Feature

'Game-changing' work recognised

The Christchurch Heart Institute has changed the way heart failure is treated here in New Zealand and internationally. It is a world leader in the development of diagnostic tests, treatments and the understanding of risk factors for heart disease. This work has been acknowledged with the presentation of the University's Research Group Award.

A patient is rushed to the emergency department with an alarming shortness of breath. At most hospitals around the globe they will likely get the same simple blood test. The test determines if they are experiencing heart failure and is the result of a ground-breaking discovery by a Christchurch research group.

In the 1990s the Christchurch Cardioendocrine Research Group was the first to discover that hormones in the blood can diagnose heart failure. Specifically, after years of research with emergency department patients they proved the hormones B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP) and pro B-type natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) are highly sensitive and specific tests for heart failure. Tests for both hormones are now used widely and are endorsed by all authoritative international bodies as guidelines for heart-failure diagnosis, prognosis and management. NT-proBNP is now the single-most widely-used blood test for heart-failure diagnostics globally.

Since these early breakthroughs the group has discovered and patented scores of other hormones for use in medical tests and has established a commercial company to market them. Renamed the Christchurch Heart Institute (CHI), the group now numbers around 50 staff and students, including cardiologists, geneticists, biochemists and physiologists, and has become a world leader in all aspects of cardiac research, including developing new treatments and understanding genetics to explain why heart disease runs in families.

In 2020 the Christchurch Heart Institute was awarded the University of Otago Research Group Award. It is the highest honour given by the University to a research group and recognises their success at improving patient outcomes and clinical practice globally.

CHI director Professor Mark Richards says, “our international leadership in this field for more than a quarter of a century reflects high quality research – translated from basic through to clinically-applied research ¬– conducted on the boundary between the disciplines of cardiology and endocrinology.”

He attributes the foundation of this success to three Canterbury-based clinicians back in the 1980s – cardiologist [Professor] Hamid Ikram, endocrinologist [Emeritus Professor] Eric Espiner and cardiovascular endocrinologist [Emeritus Professor] Gary Nicholls. Working at Princess Margaret Hospital, they debated how the body regulated salt and water levels – crucial to heart health – and hypothesised a peptide hormone was likely involved.

“Fortune favours the well-prepared and because of Hamid, Gary and Eric we were well-placed when ANP (a peptide hormone) was discovered and tested in rats. Gary got hold of some ANP and we injected it into ourselves,” says Richards. “Lo and behold, we had a big spike in sodium in our urine, showing it seemed to work in humans as it had done in rats. We didn't know how to measure ANP at that stage and later realised we had given ourselves what was a sledgehammer blow of peptides to completely non-physiological levels. But we were fine – and pleased with our results.”

The team began a concerted programme of research focused on ANP's – and then BNP's (another peptide hormone in the same family) – potential as a blood test. During the 1990s they studied emergency department patients and discovered NT-proBNP, a hormone in the same family, and subsequent clinical research studies provided its usefulness as a fast and accurate test for heart failure. The group's compelling evidence on NT-proBNP's clinical usefulness led to the development of the blood test now used in emergency departments worldwide.

“Before the discovery of NT-proBNP there was no blood test for heart failure. It was entirely clinical and the error rate was roughly 50 per cent – thankfully in over-diagnosis mostly, as people erred on the side of caution. Our test made a big difference globally.”

Richards says the next step was to investigate the cardiac hormone's usefulness in ongoing treatment. “We found that if your NT-proBNP levels were over a certain threshold your risks over the next 130 days were considerably worse than if you had a lower level.”

CHI Research Professor Vicky Cameron says the group's ground-breaking work in the 1980s and '90s gave them an international platform to build on.

“We are exploring how genetics alter people's risk of developing heart disease and may influence their outcomes once they have developed it.”

“The BNP story had a major impact and changed how people diagnose and treat heart failure – and, to some extent, heart attack – in New Zealand and internationally. It put New Zealand and the Christchurch Heart Institute on the global research map.”

