Tuesday 16 February 2021 2:05pm

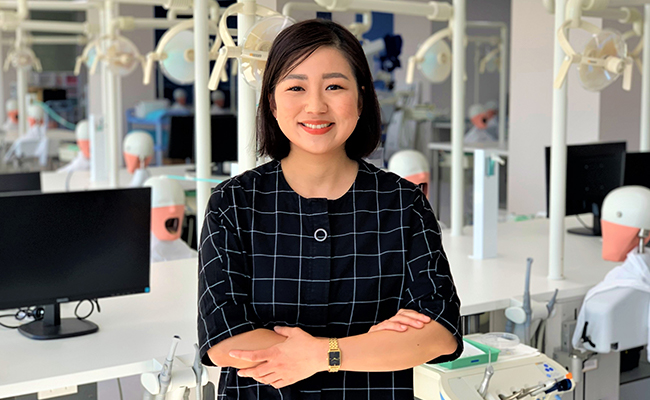

Dr Joanne Choi, in the University of Otago's Faculty of Dentistry.

Can a young girl from Korea really be plunged into New Zealand life, knowing nothing about the country, and succeed? Emphatically yes – and Dr Joanne Choi is the proof – but challenges abound.

Here and now, in 2021, Dr Choi is a model of success. She is a Senior Lecturer in the esteemed University of Otago Faculty of Dentistry – one of the world’s top dental schools. She teaches in the Dental Technology programme and is rapidly making a name for herself as a researcher of note.

But 19 years ago Dr Choi was simply Joanne, a 15-year old girl with limited English who had just waved goodbye to her mother. Alone in New Zealand to complete high school, Joanne had to adapt to a completely different life.

Dr Joanne Choi spent her childhood years in Korea's Chungju.

A Korean childhood

Growing up in Korea (in the regional city of Chungju) meant growing up knowing competition was king, Joanne says. From primary school onwards the education system was a battleground where children were driven to compete and succeed.

“Korea was a very competitive environment which my parents didn’t particularly like. They understood academics was very important but they say ‘that’s not how kids should spend their teenage years, or primary school’. You need the academics, but there should be another way to spend those years than just studying and going to after-school classes.”

Exams started at Year 1 and occured every semester. And those exams were important. While primary school places were allocated to children based on where they lived, from intermediate school onwards places had to be applied for. Entry to the ‘good’ intermediate schools was considered imperative for access to the good high schools, which in turn were vitally important to university options.

“So, from primary school, the way we were educated back then, you had to study hard and you had to do really well in the exams,” Joanne says. “It was very academic.”

That’s a stark contrast to New Zealand, where primary-aged children are encouraged to play, problem solve, investigate, find their passions and work collaboratively.

“Korea was a very competitive environment which my parents didn’t particularly like. They understood academics was very important but they say ‘that’s not how kids should spend their teenage years, or primary school’. You need the academics, but there should be another way to spend those years than just studying and going to after-school classes.”

When Joanne talks about ‘after-school’, she isn’t meaning the collective supervision service common in New Zealand. In Korea, after-school classes are a continuation of the school day.

For the young Joanne, primary school finished about 4pm.

“Then I’d have a little break, then there would be a shuttle that would take all the students to art classes, to art school, to practice for the competitions or whatever was coming up. And then I’d go to maths school or a cram school that would actually have all the subjects so students could learn all the different things. Then maybe I’d be back home by 8pm or 9pm. Generally Korean kids go to bed really late.”

When it came time to consider high schools, her parents decided to think outside the box.

New Zealand, new life

Joanne and her parents were determined her high school offer a great education in English; that meant Seoul, Korea’s capital city some 150 km away. But her family couldn’t afford to move to the capital with her father’s work based in Chungju. Instead, accommodation and living options would be needed for Joanne. Those would have been very expensive.

“So, my parents were weighing a few options.”

At the time, currency exchange rates meant sending Joanne overseas for her high school years was affordable. New Zealand was suggested, but it was not high on her radar.

“My English was quite good in the Korean system – when we’d get our English marks, I’d thought ‘oh, I’m really good’. But here, it was really hard to put a sentence together and talk to someone in the way I wanted to. That was a bit of a shock to me.”

“Actually, I knew nothing about it. I knew it was a country next to Australia, but not much other than that. I didn’t even know about kiwi birds.”

So, during her final year of intermediate school, with her mother and aunty Joanne did a round trip of New Zealand, to familiarise her with the country and culture.

“I liked the idea of going to New Zealand. I was very tired of all the exams and competitions. And it was more like ‘let’s go and have a look, you can always come back if it doesn’t work out’.”

She packed in case she chose to stay in New Zealand, but also left things behind in Korea – in case she returned.

“But when I came here, I really liked how I could actually spend time to read something or study something properly, and not just cram or have to memorise something for an exam, and everything being ranked. So that was one thing that really got me excited. And the fact I could make new friends and speak English. It was challenging but at the same time I was very much looking forward to it.”

She chose to stay, waved her mother off and at 15-years old was on her own, albeit staying with family friends – Korean Christian missionaries who ran a church in west Auckland’s Henderson.

