specialised in neurology. With an admirable reputation for integrity, the readiness to work collaboratively, a raft of honours from learned societies in his field and a proven skill in administration, he was seen as the ideal person to implement the wide-ranging Christie recommendations. He was strongly supported in this by Clinical Dean Robin Irvine and University Vice-Chancellor, Robin Williams.

A great deal was achieved in a short time, in some cases – notably the foundation of not one but two clinical schools, in Christchurch and Wellington – going beyond the Christie recommendations. The student intake was increased, new staff were appointed, typically Otago graduates with British postgraduate qualifications, who would make their careers at Otago, new buildings were in process of planning.

Robin Irvine had been named as Dean Designate and enthusiasm was growing for the School's centenary in two years' time when Professor Adams died suddenly in 1973. Colleagues joined together to write an appreciative obituary for the New Zealand Medical Journal. As Dean, he had made a vital contribution to the resurgence of the Medical School in the 1970s.

Professor John Desmond Hunter (1925–2003)

J Hunter, painted by Grahame C Sydney (1978).

CBE, MB ChB, MD, FRACP, FRCP

Dean, first term 1974–77

Professor John Hunter has been the only person to serve two non-consecutive terms as Dean of the Otago Medical School.

Orphaned at an early age, he and his brother spent six harsh years in Auckland orphanages until a wealthy uncle intervened, sending both to King's college for their secondary education and the Otago Medical School for professional training. John Hunter graduated in 1948, winning the Travelling Scholarship, and was seconded to a cardiology course at Green Lane Hospital before taking up advanced study in the discipline in London.

He returned to the Otago School as a lecturer in 1956, and was made professor six years later. Always committed to the welfare and status of the Otago Medical School, he was proud of his role in publicising the problems that led to the Christie Report and the consequent changes.

He developed one of the country's first coronary care units, and fostered the development of cardiac surgery in the South. His services to cardiology included membership of the founding Council of the Heart Foundation in 1968, a term as its President a decade later and life membership in 1989.

A highlight of his first tenure was the celebration of the School's centenary in 1975, by which time much of the extensive building programme in all three centres was completed, the student intake had been increased to 200 and a new curriculum had been developed. As he wrote at the time, there had been 4,623 graduates from the Medical School, most of whom had remained in New Zealand – the 'backbone of one of the finest health systems in the world.' The celebrations extended throughout the year – as well as social events there was a special issue of the New Zealand Medical Journal, the award of honorary degrees to seven distinguished graduates, the establishment of a Medical Education Trust to promote postgraduate medical education and (strongly promoted by Professor Hunter) an Alumnus Association.

But the post-Christie boom was over by the later 1970s, money was tight and the National Government of the day did not give medical schools priority in its allocation. The University's block grant was inadequate and the Medical School's share of this was a matter of constant frustration and the cause of much bitterness. Hunter had little satisfaction in his position, trapped, as he felt himself to be, between the Otago University authorities and the Northern Clinical Schools. In 1978 he moved to Sydney as the inaugural Director of Continuing Education for the Royal Australasian College of Physicians. He must have felt better appreciated: the College awarded him its medal for his outstanding services.

In 1980 he returned to New Zealand as Dean of the Christchurch Clinical School, a role which gave him a unique understanding of the concerns of the Northern Schools when he resumed the deanship of the Otago Medical School in 1986.

Professor Geoffrey Brinkman (1921–2017)

G Brinkman, painted by W A Sutton (1985).

MB ChB, MD, MRCP, FRCP, MRACP, FRACP, FACP, DCH

Dean 1978–85

Born in Wellington and educated at Wanganui College, Geoffrey Brinkman entered Medical School in 1939, one of the intake that spent the war years theoretically under the control of the army, with all holidays given over to camp or barracks. He then moved to London for three years' postgraduate study.

On his return to Otago he was unexpectedly called on to take over as Acting Director of tuberculosis services and became absorbed in the field. He pursued it at an advanced level in the United States, during a twenty-year career in which his practical expertise was combined with publications on physiological, epidemiological and electro-microscopic research, and experience in high-level administration.

