Researchers explore seaweed's

untapped

potential

Research into macroalgae or seaweed goes back 140 years at the University of Otago, but it has never been more relevant than it is now as a new generation of researchers examine the potential of these prolific marine plants in future food production, as a carbon sink and in mitigating intensive farming impacts in both the sea and on land.

The co-director of the Otago-based national Centre of Research Excellence (CoRE) Coastal People: Southern Skies (CPSS), Associate Professor Chris Hepburn (Marine Science), says rebuilding healthy and productive coastal ecosystems and creating new marine industry is a one of the key challenges for a small island nation in the midst of the planet's largest ocean.

“Seaweed research is now mainstream and we have the opportunity to explore the untapped potential of one of the world's largest aquaculture industries. New Zealand's diverse macroalgal flora and our productive and extensive exclusive economic zone offer huge opportunity for this environmentally beneficial industry.”

This sits well with the CoRE's vision of flourishing wellness, or mauri ora, of coastal communities and its mission to connect, understand and restore coastal ecosystems through transformative research, local action and by unlocking potential by utilising new pathways to learning.

Hepburn says seaweed aquaculture is low impact and can provide a source of high-value food, animal feed and bioenergy. It can also play a vital role in bioremediation – absorbing excess nutrients that make their way into coastal waters, providing food and habitat for a wide range of marine species, and even acting as a carbon sink.

Researchers examine seaweed beds in the Otago harbour.

“Southern New Zealand provides a particularly favourable environment. Our cooler nutrient-rich waters provide the perfect conditions for seaweed growth.”

Hepburn says that their focus has moved beyond sustainability to rebuilding and that means reseeding, habitat restoration and stopping fishing to allow stocks to recover.

“Our CoRE is really connected to forward-facing environmental restoration. But we can't restore to what was, we need to restore for what will be.”

This means encouraging industry that provides an environmental benefit and making marine ecosystem restoration as commonplace as restoration of terrestrial habitats, along with building integrated management of the land and sea.

“Ki uta ki tai, from the mountains to the sea,” adds Hepburn.

“We've moved beyond thinking about sustainability in the marine setting. Our focus has to be on rebuild.”

“Tending the sea like a garden and not exploiting marine natural resources like a mine is ingrained in many indigenous cultures and a central aspect of kaitiakitanga.”

Associate Professor Chris Hepburn

“A lot of these industries are forward facing and are also dealing with some of the actual issues that are facing New Zealand, such as addressing agricultural emissions.”

Working with zero-methane agriculture company, CH4 Global, Otago researchers have supported Jim Barrett, an innovator in the aquaculture industry, to establish a trial research farm for the seaweed Asparagopsis armata in Big Glory Bay, Rakiura.

This species, when used as an animal feed supplement, has the potential to reduce up to 90 per cent of methane emissions from ruminant animals, which make up more than 30 per cent of New Zealand's greenhouse emissions, compared to about 20 per cent from transport.

This work has also provided an exciting opportunity for new, young researchers such as MSc student Will Pinfold to do hands-on work with leaders in an emerging industry.

An aquaculture array is to be installed at the Portobello Marine Laboratory and will provide scalable solutions for future aquaculture. For example, developing low impact co-culture of seaweeds and other species such as fish and bivalves, and developing new technology for future offshore aquaculture installations.

Technology developed from aquaculture can be applied in restoring damaged marine habitats and rebuilding the base of high value fisheries.

Research funded by an MBIE Smart Ideas grant is developing ways to reseed lost kelp forests – the foundational habitat of productive and valuable coastal fisheries. Several young researchers, including PhD student Duong Le, are culturing kelp species sourced from around New Zealand, conducting breeding trials and physiological experiments to develop a strain of climate change resilient kelp for reseeding in the long term.

Other innovative research involves investigating ways to turn invasive species such as Undaria pinnatifida (wakame), a native of Japan and Korea, into a resource.

More than 20 years of research at Otago is supporting the development of industry (food, stock food, plant growth promoters, high value compounds) around this high value species, while also controlling the spread of an invasive species that can damage native ecosystems. This work is supported by a range of research partners, primarily Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu.

Today this work is being carried on by a new generation of researchers such as PhD student Gaby Keeler-May who has been developing methodology to control Undaria.