She began at Te Atatu’s Rutherford College and immediately hit a snag.

“My English was quite good in the Korean system – when we’d get our English marks, I’d thought ‘oh, I’m really good’. But here, it was really hard to put a sentence together and talk to someone in the way I wanted to. That was a bit of a shock to me.”

Another shock was New Zealand’s cultural diversity.

New cultures, new habits

Schools in Korea were ‘very Korean’, Joanne says. In her New Zealand school not only were there very few Koreans, there was also considerable diversity – something she’d not encountered before.

“It’s one thing I really liked. There were Japanese, Chinese, other Asian friends that all came from different countries. I got really excited to make friends from all different countries, and also Kiwi friends.

Joanne attended west Auckland's Rutherford College.

“But at the same time, I realised everyone has different cultures and different ways to make friends. It wasn’t as easy as I’d thought. That was a bit of a shock because I used to be quite social, I had lots of friends back in Korea. Here, it took me a few weeks to actually get to know everybody.

“Taking art was quite good because I realised that, compared to other subjects, I didn’t need to talk too much. I could just do some good drawings and everyone would be like ‘oh, how did you do that?’.”

She also had support from the school’s international students’ group, ESOL classes, and staff who actively helped her and other international students make Kiwi friends.

Bullying wasn’t an issue, she says “except some boys, being that it was high school”.

Perhaps the biggest change was time – she suddenly had lots of it. In New Zealand, extra classes after school isn’t a part of the system. What did she do instead?

“My homestay got me to play some sports, which was really good because I was never good at sports.”

In Korea, sport was a subject that was tested and marked. In New Zealand she soon discovered sport was part of the country’s social fabric. Joining in helped with friends, but there was still a lot of time left over.

“And the big thing about having so much time after school, not going to those cram schools, is that it really helped me find independence in my own learning. At the beginning I found it very strange, you know, ‘I have so much time, I’m done with my homework, what do I do? How do I spend my time?’

“I felt like in the past I’d never really had my own way of learning or my own schedule. I was always given a schedule to study something so I could do well. Whereas here, you need to motivate yourself. For the first time I really learned to be responsible for my own learning. I got to develop my independence.”

Gaining independence so early has, she says, been an important part of her subsequent academic success.

Joanne and her family at her PhD graduation.

The university challenge

As high school ended, university beckoned. Joanne was weighing up art school options but had also done well in science and maths.

“I didn’t really want to do something like chemistry, or a pure science degree. And I learned that in order to get into dentistry or medicine I had to do Health Science First Year which adds another year to your university studies. Paying international student university fees was going to put financial pressure on the family. So, I was looking into other options I could finish in three years, but still a professional degree so I could use it.

“I remember a lot of my friends would go to costume parties, dressing up in togas and things like that. Guys dressing in togas – that was a bit of shock! That was something I hadn’t experienced before. But it was really fun.”

“With all that background my course adviser told me about Dental Technology, but said ‘it’s only available at the University of Otago, in Dunedin’.”

Before long she had moved south and was living in City College (now Caroline Freeman) with hundreds of other teenagers in a city famed for its reputation as a ‘free’ environment for first-year students.

“That was very different for me! I had a friend from Balclutha who had never had an Asian friend. Then there was a guy on the same floor, an art student, and he stacked all the beer cans in the common room. Apparently he was making some sort of art, but it was very smelly.”

Dental Technology’s small size – her class had about 30 people in it – meant making friends there was easy, and she moved into a flat with some of those friends for her second year.

“Then I really got to enjoy Dunedin culture.”

Studying together, flatting together, flat parties and more – it was a far cry from the strictures of Korea she’d been used to just a few years before.

“I remember a lot of my friends would go to costume parties, dressing up in togas and things like that. Guys dressing in togas – that was a bit of shock! That was something I hadn’t experienced before. But it was really fun.”

Work and earthquakes

She finished her three-year degree and was invited to do a full-year, research-based honours programme. She had done well in a research component of her degree, where the students had to solve problems, find answers.

“I really enjoyed doing the third-year research paper, and I did really well. There was a Dental Council prize for the best research student, and I got that. So, I thought it sounded like a really good option. But I had to convince my parents to actually let me study for another year.”

While the exchange rate had been favourable when she’d first come to New Zealand in 2002, that was no longer the case. In fact, in her third year at Otago her parents moved her younger sister, who had also been at Rutherford College, to Dunedin to save money.

“After we came back from that six-week break everything else was gone around us. There had been some tall buildings, and now we were sitting in the lab saying, wow, we never used to have this view. It was just an empty city."

“We actually stayed together in one room. They are all good memories now, but back then my sister was in her final year of high school, I was in uni and, you know, different lifestyles, different stages in life.

“So, I had to convince my parents to let me study one more year with international student fees, and convince them I really wanted to do this. I said, ‘if you give me one more year I’ll do really well’. And I really enjoyed it. I did do really well.”

