Unsung scientist

Dr Leopold Kirschner is one of those people who are much better known overseas than at home, but moves are underway to locally acknowledge his contributions to the University of Otago and to New Zealand.

Professor John Crump has described Leopold Kirschner as “one of Otago's most uncelebrated world-famous scientists”.

Crump, who is the McKinlay Professor in Global Health and a co-director of the Centre for International Health, is leading the charge to have Kirschner and his work more widely recognised.

Although Crump graduated from Otago and trained in infectious diseases and medical microbiology, he concedes that he only recently became aware that the international leptospirosis researcher L. Kirschner he had read about in the literature was the Leopold Kirschner who worked in a laboratory in the Hercus Building directly across Hanover Street from Crump's office.

“I couldn't help but feel that, given his contributions internationally and in New Zealand, he wasn't particularly well recognised,” Crump says.

Two people who knew Kirschner agree. Dr Elizabeth Whitcombe, who is an honorary research fellow in the Centre for International Health, as a child in Dunedin was acquainted with Kirschner and his wife, Alice, and has researched their backgrounds. Retired University of Otago virologist, Dr Terry Maguire, worked for Kirschner as a laboratory technician in the mid 1950s and has more recently given talks on Kirschner and his contribution to microbiology.

Kirschner's life before he emigrated to New Zealand in his late 50s was interesting to say the least. He was born to Jewish parents in the Polish part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire in 1889. He went to Vienna as a young man and saved enough money by working in a bank to study medicine. His studies were interrupted by service in the medical corps during World War One.

With the defeat and disintegration of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, Kirschner fled the political unrest and anti-Semitism of Vienna to Amsterdam to study at the Royal Tropical Institute, where the first leptospirosis reference laboratory in Europe had been established.

In the early 1930s, Kirschner joined the Pasteur Institute at Bandung on the Indonesian island of Java, then part of the Dutch East Indies. He was the deputy director of the institute, which was responsible for preparing vaccines and carrying out diagnostic services for 70 million people. While there, he undertook important work on the survival in the environment of the bacteria that causes leptospirosis, and he and a colleague developed an effective vaccine against plague, testing early versions on themselves.

Leopold and Alice, a gifted Viennese violinist, were interned following the Japanese invasion of Java in 1942. Leopold entered the camp with a hat stuffed with sulpha drugs and a belt laden with money, which he bartered for extra food for fellow internees. He put his medical expertise to good use in appalling conditions, caring for internees and making yeast cakes to provide scarce vitamins. The Japanese let him do laboratory tests and he concealed in a corner labelled “highly infectious material” a radio for listening to the BBC.

Kirschner was one of several distinguished overseas scientists – including Jewish refugees directly from Central Europe – the dean of the Medical School, later Sir Charles Hercus, recruited from the late 1930s to work in research units at Otago.

“Their medical qualifications, which were from the best schools of Europe, were not recognised by the Medical Council,” Whitcombe explains. “So Charles Hercus was very clever: he went to the Medical Research Council and set up research units with these people in charge.”

When the Kirschners arrived in Dunedin in 1946, Hercus appointed “Poldi”, as he was affectionately known, to head the Microbiology Research Unit.

It would have been easy to assume that Kirschner's decades of research on leptospirosis were over. New Zealand was thought to be free of the bacteria that causes leptospirosis, which is transmitted from other mammals to humans through direct contact with urine, or with urine-contaminated water and damp soil. It enters the body through cuts and abrasions and the mucous membranes of the eyes, nose and mouth. It can cause anything from minor flu-like symptoms to death.

From his background in Europe and Asia, Kirschner suspected that some illnesses among the farming community were caused by leptospirosis. He discovered the bacteria in rats he trapped in Dunedin and in pig samples he collected from the Dunedin abattoir. He alerted hospitals and, in 1951, became the first person to confirm the presence of leptospirosis in humans in New Zealand, in samples taken from a dairy farmer. Kirschner's laboratory subsequently confirmed hundreds of other cases, most associated with farming, and identified the bacteria in dogs and cattle.

“His seminal papers were major historical milestones in understanding this disease in New Zealand and he became an internationally recognised and respected figure in leptospirosis research,” Maguire says.

“He was a very articulate person and was invited to speak on leptospirosis at numerous international conferences. New Zealand was very fortunate to have imported a world-recognised researcher such as Leopold Kirschner: in fact, he was recognised more internationally than he was here.”

Maguire was particularly upset when an article entitled “Fifty Years of Leptospiral Research in New Zealand – a Perspective” was published in the New Zealand Veterinary Journal in 2002 with none of Kirschner's pioneering papers rating a single mention.

“It is tremendously important for us to recognise and give due credit to those pioneers who have foresight and perseverance in the early study of any illness.”

Maguire is one of the scientists whose working lives Kirschner shaped. His two-year stint as a technician sparked his career as a respected virologist at Otago. “I personally gained from Kirschner's ability as the mentor of a green-horn technician and am eternally grateful for the solid grounding in bacteriology while working with him.” Others include one of Kirschner's students, Solomon Faine, a noted leptospirosis researcher and emeritus professor of microbiology at Monash University in Melbourne.