In the past two decades the group has widened its focus from test development to understanding risks, developing new treatments and understanding what predisposes certain people to develop heart problems or suffer worse outcomes. Richards says this ongoing success is a result of the interdisciplinary co-operation between the sub-groups in the CHI. It is typified by good clinical recruitment and patient characterisation, expert cardiac imaging by cardiologists, accurate follow-up by research co-ordinators, the development and reliable conduct of immunoassays for blood biomarkers by peptide biochemists, and genotyping by genetics investigators.

The genetics of heart disease are one area of strength, says Cameron. “We are exploring how genetics alter people's risk of developing heart disease and may influence their outcomes once they have developed it.”

By fostering international collaborations the CHI now has access to the biological samples and patient records of almost three-quarters-of-a-million heart disease patients from New Zealand, the United States and the United Kingdom.

“Our understanding of an individual's risk of developing heart disease over their lifetime and the role genetics play requires 'big data' to see changes in large groups. For example, we showed in a relatively small group of around 2,000 New Zealand patients that the genetic marker most strongly linked with risk of having a heart attack did not affect the patient's subsequent lifespan. This finding led to an invitation for us to join a large international consortium where we were able to convincingly show the same effect in around 250,000 patients.”

Cameron says the CHI has established a number of large community studies in New Zealand that track the progress of different groups at higher risk of developing the disease. One of these is the Hauora Manawa study which compares the heart health of Māori from rural and urban centres, and non-Māori.

