Thursday 9 June 2022 1:32pm

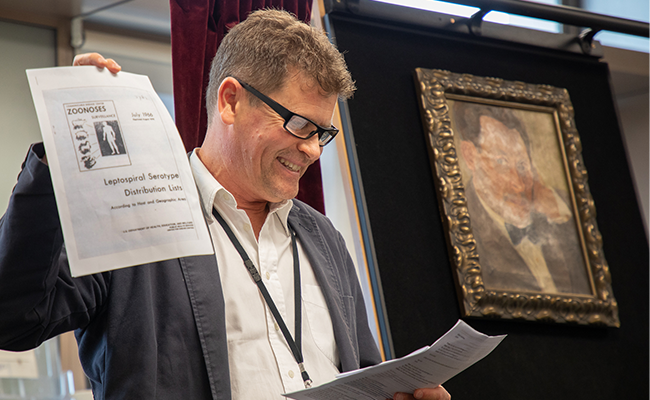

The portrait of Dr Leopold Kirschner, donated by his family

A portrait of the late, internationally recognised leptospirosis researcher and survivor of both World Wars, Dr Leopold Kirschner, has been unveiled at the University of Otago’s Department of Microbiology and Immunology.

The portrait honours the world-famous researcher’s service to scientific discovery and acknowledges the personal plights he overcame in order to do this, including serving in World War I (WWI) and surviving as a captive in World War II (WWII).

The piece was gifted to the University of Otago by Dr Kirschner’s family, some of whom flew in from Australia for the commemorative event.

Dr Terry Maguire, retired academic staff, Department of Microbiology and Immunology; Dr Elizabeth Whitcombe, Honorary Research Fellow, Centre for International Health; and Professor John Crump, Centre for International Health, in front of the portrait of Dr Leopold Kirschner, the culmination of 5 years work with Dr Michael Maze, University of Otago Christchurch (not shown) and descendants of Dr Kirschner

The unveiling was organised by Professor John Crump, Co-Director of the Centre for International Health and a member of the Otago Global Health Institute Leadership Team, as he felt Dr Kirschner’s contributions deserved to be appropriately acknowledged.

“We are thrilled that the family of the late Dr Kirschner was not only willing to donate the portrait, but also to attend this special event,” Professor Crump says.

“Dr Kirscher is a well-known researcher, especially in the field of leptospirosis, and so we wanted him to be recognised at the University of Otago as being a central figure in the discovery and early descriptions of leptospirosis in New Zealand, an important occupational disease of farmers and meat workers.”

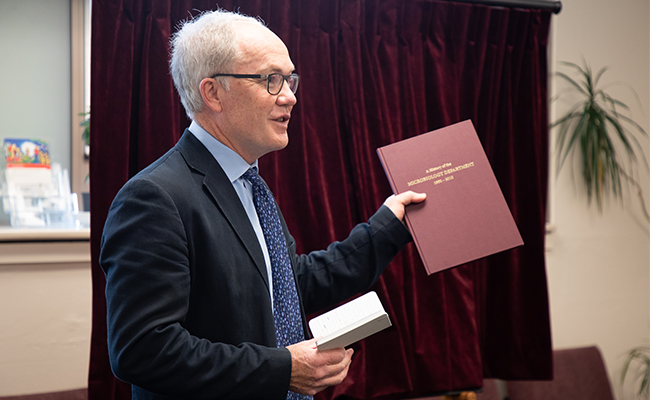

Professor Greg Cook, Head, Department of Microbiology and Immunology, describes the history of his department.

Born to Jewish parents in Poland in 1889, Dr Kirschner studied medicine in Vienna, only to have his studies interrupted by being called to serve in the Medical Corps during WWI.

At the conclusion of WWI in 1918, Vienna became a place of great political unrest and anti-semitism.

It was very unsafe for Dr Kirschner to remain there after completing his WWI service and medical studies so he decided to follow his Professor at the time, experimental pathologist Robert Doerr, to Amsterdam’s Dutch Tropical Institute, where the first leptospirosis reference laboratory in Europe had been established.

He left the Institute in 1921, to serve as the Deputy Director of the Pasteur Institute in Java, Indonesia (then the Dutch East Indies), where he would prepare vaccines and diagnostic services for 70 million people.

It was during this time that he did valuable work on leptospirosis research and additionally, alongside a coworker, developed a working vaccine against plague; the early versions of which they even tested on themselves.

Professor John Crump, Centre for International Health, recounts the story of how, while reviewing a 1966 US report of leptospirosis worldwide, that he and then PhD student Dr Michael Maze realised that internationally renowned leptospirosis researcher Dr Kirschner spent the latter part of his career at Otago

In 1942, his work was cut short by the effects of WWII, when the Japanese invaded Java and both Dr Kirschner and his wife Alice, a gifted Viennese violinist, become prisoners of war.

During this time, he would put his medical skills to use, caring for other captives and bartering for extra food for them as they worked in appalling conditions under the Japanese forces.

Dr Kirschner was even able to conceal a radio in the corner of his laboratory, which he labelled as “highly infectious material”, so he could listen to updates from the BBC.

At the conclusion of WWII, Dr Kirschner and his wife were freed and recruited by the University of Otago Medical School Dean, the Sir Charles Hercus.

Sir Charles employed him into the University’s “Medical Research Council Microbiology Unit” where Dr Kirschner, who was 57 at the time, would not cease in his research endeavours.

He became the first to discover the presence of leptospirosis in New Zealand and develop procedures for the identification and characterisation of the bacteria.

At the time, the country was considered to be free of the disease and so Dr Kirschner’s confirmation of human leptospirosis in 1949, and the first livestock-associated outbreak among dairy farm workers in 1951, was an important discovery for public health in New Zealand.

Professor Richard Blaikie, Deputy Vice-Chancellor, Research and Enterprise, who represented the Vice Chancellor and unveiled the portrait

Dr Kirschner died on 23 November 1970 at the age of 81 and is buried in Dunedin’s Southern Cemetary alongside his wife Alice; after whom the “Alice Kirschner Prize in Music”, that is offered at the University’s School of Performing Arts, is named.

His remarkable story has transcended his lifetime. The next generation of leprospirosis researchers in New Zealand that he inspired would later name a major pathogenic Leptospira species, Leptospira kirschneri, in his honour in 1992.

“The life of Dr Leopold Kirschner is one deserving of far more recognition than it has had, as his tenacity to continue the pursuit of research through so many trials is truly inspiring,” Professor Greg Cook, the Head of the Department of Microbiology and Immunology says.

“A considerable thank-you is extended to the family for providing us with the portrait so we can appropriately honour him and for coming here all the way from Australia to celebrate his life alongside us.”