Gender justice

In an interview with Brigid Inder, the subject of her 2014 OBE for services to women's rights and international justice is never discussed. There is simply too much else to talk about – namely the work for which she received the honour – although the fact that such work is necessary says much about the persistence of gender-based injustice in today's world.

For 10 years Otago alumna Brigid Inder has been executive director of the Women's Initiatives for Gender Justice, an international human rights organisation formed in 2004 to monitor and advocate for gender-inclusive justice through the International Criminal Court (ICC). The ICC is the permanent international

court set up in 2002 to try cases of crimes against humanity, genocide and war crimes in instances where national courts are unwilling, or unable, to investigate or prosecute such crimes.

In 2012, Inder was invited by the ICC's newly-appointed prosecutor Fatou Bensouda to take on the additional pro bono role of special advisor on gender. In this capacity she provides strategic advice to the ICC's Office of the Prosecutor on gender issues, including gender considerations within the analysis,

investigation and prosecution of sexual and gender-based violence, and her initial task has been the development of a policy on sexual and gender-based crimes – a first for an international tribunal or court.

Inder's long career in advocacy, policy negotiations and hands-on experience with women and disadvantaged communities has prepared her well for her work and this role.

“It brings together gender equality and justice issues,” says Inder, “and enables me to influence the policies of an international institution and, ultimately, to help shape its investigations and prosecutions, to ensure the inclusion of sexual and gender-based crimes.”

From Dunedin, Inder graduated from the University of Otago with a Bachelor of Physical Education in 1987. She began working with the YWCA in the late 1980s and travelled on a scholarship to Bangladesh, where she was exposed to the impact of poverty and natural disaster on communities, particularly on

women and children. She worked in Australia on HIV-related initiatives managing community health, HIV treatment and prevention programmes and was later appointed director of New South Wales' community legal centres, providing communities with access to legal advice and representation, as well as human

rights education.

During this time Inder became deeply interested in women's human rights globally and the role of the UN as an international policy-making body. She began attending sessions of the United Nations Commission on Human Rights (now the UN Human Rights Council) and was involved in several UN conferences advocating

and advising governments on gender issues in relation to sexual and reproductive rights, women in armed conflict, HIV/AIDS and the rights of children.

In 2002 she was appointed executive director of the Women's Initiatives for Gender Justice (Women's Initiatives), cementing a relationship with the ICC that was to become twofold in 2012 on her appointment to the special advisor role.

The terrain of the Women's Initiatives is not for the faint-hearted: systematic rape, sexual slavery, sexual violence, torture, mutilations, and the conscription of child soldiers and use of children in armed conflict. Much of their work aims to build the capacity of, and partner with, women's rights

and peace organisations in armed conflicts, advocating for domestic accountability for gender-based violence, more services for victims/survivors of these crimes, better laws prohibiting sexual violence and an end to armed conflict and pursuit of peaceful resolutions. They also work with the ICC to advocate

for the inclusion of sexual violence within the investigations and prosecutions, usually arising in areas where the rule of law has broken down.

History, however, indicates that justice for gender-based war crimes is notoriously difficult to achieve. Inder points out that rape and other forms of sexual violence were historically conceptualised as being about protecting a woman's honour – what it meant to be an honourable woman and what it meant for men to have an honourable wife. Rape was seen as indecent rather than as violent. “In that sense we have come a long way, moving from the idea about a special respect for women to recognising women's human rights, and ensuring the ability and rights of victims/survivors of sexual violence crimes to bear witness to these acts.”

It was only in the late 1990s – in the International Criminal Tribunals for Rwanda and the former Yugoslavia – that sexual violence was prosecuted as a crime against humanity.

Although important jurisprudence exists, the tribunals and the ICC have a mixed record in relation to crimes of sexual and gender-based violence. As a result of constant external advocacy – in large part by the Women's Initiatives – the ICC has included sexual violence charges in more than 70 per cent of its cases. However, as Inder explains, while the court has an excellent charging record for these crimes, it has struggled, as have the Yugoslav and Rwanda tribunals, with proving the specific liability of the perpetrator who, as a commander or political leader, is often not present during the incidents of rape committed by soldiers or combatants under his command.

“In the recent Katanga judgment at the ICC, where Germain Katanga [leader of the Front for Patriotic Resistance in Ituri] was convicted of all of the crimes for which he was charged in relation to an attack on a village in eastern DRC, except for the sexual violence crimes and the crimes relating to the enlistment and conscription of child soldiers,” says Inder.

“This is an example of a subconscious, but clear, bias by the judges expecting something additional – something unique – to prove Katanga's specific responsibility in relation to rape and sexual slavery committed by the militia group he commanded, which the judges did not require for the other crimes for which he was convicted.

“The chamber was satisfied that Katanga contributed to murder, destruction of property and pillaging – all of which occurred during the attack. They believed the sexual violence witnesses, and stated that they believed the rape and sexual slavery had occurred, but they were not satisfied that Katanga's contribution to the attack – which enabled the commission of the crimes for which he was convicted – also enabled the commission of acts of rape and sexual slavery. “This case is emblematic of so many of the ways in which sexual violence is treated differently and where a higher standard is subconsciously required to satisfy the threshold of beyond reasonable doubt."