“Controlling weeds on land is a common part of agriculture, but the idea that regular and active management is needed in marine habitats is meet with surprise. Tending the sea like a garden and not exploiting marine natural resources like a mine is ingrained in many indigenous cultures and a central aspect of kaitiakitanga,” says Hepburn.

Fundamental seaweed research also continues to build a broader understanding of the foundation of productive coastal ecosystems.

PhD student Namrata Chand is gathering important information on poorly understood red algal meadows. These meadows provide important habitat for many marine species, as well as ecosystem services such as carbon storage and nutrient cycling. Protection of habitat like this reduces the likelihood of eutrophication and unhealthy coastal waters.

“Our CoRE has a focus on early career researchers and I think there is a bit of a generational change happening right now. We need the energy and open minds of researchers to support coastal communities facing an uncertain future,” says Hepburn.

“We have many tools and types of knowledge available, we should appropriately apply these to the problems we face with great thought but without bias. With change comes the need to change how we think – change also brings opportunity. I think seaweed has a key role to play in how we restore and build new industry in our coastal oceans.”

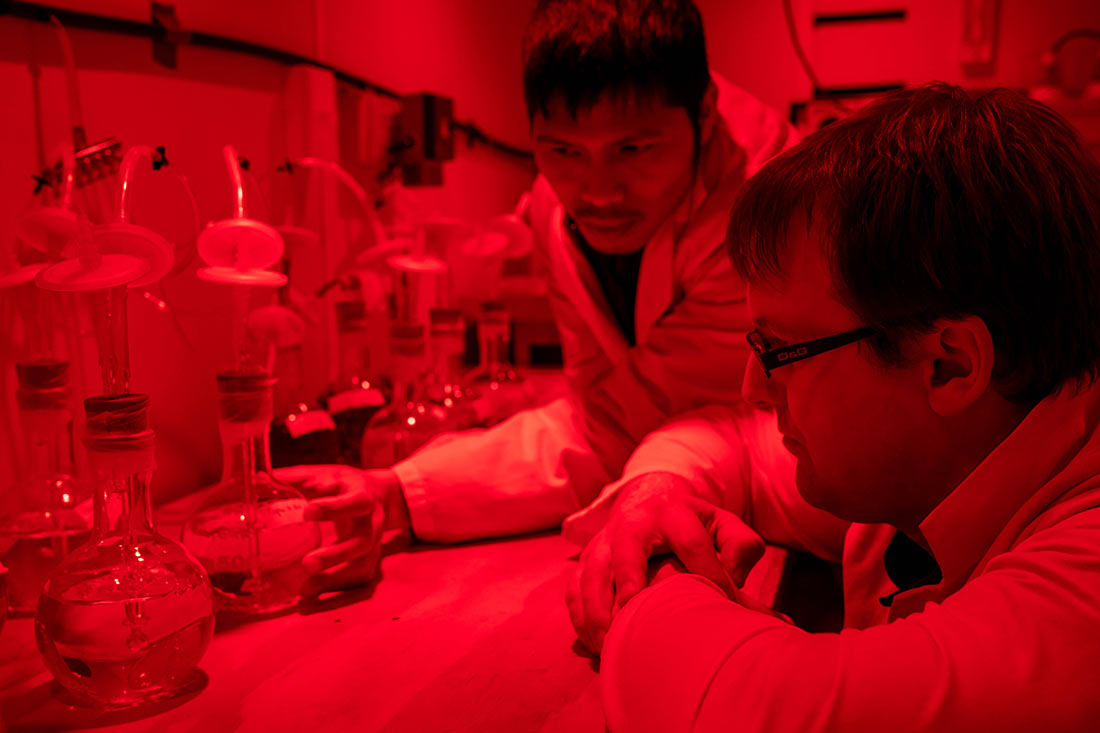

PhD student Duong Le and Dr Daniel Pritchard maintain cultures of kelp sourced from around New Zealand.

Otago's a long history of seaweed research dates back to 1881 when Professor T. J. Parker discovered sieve tube elements – a basic transport system similar to that of higher plants – in the giant kelp Macrocystis pyrifera.

More recently, pioneering work around the potential for kelp forests to buffer against ocean acidification was led by Professor Catriona Hurd in the Department of Botany.

With a sustained history of research focused on the taxonomy chemistry, physiology, ecology of our seaweed flora, Otago is now at the leading edge of this exciting field.

Funding

Tertiary Education Commission

Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu

CH4 Global

The giant kelp Macrocystis pyrifera.