Respiratory and infectious disease physician Dr Mike Maze, from the Centre for International Health, has revived the Otago tradition of leptospirosis research. He recently became the first student to complete a doctoral degree at Otago on leptospirosis since Faine in 1958. Maze's thesis studied the impact of leptospirosis in Tanzania.

He says that leptospirosis remains an important problem today, with more than a million cases worldwide and an estimated 60,000 deaths each year due to leptospirosis. In New Zealand there are around 200 notified cases annually. Early use of antibiotics is the best treatment, but the infection is difficult to diagnose.

Maze proffers that widespread vaccination of livestock and a predator-free New Zealand that removed other sources such as rats, mice and opossums might make eradication potentially feasible in New Zealand, but he says that leptospirosis is here to stay on a world stage.

As for Leopold Kirschner, he has received some recognition for his pioneering work. A major bacterial species causing leptospirosis, Leptospira kirschneri, has been officially named in his honour.

Crump, Whitcombe, Maguire and Maze would like to see wider recognition. Crump suggests that at the very least there should be a plaque put up, or a room or a laboratory named after the underknown scientist, who died in Dunedin in 1970, aged 81.

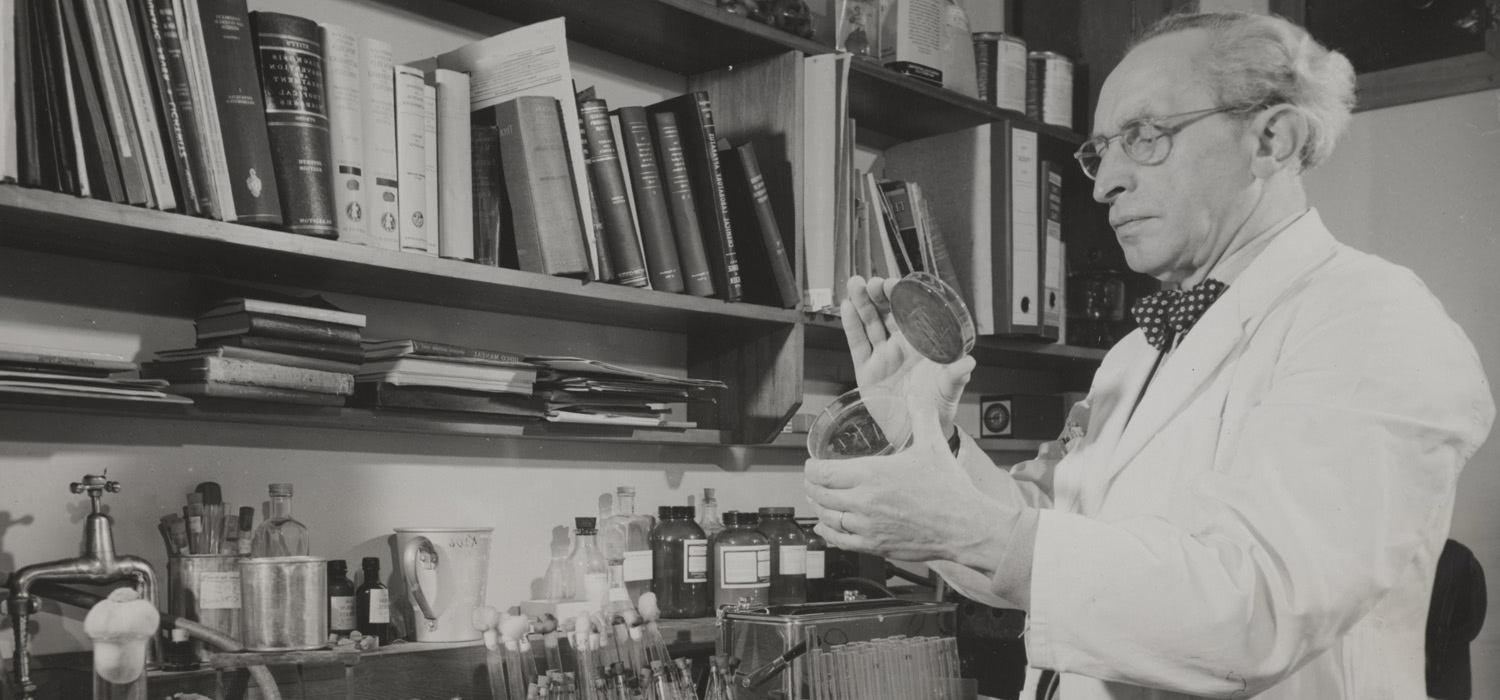

IAN DOUGHERTYBanner: Dr Leopold Kirscher 1949. Prime Minister's department photograph, Box-184-117, Hocken Collections - Uare Taoka o Hākena, University of Otago