In 1893 New Zealand became the first self-governing country in the world to grant women the right to vote in parliamentary elections. By this time, however, a young teacher, Caroline Freeman, had already broken new ground for women at the University of Otago.

In 1878 Caroline Freeman was the first matriculated woman to enrol at the University and her graduation with a Bachelor of Arts in 1885 was marked as a celebration of the new educational opportunities for her sex.

Further firsts for women came quickly. In 1891 Emily Siedeberg became Otago's first female medical student and New Zealand's first female medical graduate in 1896. A year later she set up private practice in Dunedin and became a role model for generations of young women who followed her.

In 1893 another extraordinary young woman, Ethel Benjamin, became the first woman to be admitted to Otago's law school (indeed, the first in Australasia). An outstanding student, she graduated LLB in 1897 making the first official speech by a woman at the University.

Between 1885 and 1900, a total of 58 women graduated from the University of Otago. And, in 1929, yet another woman attained a significant milestone for her people: Kathleen Anneui Pih (later Pih-Chang) became the first person of Chinese descent (male or female) to graduate with a medical degree in New Zealand.

All of these women were determined high achievers, many of whom succeeded against the odds.

Banner images (from left): Ethel Rebecca Benjamin, 1897, Box-005-001. Caroline Freeman, Steffano Webb photographer, P2017-009. Dr Emily Siedeberg (later McKinnon), 1896, F.L. Jones photographer, Box-148-002. Hocken Collections Uare Taoka o Hākena.Today

Today females comprise almost 59 per cent of the University's student population and women scholars excel across all academic disciplines.

1

The power of the purse

Professor Barbara Brookes: “We need to provide the power of the purse for all citizens to fully meet the aims of the suffragists.”

Professor Barbara Brookes: “We need to provide the power of the purse for all citizens to fully meet the aims of the suffragists.”

Money matters: it always has – especially for women.

Professor Barbara Brookes argues that, while gaining the right to vote in 1893 was a seminal moment in history for New Zealand women, gaining “the power of the purse” might be just as important.

Kate Sheppard is most well known for leading the successful fight for women's suffrage 125 years ago. However, Sheppard was also deeply interested in economic independence, naming “work and wages” as the top priority at the Canterbury Women's Institute in January 1893.

As a historian who has researched and written extensively about New Zealand women's history, Brookes argues that money – “a seemingly neutral object” – was historically gendered and that this has had significant implications for women's lives.

“The wife's role was to manage the home on the housekeeping allowance, and, as late as 1950, a judge in the Supreme Court ruled that a wife must pay back to her husband any money saved from her housekeeping allowance.”

Kate Sheppard had asked why a married woman was classified as her husband's dependant “for she earns a living, in many cases more hardly than her husband does, although he is the actual wage receiver”. In response, the National Council of Women proposed that a wife should be entitled to a portion of her husband's earnings for her own use but, according to Brookes, this seemed even more contentious than women's suffrage.

“This was 1896 and considered outrageous – a social revolution likely to shake the very foundations of society. Newspapers claimed it would degrade women from a position as equals to that of paid housekeepers, destroying the family 'community of interest' and, even worse, that women would be paid for exercising the sacred function of motherhood.”

She says this “community of interest” in marriage – in which men were the breadwinners and women the dependents – continued into the late 20th century.

It had implications for wages: women were routinely paid less than men. It also had implications for access to credit, for superannuation schemes, for women's capacity to support their children and to leave a marriage.

For example: in 1904 a male assistant teacher earned £175, while his female counterpart earned £97; women clerks in the Post Office were paid three-fifths of the male rate; and, in the boot and shoe industry, women making boots were classified as assistants rather than apprentices ensuring a lack of career progression and lower wages. In 1911, when the Old Age Pension was set at £26 per year, a widow with one child received £12 per year, with £6 for each extra child up to four children. From 1926 to 1945, Māori old age and widows' pensions were routinely paid at 25 per cent less than pensions to Europeans.

Brookes quotes a response from Woman's Weekly agony aunt Dorothy Dix to a question about the propriety of a married woman working during the Depression. “The reply was that women should only work outside the home in cases of dire necessity: if a woman 'humiliated' a man by working 'it will develop an inferiority complex in him that will wreck him …'

“The wife's role was to manage the home on the housekeeping allowance, and, as late as 1950, a judge in the Supreme Court ruled that a wife must pay back to her husband any money saved from her housekeeping allowance.”

Women increasingly entered the workforce during the buoyant post-war years; the baby-boom generation poured into secondary schools; and the numbers of women accessing tertiary education were growing.

Māori were also moving to the cities: by 1951, 20 per cent of Māori women were recorded as in paid work, compared to only around 12 per cent in 1926.