Back in New Zealand in 1976 Brinkman joined the Otago Medical School as Associate Dean for Postgraduate Affairs and Hunter's Deputy. When he took over as Dean in 1978 he was already acutely aware of the effect the recession of the late '70s was having on the School. The Department of Health's Advisory Committee on Medical Manpower recommended a 25 per cent cut in the student intake and argued that the School had 'at least one and a half clinical schools too many.' The Government reduced the 1981 second year class from 180 – already down from 200 – to 150.

Later that year the University invited David Bates, of the University of British Columbia, who had been in Dunedin during the Christie review in 1968, to assess the situation of the Medical School since then. Despite acknowledged difficulties, Bates documented 'remarkable progress,' strongly affirming the need for all three clinical schools. Nevertheless, the threat of closure remained. Money remained tight and Brinkman was intensely frustrated by his lack of autonomy and an absence of consultation on resources and staffing. There were substantial cuts in funding to all three campuses and the closure of one of them seemed inevitable. Suddenly, in August 1985, the new Labour Government announced an increase in the student intake to a viable 170.

Brinkman's vivid reports to the Alumni reflect the frustrations but also some positive developments of his term, notably a new Chair in General Practice. He retired in 1985 but from his seaside retreat at Waikanae must have appreciated the irony, as well as the honour, of his appointment as Chairman from 1986 to 1989 of the Advisory Committee on Medical Manpower.

Professor John Desmond Hunter (1925–2003)

J Hunter, painted by John Gillies (1990).

CBE, MB ChB, MD, FRACP, FRCP

Dean, second term 1986–1990

In several respects John Hunter's second term as Dean was less stressful then his first and certainly less fraught than that of his immediate predecessor. Some of the most apparently intractable problems simply disappeared, with changes in the leadership at all three Schools.

In Christchurch, Alan Clarke, who replaced Hunter, was used to working with him, in Wellington the abrasive Ralph Johnston was replaced by Tom O'Donnell and in Dunedin David Stewart assumed a new position recommended by Brinkman, a Dean of the Dunedin School, separated from the Otago Medical School Dean, to allay suspicions that the latter might favour the Dunedin campus. They were all Otago graduates, knew each other well and worked cooperatively. In a significant affirmation of status, the Clinical Schools were renamed the Christchurch and Wellington Schools of Medicine.

Finance remained a serious problem, but some changed procedures and a general rule of equal division of the bulk grant among the three centres removed much of the attendant bitterness. On the other hand, far-reaching changes in the Health and Education sectors, introduced by the former National Government and maintained after Labour took over in 1984, had a sharp impact on the Medical School.

In the Health sector, the new Area Health Boards struggled with their extensive responsibilities, and the strictly population-based funding of hospitals took no account of the needs of clinical teaching. In the University sector, Vice-Chancellors were limited to a renewable 5-year term. The University Grants Committee was disestablished and the search for private funding was encouraged.

At Otago the Faculties of Medicine and Dentistry were linked together in a Division of Health Sciences, headed by an Assistant Vice‑Chancellor: Hunter added this role to his other responsibilities in 1989. Additionally, there were more formal accreditation procedures under the Medical Council of New Zealand. When a delegation reviewed the Otago Medical School in 1988, it required from the Dean a huge amount of preliminary information, including his own assessment of the strengths and weaknesses of the School.

Whereas Hunter's first term as Dean had been focused on integrating the Faculty, his second, as he put it, was given over to ensuring financial equity and improving cooperation among the three Schools.

On retirement, Hunter moved to Wanaka, but ill health necessitated his return to Dunedin some time before his death in 2003.

Professor David Huston Stewart (1933–2015)

D Stewart, painted by John Gillies (1995).

NZ Medal 1990, MB ChB, MD, MRCP, FRCP, MRACP, FRACP

Dean 1991–1995

David Stewart was born in England and came to New Zealand as a child. He and his twin attended Waitaki Boys' High School, studied medicine at Otago, and graduated in 1956, David at the top of the class.

After time as a house surgeon, he spent four years on postgraduate study in Britain, specialising in thyroid physiology and disease, and then eight at the University of New South Wales Thyroid Unit.

In 1971 he was invited back to Otago as an Associate Professor, to set up a nuclear medicine department in the Dunedin hospital. He proved an outstanding clinical teacher and three years later was appointed to the Mary Glendining Chair of Medicine.

