Monday 8 January 2018 2:58pm

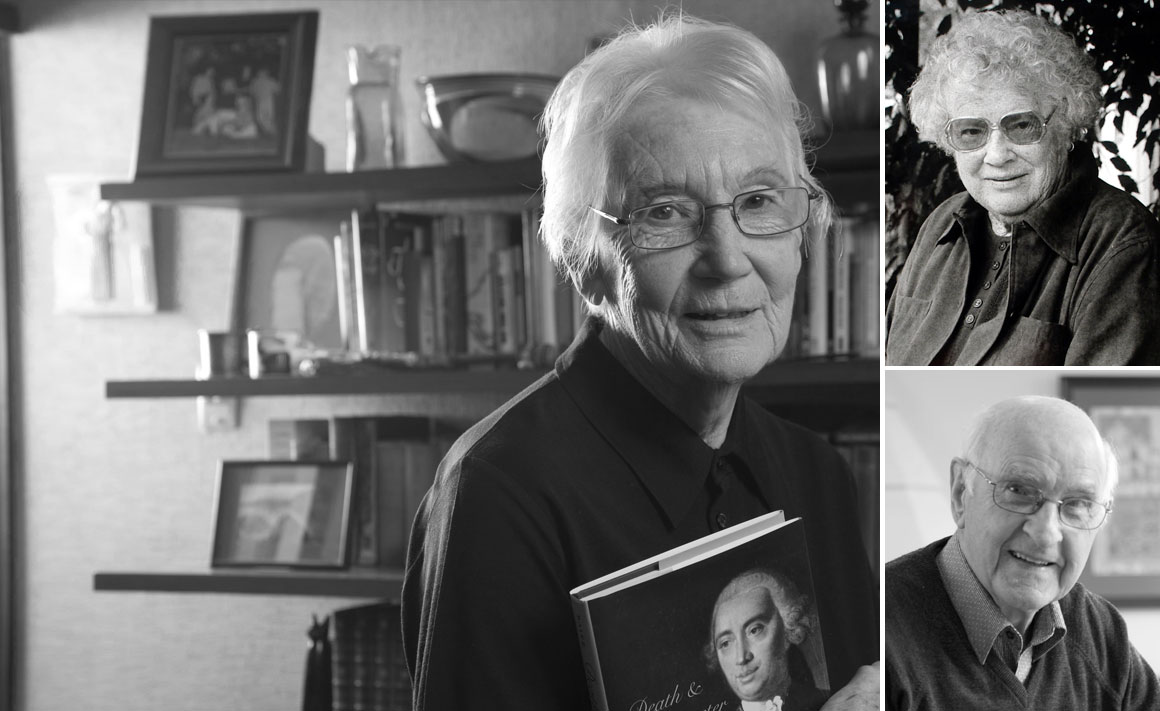

Monday 8 January 2018 2:58pmExhorted by the University's founders to “dare to be wise”, Otago alumni have, indeed, dared. They have questioned traditional norms, challenged us with new ideas and inspired us with their creative thought.

Internationally renowned moral philosopher Professor Annette Baier, for example, challenged accepted thinking about the way men and women make decisions about right and wrong, arguing that they do this based on different value systems. In 2007 she was included in an international list of Top 100 living geniuses by The Daily Telegraph.

“As knowledge changes, so you have to change your understanding,” said theologian Professor Sir Lloyd Geering, whose views on the resurrection and the immortality of the soul triggered an unexpected storm. He was famously tried for heresy, however the charges of doctrinal error and disturbing the peace of the church were ultimately dismissed.

For celebrated Otago writer Janet Frame, university was her refuge – a place to explore bold new ideas and revel in the expansion of her own mind. She described an “intense feeling of wonder at the torrent of ideas released by books, music, art, other people”. Frame was awarded the University's Burns Fellowship in 1965, received an Honorary Doctor of Literature degree, was nominated for the Nobel Prize for Literature, named an “icon” by the Arts Foundation of New Zealand and awarded the Prime Minister's Award for Literary Achievement. During her life she published 12 novels, four story collections and one book of poetry; a further collection of poetry and another novel were published after her death.

Today

1

Ethical sea change

Professor Lisa Ellis and Lauren Holloway: “If we stick with the status quo, adjustment to sea-level rise is going to exacerbate existing inequality. Nobody in New Zealand wants that.”

Potential responses to the risks of sea-level rise range from “it's your place, it's your problem” to “the government will take care of it”, but Otago philosophers have been pondering the fairest way of sharing the responsibility.

A research team led by Associate Professor Lisa Ellis (Philosophy and Politics) accepted a challenge from the Deep South National Science Challenge to look at how the risks of sea-level rise should be distributed between individuals, insurance and local and central government in a principled way.

Ellis and two postgraduate students – Lauren Holloway and Britta Clark – considered two main types of risks: the need to secure existing communities against new risks, and the need to limit risky new developments.

“The most important immediate step New Zealand can take towards an ethically robust sea-level rise policy is to bring certainty and consistency into the legislative framework.”

They concluded that, without a new legal framework based on a broad social consensus, the risks in both cases would be transferred from the least to the most vulnerable.

The researchers say that, in the case of risks to existing communities such as the low-lying South Dunedin, “individual members of our most vulnerable communities will bear the burden of risks they could not have foreseen”. In the case of new developments, “government (that is, effectively everyone) will be expected to cover losses for development that is predictably risky”.