By 1971 nearly 40 per cent of women aged between 15 and 64 were working, and married women made up half of those. However, Brookes says, they were still employed in a narrow range of occupations – disproportionately represented in unskilled jobs and notably absent from senior positions. “The Equal Pay Acts of 1960 and 1972 had not led to revolutionary change.”

Some change had come with family allowances paid directly to wives: the means-tested Family Allowance (1926) and the Universal Family Benefit in 1946 set at 10 shillings a week per child (about $40 in today's terms).

“This was significant. Women appreciated a benefit paid directly to them: it gave them a sense of empowerment and, from 1958, families could capitalise the benefit to enter the housing market. In a 1980 survey of women, 60 per cent of respondents cited the Family Benefit as their main source of income.”

It was a particularly significant innovation for Māori women with large families. “Previously unregistered births were quickly registered and marriages formalised to meet requirements.”

However, in Māori families the “community of interest” included the wider whānau: income was shared. “Who earned the money made little difference, whereas in Pākehā families women were often reluctant to spend money earned by the 'male breadwinner'.”

The introduction of the Domestic Purposes Benefit in 1973 which, while widely contested, made it possible for some women to leave violent marriages, and the Muldoon government's universal national superannuation scheme gave women the same entitlement as men at the age of 60. “For the first time in their lives many married women did not have to ask their husbands for money.”

The 1977 Human Rights Commission Act aimed to abolish discrimination on sex, marital status, race, colour or ethnicity, but Brookes says convention continued to rule rather than law. “Women have told me that even in the early '80s they required their husband's or a male relative's signature to buy items on hire purchase or to take out a loan. In some families wives did not even know how much their husbands earned.”

The challenge for women continues, says Brookes. “Feminists have fought for individual rights and individual access to money. Some are now doing very well: those with tertiary education may have professional jobs and some have high incomes. But others are doing very badly – and they are usually not Pākehā.

“Women fought for citizenship in 1893. They hoped to bring into being a morally principled nation, committed to justice and equality, which would see all women as full participants in social and political life. Today, I suggest, we need to provide the power of the purse for all citizens to fully meet the aims of the suffragists.”

2

Small scale: big success

Dr Carla Meledandri: “Pushing the boundaries of fundamental research is vital – taking what we have found and applying it to solve problems follows on.”

Dr Carla Meledandri (Chemistry) is using some of the world's smallest particles to tackle some of the world's largest problems – from dental decay to climate change.

Her expertise in nanoscience, working at a scale of billionths of a metre, helped win her the 2017 Prime Minister's MacDiarmid Emerging Scientist Prize, the latest in a series of research awards.

Interdisciplinary collaborations with the Faculty of Dentistry have enabled the development of new materials designed to treat some of the causes of oral disease rather than the symptoms, hopefully leading to reduced costs and improving health worldwide.

“We are currently in discussions with existing dental manufacturing companies with the aim of establishing partnerships to generate revenue, attract further investment and develop products that could go far beyond filling materials.”

Meledandri and Dental School associate dean Dr Don Schwass have demonstrated new ways to deliver and maintain antibacterial effects in the oral environment during dental treatment by using silver nanoparticle technologies.

They succeeded – winning an Otago Innovation Proof of Concept Award – with a colloid suspension containing silver particles. The suspension, designed for dentists to apply after drilling and before filling, was later licensed to overseas developers.

Subsequent work produced a gel containing silver nanoparticles that could be injected around a tooth or implant to deliver the antimicrobial particles to otherwise hard-to-reach areas prone to infection, such as gingival and periodontal pockets.

Early implant experiments with animals at Invermay's AgResearch, led by Professor Warwick Duncan, head of Oral Sciences, saw Meledandri venturing outside the comfort zone of her laboratory. “As a chemist I found myself doing things you don't expect to do, such as having my hands inside a sheep.”

There were more new experiences for the team trying to share successful science with the real world.

“The feedback from industry on the science was positive, but it was when we began designing technologies that could be classified as a medical device rather than therapeutic, which is an easier pathway to regulatory approval, that investors really became interested.”

Meledandri's team bonded silver nanoparticles within a dental filling material where they have a surface effect, preventing the growth and adhesion of bacterial biofilms, a significant source of filling material failure.

With this new product, Meledandri and her colleagues set up a new company, Silventum Limited, to commercialise and further develop their research.

“We are currently in discussions with existing dental manufacturing companies with the aim of establishing partnerships to generate revenue, attract further investment and develop products that could go far beyond filling materials.”

Meledandri, who won the Norman F.B. Barry Foundation Emerging Innovator award in 2016, is also a principal investigator in the MacDiarmid Institute for Advanced Materials and Nanotechnology, a Centre of Research Excellence in which New Zealand's leading scientists work together to solve problems using materials science and technology.

Through the MacDiarmid Institute, Meledandri was invited by Professor Shane Telfer (Massey University) to join an international group working on using porous materials known as metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) to capture harmful gases, with funding awarded by the Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment.