Stewart's involvement in high-level administration began in 1983. He worked closely with Brinkman, as his deputy and with Hunter as Dunedin Dean, when this position was separated from that of Otago Medical School Dean in 1986, and also served on the Otago Hospital Board. He was thus well prepared for his appointment as Otago Medical School Dean in 1991, in combination with a recently created position, Assistant-Vice-Chancellor Health Sciences.

The political environment of the 1990s was turbulent, with major changes in the areas of both education and health that crucially affected the Medical School. The University Grants Committee was disestablished and its five-yearly grants were replaced by annual allocations based on student numbers. At the beginning of Stewart's term a much-reduced grant necessitated a sudden halt to new staff appointments and replacements for those retiring, including some long-serving Professors.

Changes to the health system, where hospitals were expected to run as businesses and no consideration was given to teaching or research, seriously affected clinical teachers and a number resigned. Medical students suffered from higher fees and many accumulated debt under the new student loan scheme. The first inspection for accreditation by the Australian Medical Council, for which Stewart provided much of the documentation, occurred at this time and the resulting report, in 1994, was critical.

But Stewart also found significant opportunities in the new environment and viewed the period overall as one of expansion, with higher student numbers warranting additional staff and new or upgraded buildings on all three campuses, annual bulk funding providing greater flexibility in expenditure, and a more devolved administration facilitating the development of new courses and an enhanced research environment.

His role as AVC Health Sciences, which continued till 1998, complemented and reinforced his work as Dean, in cooperation with his successor in that role. New subjects, notably Physiotherapy and Pharmacy, were added to the Health Sciences portfolio, and from 1998 a new Health Sciences First Year course was required of all students planning health-related degrees, including medical students.

Stewart retired in 1999, but for some years worked as an endocrinologist at the hospital and used his strategic insights and negotiating skills on numerous local and national health-related bodies.

Professor (Archibald) John Campbell (1945–2016)

J Campbell, painted by John Gillies (2004).

MB ChB, MD, Dip Obst, FRACP

Dean 1995–2004

John Campbell grew up in Auckland and completed his MB ChB at Otago in 1969. After postgraduate study there, and later in Canada and the United Kingdom, he became a general physician and geriatrician.

From 1981 he held a joint appointment at the University of Otago and Wakari Hospital, where he made the Geriatric Unit a leader in New Zealand. He became Professor of Geriatric Medicine in 1984 and four years later Chair of the Department of Medicine.

An exceptional clinician, his patient-centred, practical teaching strongly influenced practice at Otago and in a number of Australian medical schools. Campbell published widely on the epidemiology of old age, presented at numerous international conferences and served as adviser to the World Health Organisation. His Otago Exercise Programme was adopted overseas as well as in New Zealand.

In 1995 he began a term of almost a decade as Dean of the Otago Medical School. It was a difficult time. Successive disruptive changes in the Health sector during the term of the previous Dean had impacted severely on clinical staff, caught between hospital and University in what was referred to as 'unbundling' the clinical (hospital) and educational (medical school) aspects of healthcare. The larger hospitals, now 'Crown Health Enterprises,' were funded strictly on a population basis, taking no account of clinical teaching or research.

In Dunedin popular dissatisfaction at this system, which involved funding cuts for Dunedin allocation and was exacerbated by the confrontational style of Healthcare Otago's Board, ran high and boiled over into public protest in 1997. The crisis lasted till mid 1998, ending with the resignation of the entire Board. Throughout, Campbell was a strong advocate of co‑operation between hospital and Medical School, an outcome he achieved in the latter years of his tenure. The documentation for the Australian Medical Council's three accreditation inspections in this period, and their reports, provide copious information on the problems and their eventual resolution. The 1994 report, at the end of Stewart's term, had resulted in the University restructuring the Medical School administration.

As incoming Dean, Campbell was given oversight of the Otago Medical School's three Schools of Medicine and also a new preclinical configuration, the Otago School of Health Sciences, which by 1998, in conjunction with the Dunedin School of Medicine and some University departments, had developed a common Health Science First Year course for all students planning health-related degrees at Otago. Campbell also oversaw extensive curriculum changes at the upper levels of the medical course. He co‑ordinated information from a wide range of specialist committees to present to the AMC team on their inspection visits of 1999 and 2004, in each case to a very favourable response.

