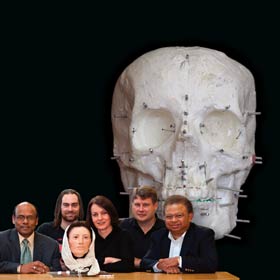

From left to right: Professor I Premachandra, Anatomy Museum preparator Shane Soal, Louisa Baillie, Neil Waddell and Dr George Dias with the rebuilt face of a 2,500-year-old Anatolian peasant. They hope their techniques could ultimately have modern-day legal applications.

Resurrecting the dead may be impossible, but Dr George Dias is achieving the next best thing.

He and his multidisciplinary team are breaking new ground in putting flesh on old bones, giving faces to ancient skulls and bringing history to life.

Dias (Department of Anatomy and Structural Biology) hopes his world-leading research may soon help solve modern mysteries too. The aim is to refine techniques of rebuilding faces from skulls to the point where the results may be used as identification in court cases. Dias has a background in dental and maxillofacial surgery, reconstructing damaged faces. However, he's wary of the term reconstruction when it comes to his archaeological and forensic research on skulls. “I'd prefer to use the term facial approximation – it's nowhere near a reconstruction at this stage.”

But the process is certainly a painstaking anatomical construction, layering muscles, blood vessels and skin over bone to reveal a face – and it's one that Dias's team has refined considerably since the first attempts.

Initially Dias responded to colleagues from the University of Coimbra, Portugal, asking for assistance to identify skulls from modern mass graves. They hoped to be able to gain identification if they could put faces to the dead.

Dias realised that the science of facial reconstruction had shortcomings, particularly as measures of soft tissue depths used in rebuilding were just averages, based only on racial groups, gender and body type – whereas every face was individual.

Dias realised that the science of facial reconstruction had shortcomings, particularly as measures of soft tissue depths used in rebuilding were just averages, based only on racial groups, gender and body type – whereas every face was individual.

He and Associate Professor I Premachandra (Department of Finance and Qualitative Analysis) together with postgraduate student Charlotte Oskam worked on a mathematical model to predict facial soft tissue depths based on skull measurements.

Work was initially on cadavers, but the latest research – carried out with postgraduate anatomy student Louisa Baillie – involves living people, with the intention of doing a blind reconstruction that the team can compare with reality.

Dias's team's first project, through the University of Applied Sciences, RheinAhrCampus, was to add a face to a skull to help German police try to identify a body. Although it was never identified, the experience helped with the second challenge – with Kunaal Sologar and Steve Swindells of the Faculty of Dentistry – giving life to the skull of a 2,300-year-old Egyptian mummy at the Otago Museum.

Both projects showed inadequacies in the methods used, so the team developed new techniques for their third face – that of a 2,500-year-old Anatolian peasant. The skull was found at an archaeological site in Turkey, run by Anadolu and Ankara Universities, which collaborate with Otago.

The team, including Baillie and Neil Waddell from the Dental School, used their new calculations to build tissue, adding more life-like eyes, real hair and silicone skin instead of sculpting clay, achieving improved levels of realism.

“The difference between us and a sculptor is that we work from the inside out, rather than the outside in,” says Dias. “We need to be anatomically correct and scientifically accurate.

“When we start, we have no idea what the person is going to look like – we show no bias – and it's almost eerie when the project suddenly becomes a face. You get an idea when the eyes and nose are done, but it's really only when the lips and the rest of the skin go on that the face reveals itself.

“It always fascinates me – you can't help but start to imagine what the face might look like – but it's always a total surprise and, when that happens, you can be sure that it's as close as you can get and you have not affected the outcome with bias.

“Within a few years we hope to develop the technology to a point where it can be used as an identification tool in courts.

“A number of people doing similar work are interested in our methods, but we still have a lot of refining to do. It's multidisciplinary research – you can't be in a cocoon of your own and just do it all yourself.”

Funding

University of Otago (Department of Anatomy and Structural Biology, Faculty of Dentistry)