Pandemic disasters: what have we learnt?

2018 is exactly 100 years since the end of World War 1, which killed around 18,000 New Zealand soldiers. It also marks the centenary year of the flu pandemic of 1918-19 which was this country's worst public health disaster. New estimates of around 9,000 flu deaths in two months far surpass our next biggest natural disaster, the 1931 Hawkes Bay earthquake in which at least 256 died.

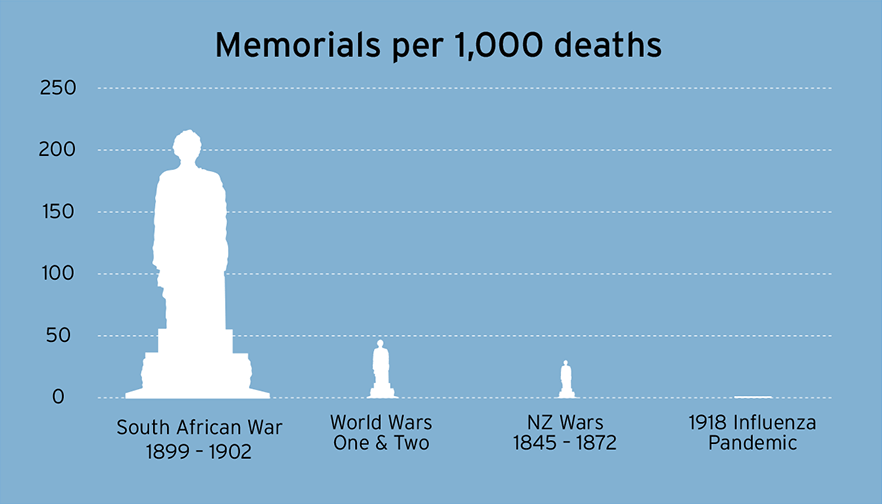

Despite killing almost one per cent of the population, the severity of the flu pandemic seems to be largely forgotten. We have very few memorials, and no national commemorations for the volunteers, nurses and doctors who were part of the pandemic response.

So in February, as part of its annual Public Health Summer School, the University of Otago, Wellington held a centenary symposium to review the 1918 pandemic and what we've learnt for modern day pandemic planning.

"Most societies are ill-prepared for pandemics, earthquakes, extreme weather events and other disasters. It is therefore important to study these threats so we can learn how to prevent them or mitigate their effects and respond more effectively," suggests Professor Michael Baker, an expert on infectious diseases and co-organiser of the Public Health Summer School.

“Public health researchers have a role in maintaining our collective memory for hazards that may return long after they have disappeared from daily life, and reminding us of questions that need to be asked and responded to. We also teach disciplines such as epidemiology at the Public Health Summer School each year, which provides a way of thinking about threats to health and how we manage them.”

The symposium reviewed the historical epidemiology of the 1918 pandemic in New Zealand, the international picture, contrasting patterns from New Zealand, Australia and South Pacific Islands, and an extra focus on the impacts on different ethnic groups. Speakers also looked at comparisons with more recent influenza pandemics (1957, 1968, 2009), and asked why the 1918 pandemic was so severe and what range of severity can be expected in future.

“The symposium had a good mix of history and lessons for the future – including useful updates on what New Zealand is doing now for pandemic planning,” says Professor Nick Wilson.

In reviewing the 1918 pandemic, Wilson says there was a disproportionately high death rate for Māori in successive flu pandemics (1918, 1957 and 2009), but particularly 1918 with a seven-fold higher death rate compared with the European population. This difference could reflect many factors such as exposure to a milder “immunising wave” of infection in spring 1918 (which may have helped protect people in cities), the role of pre-existing conditions such as tuberculosis, and access to supportive nursing care in rural areas where most Māori lived.

Another notable feature of the pandemic was the much higher death rate for adults in their late 20s. One possible explanation is that this age group was exposed in infancy to an earlier pandemic (in the 1890s) which impaired their immune system response to the 1918 pandemic.

Wilson says the pandemic's impact on crowded military training camps and troopships was particularly severe.

However “living rurally was somewhat protective against dying in the pandemic for the civilian population, probably reflecting a lower risk of becoming infected in the first place”. Also, good organisation of nursing care and basic support in cities such as Christchurch may have lowered the death rate compared, for example, with Wellington. But, in general, there were few successful control measures used in New Zealand at the time.

“Lessons from the 1918 flu pandemic can help us make better decisions when coping with the next one,” suggests Professor Geoff Rice, who gave the keynote public lecture on the pandemic at the opening of the Public Health Summer School. He has also recently published a book on the pandemic, Black Flu 1918, which has the updated best estimate of 9,000 deaths.

Rice highlights the need for community resilience: this helped in 1918, particularly with the provision of basic care by volunteers. He says the value of community response was shown more recently with volunteer effort around the Christchurch earthquake.

On this topic, Baker suggests a possible national Public Health Day as a potential awareness raiser and aid for planning, similar to the national earthquake planning day in recent years (New Zealand ShakeOut – Get Ready).

Speakers at the Public Health Summer School pandemic symposium (from left): Professor Nick Wilson, Professor Geoff Rice, Professor Michael Baker and Dr Ryan McLane.

Will it happen again?

Typically there are several influenza pandemics per century, however none are known to have been as severe as the one in 1918/19. Although we now have access to antibiotics (to treat bacterial pneumonia that can occur after flu infection), there are concerns that in a sudden major pandemic there may be limits on how many sick people could be treated.

Besides the increased risk of rapid dissemination of new pandemic strains via mass movements of people with the growth of international air travel, there is also some evidence of increased emergence of new avian flu strains in recent years.

While mixing livestock in “wet markets” may have reduced in some parts of the world, there are still many places where pigs and poultry cohabit; or where these animals could potentially become infected with new flu viruses carried by wild birds. There is then potential spread of these new virus strains to humans.

“We also face the risk of pandemics from other diseases as we saw when Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) emerged,” Wilson says.

Similarly, Professor Raina McIntyre, from the University of New South Wales, refers to advances in synthetic biology and the risks of synthesised biological agents causing pandemics. This prospect might highlight the need for more generic pandemic planning that can address a very wide range of existing or novel diseases.

Speakers at the symposium noted how quarantine measures in 1918 may have sometimes helped prevent spread to Pacific Island countries, but also that the pandemic was probably already in Australia after maritime quarantine started. In a comparison study done with another island country (Iceland), Wilson noted successful use of travel restrictions in 1918 in this setting.

There are complex pros and cons around border control in the modern era, but Wilson argues that, for severe pandemics, the cost of border control for New Zealand (in terms of lost tourism revenue) might be outweighed by the benefits of saving many lives. Even if such border control subsequently failed, it could buy time to make further preparations for pandemic control.

”There are still some unresolved mysteries around the pandemic, such as the peak age of risk being young adults, the much higher male death rate, and the various reasons for the very much higher Māori mortality rate,” says Wilson. It is also a mystery why the usual pattern of higher death rates among poorer people has not been seen in New Zealand (in contrast to some other countries).

The researchers suggest that sustained investment in pandemic planning is an important means to mitigate the impact. Such central government activity needs to be complemented with building community resilience at the local level. “Preparing for our next pandemic or other natural disaster is just one more good reason for getting to know your neighbours,” says Baker.

Memorial reminders

Professors Wilson, Baker and Rice have all researched New Zealand public memorials relating to the 1918 pandemic and found only seven in the entire country. They suggest that memorials can be useful reminders of the threat of future pandemics, and can provide a focus of school field trips and other events.

- Watch Professor Geoffrey Rice's presentation

- Find out more about the Public Health Summer School