He chaired the Medical Council of New Zealand from 2003 to 2009 and in retirement also took on a number of other roles, including expert geriatrician to the Courts of Cambodia in trials of senior Kmer Rouge leaders.

Dame Linda Jane Holloway (1940–)

L Holloway, painted by John Gillies (2006).

ONZM, DCNZ, MB ChB, MD, FRCPA

Dean 2005–06

Linda Holloway (née Brown) is the only woman to have served as Dean of the Otago Medical School.

Born in Scotland, she studied Medicine at the University of Aberdeen and began her long association with the Medical Women's International Association at that time. Among a number of awards she won as an undergraduate was a Travelling Scholarship in Pathology to the Karolinska Institute in Sweden, which determined her future specialisation.

She was a lecturer in Pathology at Aberdeen when she met John Holloway, an Otago graduate studying forestry. They married in 1970 and her early years in New Zealand, determined by her husband's occupation, were spent first in Gisborne and then rural South Otago. On moving to Dunedin in 1975 she was able to complete her specialist qualification and then, with her family, returned to Scotland, taking up a position as Senior Lecturer at the University of Edinburgh and completing her doctoral studies.

She returned to New Zealand in 1978 as a Senior Lecturer and in 1994 Professor at the Wellington School of Medicine. She remained for 19 years, the last two as Dean after the untimely death of Professor Eru Pomare. It was a difficult time, as the School was in financial difficulties and she had to complete a restructuring that had already been commenced. She placed a high priority on assisting affected staff to find alternative employment.

Holloway was already well known throughout the country as one of Judge Silvia Cartwright's medical advisers in the 1987–88 Inquiry into Allegations Concerning the Treatment of Cervical Cancer at National Women's Hospital. She would later continue her public service with a ten-year stint as Chair of the Abortion Supervisory Committee. Her contribution was recognised by the award of the New Zealand Honours of ONZM and DCNZ.

In 1999 she moved to Dunedin to the wider responsibilities of Assistant Vice-Chancellor, then Pro-Vice-Chancellor Health Sciences until 2005, when she was appointed Dean of the Otago Medical School until her retirement the following year. In her short tenure as Dean Dame Linda's priorities were enhancing collaboration among the three campuses and improving relations with the District Health Boards.

Since her retirement she has continued to serve the University, holding a number of interim appointments and teaching pathology to undergraduate medical students.

Professor Donal Muir Roberton (1948–)

D Roberton, painted by John Gillies (2011).

MB ChB, MD, FRACP, FRCPA, FRCPCH (Hon)

Dean 2006–2011

Don Roberton grew up on an isolated Taranaki farm; his first school had one teacher and 13 to 20 pupils. After secondary education at Kings College, Auckland, he studied Medicine at Otago, graduating MB ChB in 1971 and later MD. He completed specialist qualifications in Paediatrics and Pathology (Immunology) in Australia.

His career as a clinician, teacher, researcher and administrator began at the Royal Children's Hospital in Melbourne. When he was appointed to Otago, in the dual role of Pro-Vice-Chancellor and Otago Medical School Dean, he was described as one of the leading Health Science academics in Australia.

Roberton's term as Dean was notably productive in several areas. He regarded himself as fortunate in that Government funding for medical student education was substantially increased during his tenure. Considerably more student places were allocated, enabling the appointment of additional staff and development of important curriculum and educational initiatives. These included a new Health Science First Year programme, an Early Learning in Medicine (ELM) programme for second and third year medical students and an Advanced Learning in Medicine (ALM) programme for fourth and fifth years. Both of the latter encouraged self-directed learning with a strong practical component: case-based learning with an emphasis on clinical skills in the first, and a major extension of regional and rural placements in the second. A Rural Medical Immersion Programme was commenced. Clinical Skills laboratories were funded. Special consideration was introduced for the admission of more Māori and Pacific students, and extensive support was provided for them throughout their courses.

On all three campuses, Medical Education Units were set up and research in medical education and its outcomes was encouraged and supported. New research Chairs were established and new Associate Deans appointed. Among a number of new facilities, the Hunter Centre in Dunedin was established and a fine Wellington Campus building was commissioned. The Australian Medical Council awarded full accreditation to the School in 2008.