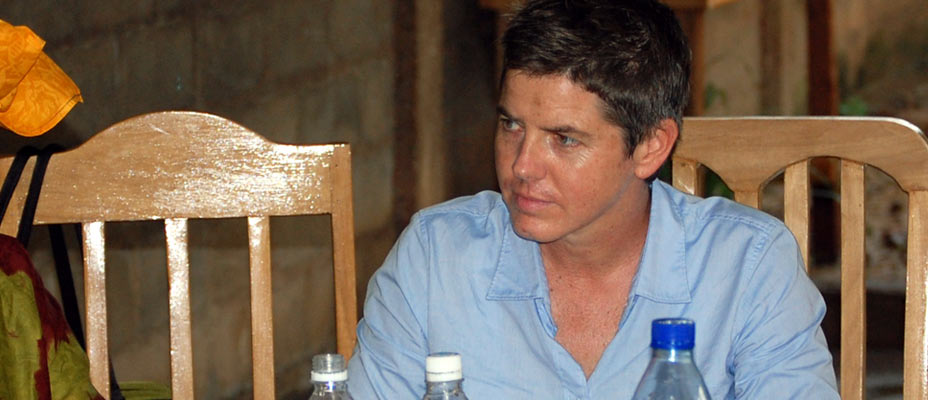

Brigid Inder: "… we have come a long way, moving from the idea about a special respect for women to recognising women's human rights, and ensuring the ability and rights of victims/survivors of sexual violence crimes to bear witness to these acts.”

"Unlike other international tribunals, the ICC faces the additional challenge of conducting investigations while conflict is continuing. Inder says this makes it enormously difficult for the court to access crime scenes and, because of widespread displacement, it also creates difficulties in locating potential witnesses.

“It makes witness security issues even more complicated, reducing the availability of documentary and forensic evidence, and the ability to follow up with individual witnesses who may be able to testify in support of charges. The impact of operating in areas of armed conflict can't be underestimated.”

Inder also points out that, in its early days, the ICC's investigative strategy tended to rely too heavily on open-source material – NGO or UN reports – documenting sexual violence rather than witness testimonies and other direct, primary evidence to support the sexual violence charges. As a result, she says, more than half of the charges were dismissed before trial.

In the past few years the ICC's record has improved in this area. “Two years ago around 50 per cent of the charges for sexual violence were being successfully confirmed for trial. Now around 61 per cent of these charges are being confirmed,”

It's in this area that Inder and the Women's Initiatives are very familiar. Together with in-country partners in the DRC (Democratic Republic of the Congo), the Women's Initiatives conducts a documentation programme interviewing victims/survivors of sexual and gender-based crimes and uses this data with domestic decision-makers and prosecutors, as well as with the ICC, to advocate for thorough investigations into these incidents.

“We have had a documentation programme since 2006 and, since that time, we have documented over 1,000 incidents of rape, sexual slavery, mutilations in the context of massacres, attacks on villages, large-scale military operations and individual attacks on women and girls in the margins of an armed conflict.”

The Women's Initiatives also advocates for gender justice in domestic processes at the national level and Inder is looking forward in 2015 to working with female former child soldiers in Uganda, assisting local partners in the development of an alternative rape law for Sudan, working with Libyan women's rights advocates for the establishment of services for victims/survivors of sexual violence, and to launching a new programme in the DRC aimed at strengthening local judicial processes in relation to sexual and gender-related crime.

“The ICC will always be limited in the number of prosecutions it can pursue,” she says, “so we're moving towards pursuing domestic prosecutions with a pilot project focusing on one province in eastern DRC. Even though the conflict is ongoing, local courts and military tribunals exist and are operational to some extent. Together with two other organisations, we are going to launch a programme that will train local lawyers and prosecutors in how to prosecute cases of sexual and gender-based crimes. This will also provide training for local judges so they are more informed about analysing the evidence, hearing testimony of sexual violence victims and witnesses, and are also aware of the international jurisprudence on these issues.

“We simply can't wait until the conflict is over to move forward with accountability for the crimes. Communities affected by armed conflict are calling for an end to the violence and demanding accountability.”

Despite the territory being familiar, Inder admits the nature of her work can be disturbing.

“Reading interviews with women and girls describing their abduction by the LRA [Lord's Resistance Army in Uganda or South Sudan] or their abduction and recruitment by other militia groups, or rape and sexual enslavement committed by armed forces or any number of militia groups in eastern DRC … that can be very disturbing, and in ways that you don't initially notice. It's only later that you realise you've become sensitive to sounds or sudden movements, or that you're agitated by unexpected loud noises in ways that you didn't used to be. Of course, this passes, but it creeps up on you in ways you don't necessarily notice at the time. We try to be conscious of this, working on other programmes, talking with colleagues and, for me, music and exercise are all ways to deal with these issues so you don't become overwhelmed by the tragedy and brutality.”

A good day at the office can be one of many things. “An indictment which includes sexual violence charges, progress in one of the local collaborative programmes, the inclusion of women in transitional justice processes, or women we work with standing for election.” Inder refers to growing support within Sudan for reform of the domestic rape law to comply with international standards, for example, or provincial leaders in eastern DRC passing an ordinance prohibiting mob violence and attacks against women accused of practicing “witchcraft”.

“It's not all battling up hill without progress. Our local partners and the Women's Initiatives are seeing signs of progress within countries and at the ICC which makes this period an important juncture in many of our gender justice programmes.”

REBECCA TANSLEY