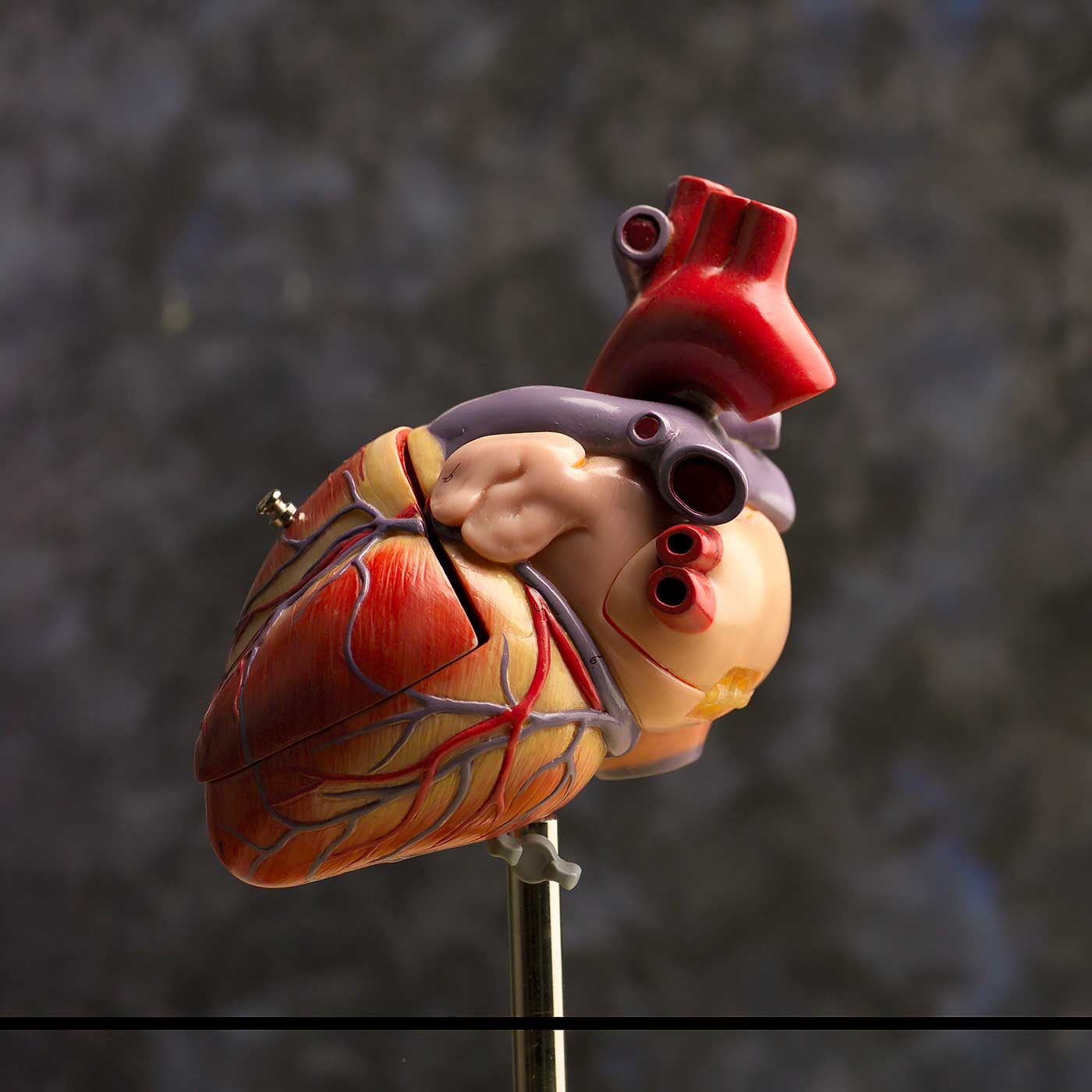

The Christchurch Heart Institute comprises a multidisciplinary team of experts in fields including cardiology, genetics, biochemistry and physiology.

Another, the Pasifika Heart Study, aims to understand how the risk profile of South Island-based Pacific Islanders differs from those living in Auckland. In the Canterbury District Health Board area, for example, Pacific people's rate of dying from heart disease is 1½ times greater than other population groups, highlighting the need to understand the impact of lifestyle changes and how the Pasifika genetic make-up contributes to poorer outcomes.

Cameron says the CHI has also developed a group of more than 3,300 “healthy volunteers”. These are people recruited because they do not have heart disease and whose progress through life – and any development of heart disease – is being tracked to understand differentiating factors such as lifestyle and genetics.

CHI clinicians have worked hard to develop and fine-tune treatments for different types of heart disease, says Cameron. Over the years their large clinical trials have shown the success of NT-proBNP in guiding the treatment of patients after they develop heart failure. The test and treatment strategy they have created has been proven to reduce death in heart-failure patients aged under 75 by 35 per cent, compared with the previously-used clinical treatment regime. This strategy, where treatment is guided by NT-proBNP levels, also reduces heart failure and cardiovascular hospitalisation by 20 per cent regardless of age.

The team's clinician researchers are exploring how to maximise the effects of medication for different forms of heart disease and new ways of detecting heart disease, including through the use of CT which could broaden access to fast and accurate diagnosis to those in areas outside main centres and away from tertiary hospitals.

Developing new tests, or biomarkers, for different types of heart disease continues to be an important part of the research group's activities. A commercial company, Upstream Medical Technologies (which has the University of Otago as a key stakeholder), has been established to commercialise the CHI's discoveries in an international market worth billions of dollars. The tests are predominantly for different types of heart disease, including unstable angina for which there is currently no reliable test.

Other CHI members are investigating CNP, a hormone in the same family as BNP, and its potential to help those with congenital growth issues.

Cameron says one constant through the years has been the group's engagement with the community. In the past decade alone they have given hundreds of talks to groups, explaining what they found in their studies and how this impacts on people's health and disease. The group also hosts work-experience for high school students with an interest in health science and, where possible, shares stories of their success with media.

“CHI researchers feel incredibly privileged to have contributed to discoveries that have made a difference in clinical practice in Aotearoa and globally. That is why we feel it is important to share what we have learnt with the general public, who are those who fund our research, participate in it and, ultimately, can benefit from it.”

KIM THOMAS