The next year, 2010, she moved north to Christchurch, and her first Dental Technician job. With dental technicians being on New Zealand’s skilled migrant list, permanent residency soon followed. She loved the job, but later that year Christchurch started shaking.

“I was actually in the lab, in the city, when the big one (February 2011 Christchurch earthquake) happened. I remember all the small buildings, some of them were on fire, lots of smoke coming out. And because we had lots of Bunsen burners, lots of sharp instruments, hand pieces and things like that, as soon as it happened I remember my boss yelling to turn off all the gas and get under the bench. I remember it was all shaking, everything dropping. It was very chaotic. And because it was in the city area it was in the red zone, so we didn’t work for five or six weeks after that.”

The city was left in ruins and 185 people were killed. Joanne was unhurt but her building was damaged.

“After we came back from that six-week break everything else was gone around us. There had been some tall buildings, and now we were sitting in the lab saying, wow, we never used to have this view. It was just an empty city. “

She ended up spending four years in Christchurch, and realised working in the industry gave insights into problems technicians have.

“I think it was very good to have that four years. It helped me develop problem-solving skills and to think about the things I studied, the things I’d read and researched. And I was able to say, ‘oh, this is how people use it’. I came to realise why people do research. Because at the end of the day it will be applied by the people who actually use the materials and use the machines.”

An academic star emerges

“I was happily settled in Christchurch, but I was feeling a little bit automated. I think deep inside I was looking for a challenge.”

One day she got a call from a previous University of Otago supervisor, detailing a PhD scholarship and an interesting topic. She accepted, returned in 2014, worked hard, was published, and hasn’t left.

Dr Joanne Choi

Amidst her PhD work a first-year lecturer role became available. She was asked to apply – further cementing her ties to the university. As well as lecturing she has been published numerous times, won several awards, and has made the New Zealand news for her ongoing development of novel materials for children’s tooth crowns.

She also finished her Clinical Dental Technology postgraduate degree while working as a lecturer, allowing her to see patients directly, at the university and in private practice, for complete dentures and partial denture treatment.

Choosing to study Dental Technology, she says, was a lucky masterstroke. It allows people numerous options – both in the private sector and as an academic.

“You can choose to become a dental technician and choose to work in a lab, or there’s clinical dental technology where you can see patients and work directly with the public, but also do lab work.

“And because there’s a strong research focus, students can become staff, like me, or work in research and development in big dental companies; they normally prefer dental technology students because they want to develop something the technicians will actually use.”

Some of what Joanne is currently working on has commercial potential, and the university is helping take those innovations to market.

“It really is a subject that gives you back what you put it.”

Being an international student in New Zealand

Joanne is certain her move to New Zealand, despite the initial language and culture challenges, has helped with her success.

“I feel that at every stage where I had to make big decisions, I was always treated fairly. No one said ‘you can’t do this because you’re a female’, no one said ‘you can’t do this because you’re an international student’. I felt like my work was valued more than my background, which is very fair. In Korea, sometimes your age, your gender, there can be other things that impact where you go. There are a lot of glass ceilings.

“But in New Zealand I feel like through my high school, the University of Otago, my jobs at Otago and even working in Christchurch, it felt like everyone really gave lots of options to me. They said, ‘if you work hard for it, you can get it, it doesn’t matter whether you’re Korean, female, young’, things like that. That made me feel very lucky that I’m living in New Zealand, that I get to live here.”

She enthusiastically encourages other international students to give New Zealand a chance.

“Oh yes, I feel like in New Zealand everything is open, and the people are open minded. You can earn what you work hard for. You won’t be discouraged or limited here.”

But there are challenges, she says.

Joanne and her sister Jane - both now Otago Faculty of Dentistry staff.

“Sometimes my friends or relatives back in Korea, even my parents, say ‘have you ever thought about coming back to Korea?’. Which sounds really good, and sometimes I feel a bit sad that I can’t go back too often because of the distance, and now with COVID and everything, I can’t see my parents and I can’t be there as soon as possible if they’re sick. There are things like that I always think about and feel a little bit sad about.

“But I think now the world is very international. It doesn’t matter if you’re here or in Korea. I feel like one shouldn’t feel locked into their own country.”

She enjoys her lifestyle in Dunedin, too. She goes to the gym, walks around the city a lot, spends time with her sister (who is also now University of Otago staff) and friends.

“I actually have some friends from Rutherford College who moved to Dunedin for their job, so we have small gatherings together. That is really good, to have old friends.”

The future is wide open for her, though exactly what that future looks like, she’s not sure.

“I’d wish for all my current research projects to have really good outcomes. Things like the development of crowns for kids, I really hope they work out really well and they make a big difference in how we do dentistry and dental technology. So, that’s one thing.

“Another thing I’m currently focusing on is trying to help a lot of students get into different areas in the dental technology field and have successful careers. For my research students, I’m trying to give as much support as possible for their projects so they can get a PhD and become academics in the future. So, I wish in the next 10, 20, 30 years that I can really encourage other students to take on my path.

“At the moment I just see myself staying here and enjoying doing what I do. And hoping I really do well and become a professor one day!”