In other initiatives Roberton fostered collegial intercampus relations and staff communication through a regular Faculty newsletter, MediNews. He welcomed a new history of the Medical School, sponsored by the Alumnus Association, and contributed a perceptive, forward-looking end piece to it, in which he urged that the speed of advances in medical knowledge and in new technologies mean that the medical practitioners of today and tomorrow must commit not only to a future of lifelong learning, but also of learning how to learn.

Beyond the Otago Faculty, he initiated meetings with the Auckland Medical School Dean and Associate Deans, contributed to the work of Health Workforce New Zealand and initiated New Zealand's involvement with the Medical Students' Outcomes Database (MSOD), which assesses the long-term effectiveness of Australasian medical curricula.

Since his retirement and return to Australia Professor Roberton has served a term as Medical Director of MSOD and has been a member of high-level advisory boards in Paediatrics and Immunology, and especially vaccine programmes.

Professor Peter Crampton (1962–)

P Crampton, painted by John Gillies (2018).

CNZM, MB ChB, PhD

Dean 2011–2018

Peter Crampton was born in Somerset and came to New Zealand with his family when he was twelve. They settled in Nelson. He studied medicine at Otago, graduating in 1985, and then spent four intensely satisfying years practising in Porirua, where he helped establish a community health services centre. General practice remained of primary importance to him; it “grounded me and shaped my world view” he claimed, twenty years later. Nevertheless, he moved on, to work for communities on a broader scale, completing a PhD in Public Health and becoming Head of this department at the University of Otago, Wellington. He then served as Dean of the Wellington School for three years before moving South to take up the dual roles of Otago Medical School Dean and Pro-Vice-Chancellor Health Sciences at the University of Otago.

Crampton believed that medical practitioners in New Zealand should reflect the composition of the country's population and that people of Māori and Pacific ethnicity were seriously under-represented. Policy to implement this belief was summed up in the phrase 'a mirror on society.' With entry to second year Medicine strongly contested, this was controversial, but the University was supportive of the change and throughout Crampton's tenure as Dean the number of Māori graduates rose. In his valedictory report to the Medical Alumni in 2017 he could affirm that of the 282 domestic students accepted into second year, some 21 per cent were Māori and 7 per cent Pacific. Curriculum changes also responded to Māori and Pacific issues and new opportunities for leadership were created. Communication and team building were given high priority. The success of the policy was evidenced by a 10-year accreditation from the Australian Medical Council towards the end of his term. He himself was made a Companion of the New Zealand Order of Merit for his contribution to education and health sciences.

Since he left the Medical School and Health Sciences administration Professor Crampton has thrown himself into a crowded programme, involving academic work as Professor of Public Health in Kōhatu, Centre for Hauora Māori, policy work at a national level, as a member of the Health and Disability System Review Panel and the Board of the Wellington-based Health Quality and Safety Commission, and local commitments, as establishment Chair of the Board of Te Kāika, a South Dunedin Ngāi Tahu-led community health service combining medicine, pharmacy, physiotherapy and dentistry, and Deputy Chair of the Southern District Health Board.

Appointment of an Acting Dean

When Peter Crampton left the position of Dean late in 2018 he believed the Otago Medical School to be 'in good heart, with many research and teaching successes,' but he was deeply concerned that the University was implementing a major restructuring of its administrative support arrangements, which adversely affected many specialised Medical School support staff. Reallocation of administrative responsibilities at a high level was also under consideration because of the establishment of a new position at Otago, a non-medical Pro-Vice-Chancellor of Health Sciences, who would deal with matters hitherto part of the responsibility of the conjoined roles of PVC and Dean of the Otago Medical School. The University decided to appoint an Acting Otago Medical School Dean while recruiting for this position a person who would also be responsible for the Dunedin Medical Campus.

Professor Barry J Taylor (1952–)

Professor Barry J Taylor.

MB ChB, FRACP

Acting Dean October 2018–April 2020

Barry Taylor was born into a missionary family in the Democratic Republic of Congo and his early education was by correspondence lessons. When revolution broke out in 1965, the family was held hostage for six months; his father was fatally shot during a rescue attempt by UN troops and the rest of the family were brought back to New Zealand. These early experiences determined Taylor's later focus, as a paediatrician and teacher, to prevent wherever possible trauma or death of children.