“It's very early days, but it's an area that has huge potential. Many scientists all over the world are looking at new ways of using MOFs both to store environmentally friendly gases and in ways to combat climate change.

“The pores in MOFs can be designed to be the same size as certain gas molecules, including carbon dioxide, which enables CO2 capture from smoke stack emissions, and hydrogen or methane, enabling fuel storage. As MOFs are mostly free space, they have the potential to absorb and store large volumes of gases though, in practice, the most interior pores can be difficult to access.”

Meledandri's Otago team is looking at preparing bespoke MOF structures, designed by Telfer and other team members – but on the nanoscale, where unique physical properties emerge that can cause materials to behave in unusual ways.

“Nanoscale MOFs have significantly increased surface area and pore volume, with the majority of the pores located at the surface, rather than the interior, of the material where they can be easily accessed by gas molecules. They offer a greater potential to reach the full storage capabilities of the material. We're aiming to obtain better gas uptake and we're also finding that we're creating a wide range of interesting pore structures along the way that would be an additional improvement on existing materials.”

Research has already indicated that working at the nanoscale is producing surprisingly positive results.

“Some interesting things are happening that we are still trying to understand fully, but considering that it's still early days for us, our results have been much better than expected. We have also been able to demonstrate that we can tune the surface chemistry of the nanostructures, which could enable us to easily incorporate the nanoscale MOFs into other materials such as gels or plastics or porous membranes.”

Once successful, the idea is to work with team members at Australia's Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO) to see if the flow chemistry technology used in Meledandri's lab can be scaled up to industrial size, which could give science new tools for ameliorating climate change, both by reducing further greenhouse gas emissions and capturing existing atmospheric carbon dioxide.

Meledandri is also collaborating with Otago Chemistry Professor Sally Brooker, an expert in molecular magnetism. Brooker has developed single molecule magnets with interesting properties in solution, but is working with Meledandri to robustly attach these molecules on nanosurfaces as a step towards developing improved magnetic storage devices.

Meledandri won a Fast-Start Marsden Research Grant in 2011 to support her early research into the synthesis of shape-controlled magnetic nanoparticles, followed by an Early Career Award for Distinction in Research.

Now she is using her recent Prime Minister's prize to help fund her own team's research. “I never expected to win, so, when I received the call, it was an absolute, complete surprise. I couldn't believe it. Then I had to keep it quiet, even from my own research group, who had done all the hard work.

“They are such a good group to work with, so not being able to share the success with them from the start was hard. But now the prize allows me to bring new people into the lab and develop new ideas.

“Pushing the boundaries of fundamental research is vital – taking what we have found and applying it to solve problems follows on. We use both fundamental and applied research in mutually beneficial ways to get results. We usually go back to the fundamentals to address questions that arise from applications. It works both ways and that is really important.”

Funding

Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment

The MacDiarmid Institute

University of Otago

Otago Innovation Limited

Prime Minister's Emerging Science Prize

3

'Re-animating' environmental law

Associate Professor Ceri Warnock: “Environmental disputes require us to predict the future rather than determine the past; they can affect many people … and significant uncertainty abounds.”

Associate Professor Ceri Warnock (Law) has challenged scholars, politicians and professionals to ponder the impact of environmental law on traditional understandings of law and wider constitutional principles.

Warnock says that law plays a critical role in solving environmental problems, but employing traditional legal structures is tricky.

“Adjudicatory bodies will be accepted by the community if they are bounded by law, but not straightjacketed by concepts developed in other areas of law.”

She argues that the complex nature of environmental issues means that trying to resolve them in a theoretical or artificial world in which abstract rules are laid down in advance seldom works: something she says that scholars critiquing resource management law and politicians proposing amendments forget at times.

“Environmental disputes require us to predict the future rather than determine the past; they can affect many people, including future generations; they can impact the environmental, socio-cultural and economic realms; and significant uncertainty abounds,” Warnock says.

“A classic conception of the rule of law prioritises certainty and predictability: clear rules set down in advance that tell us what we can and cannot do. But in the environmental context, enacting pre-determined law that establishes clear legal rights and responsibilities, while maintaining sharp delineations between law, policy and facts, proves challenging.

“One response of governments has been to set general directions and standards, and to then create power maps, allocating problem-solving roles to downstream bodies such as specialist environment courts.

“In this context, adjudicatory bodies will be accepted by the community if they are bounded by law, but not straightjacketed by concepts developed in other areas of law,” Warnock maintains.

“Rather, they must have sufficient procedural flexibility to respond to the nature of environmental problem-solving and encourage the participation of impacted parties.”

Warnock acknowledges that some commentators have described environmental law as more like politics than it is like “proper” law.