An Otago graduate of 1975, Professor of Paediatrics and Child Health since 1998, and a former Head of the Department of Women's and Children's Health, he was appointed Acting Dean in late 2018. He added this role to that of Dean of the Dunedin School, which he had held for more than five years. As well as his experience in administration, Taylor brought to his new role a high research profile, both personally and as a team leader, with numerous widely cited publications over a range of topics, including Sudden Unexpected Death in Infants (SUDI) and child obesity. He was also co‑director of the Better Start National Science Challenge.

Among the issues he faced in his new position, as he described them to the Alumnus Association, was preparing a response to the Australian Medical Council, which had granted accreditation to the Medical School conditional on clarification of the revised role of the Otago Medical School Dean and the support available to the Dean under the shared services regime. He explained that the extensive building programme across the School's three campuses, while welcome, was causing sharp financial stress and requiring 'further efficiencies of function.' He also reported that the medical oath was being updated and at the next graduation would be heard in Māori as well as English and that two more categories of special admission to Medicine had been approved, for students from low socio-economic backgrounds and refugees.

Taylor's term extended beyond the end of 2019, but ended before COVID‑19 made its presence felt early in 2020. He has happily returned to teaching, supervising, research, and national project administration from a base in his home department.

Professor Rathan Subramaniam (1967–)

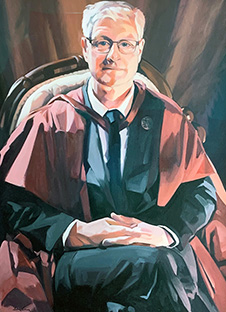

R Subramaniam, painted by John Gillies (2021).

MBBS, BMedSc, MClinEd, MPH, PhD, MBA, FRANZCR, FACNM, FSNMMI, FAUR

Dean 2020–2021

Rathan Subramaniam was born in a small Northern coastal town in Sri Lanka. He was the first in his family to attend a high school and a scholarship took him to Medical School in Melbourne. In 1999 he moved to New Zealand, completing his senior house officer year in Auckland, then training in diagnostic radiology at Waikato hospital – at the same time as completing a master's in Clinical Education from New South Wales and a PhD from Auckland.

In 2006 he took his young family to the USA, to enable him to specialise in nuclear medicine and neuroradiology at the Mayo Clinic. He then joined Boston University as staff consultant, while gaining a master's in Public Health from Harvard, followed by a stint at the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine and Hospital, where he was the Director of the PET/CT centre. He was then appointed Chief of the Division of Nuclear Medicine and Robert W. Parkey MD Distinguished Endowed Professor at the University of Texas Southwestern. His research was world renowned and awarded; by 2019 his publications included more than 240 articles and seven books.

His aim in coming to the Otago Medical School was to 'push the boundaries of medicine, science, education and health care delivery' to enable it to retain its place as one of the world's top medical institutions. His strategic priorities, which were built on the acknowledged strengths of the School, were to promote research excellence and transformative education, to progress a primary care and rural medical strategy to benefit all New Zealanders, to promote Māori and Pacific health and socio-economic equity and to advance national and international engagement.

A unique and unwelcome feature of Subramaniam's tenure was the disruption caused by the COVID‑19 pandemic. Classes had to be taught virtually, graduation ceremonies were cancelled. Throughout, he provided strong leadership and positive direction to the School.

Fostering research was always of prime importance, to train future physician scientist leaders for New Zealand. In Dunedin a Dean's research office and a Dean's research scholarship were established and the Dean himself conducted mentoring sessions for research students.

To the existing innovative intercalated courses MB ChB/BA and MB ChB/PhD – the second degree intertwined with the first, instead of taken after graduation – was added the Master of Public Health, MB ChB/MPH. Postgraduate courses in digital health, in partnership with the Otago School of Business, and genomic medicine were introduced. The number of students attracted to research or second degrees increased substantially.

Subramaniam relinquished the deanship at the end of 2021 and continues as a Professor of Radiology and Nuclear Medicine – teaching, leading many international oncologic clinical trials, as consultant at Dunedin Hospital and designing the Department of Nuclear Medicine for the new Dunedin Hospital.