She responds that, rather than straying from core legal principles such as the rule of law, environmental law is “re-animating them by peeling back ideological layers”, and responsive problem-solving institutions such as the New Zealand Environment Court that encourage participation are essential components in that re-animation.

She argues that, when politicians seek to reduce possibilities for participation in the name of reduced costs and faster decisions, as happens from time to time, they actually take us further away from the rule of law in an environmental context.

Warnock adds that the New Zealand Environment Court has been looked at as the model for the proliferation of specialist environment courts around the world over the past decade.

Warnock was awarded the country's premier legal research award, the New Zealand Law Foundation's International Research Fellowship, based at Oxford University, to undertake the first comprehensive legal analysis of the Environment Court.

This led to her being invited to deliver the prestigious Salmon Lecture in 2018, an annual public lecture on environmental law run by the New Zealand Association of Resource Management and named after a former high court judge, Peter Salmond QC.

Funding

New Zealand Law Foundation International Research Fellowship

4

Diversity or tokenism?

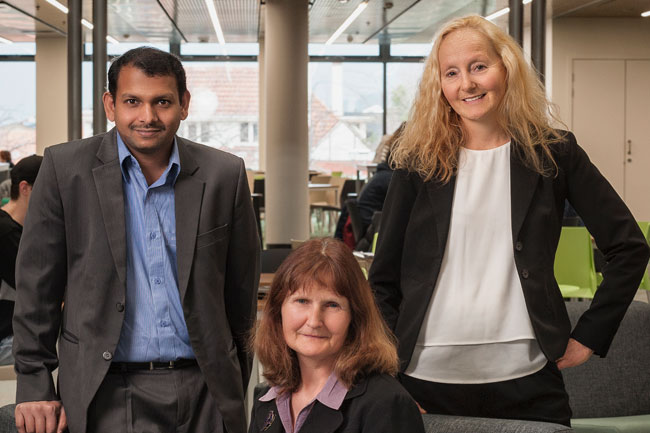

Dr Pallab Biswas, Associate Professor Ros Whiting and Dr Helen Roberts: “It's not simply a matter of having female representation, it's accepting the range of perspectives and skills that increased diversity on the board contributes.”

It's all very well to have targets or quotas for female representation on boards, but their voice also needs to be recognised for any benefits to be realised.

A University of Otago study of Asian businesses found evidence of tokenism, where women were represented on boards, but did not have a voice nor influence.

Otago Business School Accountancy and Finance researchers Associate Professor Ros Whiting, Dr Helen Roberts and Dr Pallab Biswas have studied the role of women in governance in businesses across Hong Kong, South Korea, Malaysia, Singapore and Bangladesh.

In 2011 Malaysia set a target of 30 per cent female board representation by 2016, and by 2017 it had an average of 19 per cent of board positions held by women. But while it has made good progress (up from eight per cent in 2011), the Otago study suggests cultural and ethnic restraints have limited the true influence of the women.

"A lot of the research on women in governance is coming from the United States, so it's useful to understand in some depth what the barriers are to women in business from other cultures and what effect that, in turn, has on business."

Many of the businesses studied in Bangladesh were family-owned and had a traditional patriarchal approach. Female representation was often the wife or daughter of the owner, and her contribution was not always sought, listened to nor acted on.

The researchers concluded forcing female director appointments or mandating gender quotas can reduce a firm's performance in countries with strong cultural resistance.

"A lot of the research on women in governance is coming from the United States, so it's useful to understand in some depth what the barriers are to women in business from other cultures and what effect that, in turn, has on business," Whiting explains.

"Understanding the barriers means we can look at what is needed to not only encourage women to seek positions on boards, but also for their ideas to be heard. It's not simply a matter of having female representation, it's accepting the range of perspectives and skills that increased diversity on the board contributes.

"Often as managers of the household, women bring an excellent perspective of consumer needs to the table, for instance."

There are benefits in board diversity that are common across different cultures. Research has, for instance, shown taking note of different points of view and aligning the organisation with its clients helps to improve business sustainability.

While New Zealand fares better than Australia's statistics on women's role in governance, there is growing concern here about the lack of women in senior levels and governance, including in partnership in the accounting professions.

A study by Whiting with colleagues in Australia and Scotland confirms a glass ceiling still exists for females in the accountancy profession. While there is an increasing number of women in the accounting profession, they are not becoming partners – currently they make up between 10 and 25 per cent of New Zealand Big 4 firms' partners.

This research has pinpointed stereotypical discrimination, workplace structural barriers and employee preferences are barriers to female progression to partnership level.

Not only is there covert gender bias from some professional accounting firms making the partnership decisions, women often don't put themselves forward because of the long-hours culture and perceptions about 24/7 availability to clients.

Whiting suggests a supportive company culture and also home environment are the keys to change.

Funding

University of Otago

Scottish Accountancy Trust for Education and Research (SATER).