“If we stick with the status quo, adjustment to sea-level rise is going to exacerbate existing inequality,” Ellis asserts. “Nobody in New Zealand wants that. They want policy to be in line with consensus ethical values. They want the Government to do what people think is right.”

The researchers identified two ethical values that they believe are particularly important to New Zealanders: that people are treated equally and that they have a say in policy that affects them.

Ellis and her researchers argue that “the most important immediate step New Zealand can take towards an ethically robust sea-level rise policy is to bring certainty and consistency into the legislative framework”.

They say that central government should also resource adaptation to sea-level rise nationwide, so that community resilience does not vary with the ratepayers' ability to pay. And, at a local level, the public should be engaged “as early and deeply as possible” in decisions about their lives.

Deep South is a research collaboration between universities, crown research institutes and other research providers and is one of the government-funded National Science Challenges.

Funding

Deep South National Science Challenge

2

Family worship

Dr Gwynaeth McIntyre: “…people throughout the empire sought to define their relationship with the emperor by connecting themselves with imperial power through priesthoods and cult practices.”

Dr Gwynaeth McIntyre is fascinated by the ways in which mythology and religion were used by members of Roman imperial families to justify and legitimise their power.

“Romans hated kings and so I am interested in how Roman emperors could justify Rome becoming a monarchy and having one man in charge, who is king in all but name, then goes on to become a god after he dies and is worshipped as such throughout the empire.”

McIntyre (Classics) says that her research focuses not just on the worship of Roman emperors, but also on the way their close relatives were turned into gods.

“The practice has been labelled 'emperor worship' or 'ruler cult', but this tells only half the story. Imperial family members also became an important part of this construction of power. Almost half of the 50 or so individuals deified in Rome were wives, sisters, children and other family members of the emperor.”

“Romans hated kings and so I am interested in how Roman emperors could justify Rome becoming a monarchy and having one man in charge, who is king in all but name, then goes on to become a god after he dies and is worshipped as such throughout the empire.”

The youngest of the four children who gained the title of god was Nero's daughter Claudia, who died when she was six months old.

“I was interested in why you would deify small children who have not done anything to deserve it. I think there is something else going on here that is not necessarily power construction, but rather a way of consoling the family.”

McIntyre says that she is particularly interested in how these new gods spread throughout the Roman Empire. Her research focuses on provincial communities in the western part of the empire: in modern-day France, Spain and North Africa.

“As Roman territory expanded and power became consolidated into the hands of one man, people throughout the empire sought to define their relationship with the emperor by connecting themselves with imperial power through priesthoods and cult practices,” McIntyre explains.

“This has been seen as centralised power imposing its will on conquered peoples. In many cases, however, the evidence seems to suggest that local individuals were seeing this mechanism as a way of bettering their social standings within their communities by buying into the Roman dream. And so, they then are the driving force behind setting up priesthoods and building temples to the imperial family.”

She notes that the convention in Rome was that the person had to die to become a god, but provincial communities engaged with the power structure by turning the emperor and his family members into living gods.

McIntyre likens research on ancient Rome to having 10 pieces of a 10,000-piece jigsaw puzzle and no picture of the completed puzzle. The pieces she has been working with include literary sources (in Latin and Greek) written at the time or later, along with stone inscriptions, artefacts and coins.

McIntyre's book embodying her research, A Family of Gods: The Worship of the Imperial Family in the Latin West, has been published by University of Michigan Press.

Funding

University of Otago Humanities Research Grant

3

Youthful hope

Associate Professor Karen Nairn: “We are interested in how hope for social change inspires young people to get involved in collectives and social movements and what keeps them involved.”

The role that hope for a better future plays in motivating young New Zealanders to want to change the world is the focus of a ground-breaking study.

Associate Professor Karen Nairn (Education) is heading a team of researchers from Otago, Victoria and Auckland universities who are keen to discover how young people are putting their hope for social change into action.

“Hope for social change is a powerful catalyst for taking political action,” Nairn says. “Our aim is to understand the role of hope in the politicisation of young people aged between 18 and 29.

“We are interested in how hope for social change inspires young people to get involved in collectives and social movements and what keeps them involved. We also want to explore what issues they perceive as the most urgent, their vision for the future, how they go about negotiating that vision as a group, their views on the most effective ways to make change and how hopeful they are about achieving their vision.

“As a society, it is imperative that we understand what kinds of futures young people are working towards because their hopes and actions could transform the lives of future generations.”

“With things like climate change and Brexit and Trump, there is a lot of media attention on the future and we are interested in what it means to face the future from the perspective of young people, and whether there is the possibility for hope in the context of all the doom and gloom.”

Nairn says that the three-year Putting Hope into Action study is focusing on six groups in which young people are the majority and/or leaders, and are already engaged in collective action with a vision for social change.

“The groups are working across four broad areas: environmental justice, economic or social justice, civil rights including feminist and queer rights, and indigenous rights.” She cites as one example Generation Zero, a nationwide youth-led organisation working towards their vision of a zero-carbon economy.

“There is an inspiring number of diverse groups across the country doing all kinds of really important work, which challenges stereotypes of young people as disaffected, apathetic and self-interested.”

Nairn says that she and her fellow researchers are conducting “activist life history” interviews with up to 15 members of each group and re-interviewing them after 12 months. They are also observing the groups at meetings, during activist events and on social media. Each group will be invited to create a “living manifesto” as a document that articulates their vision for the future, such as a short video clip.

Nairn says that they are setting up a research website to initially engage the participants and then to more widely publicise their findings. They also plan to publish academic articles and a book.

“The project will fill a significant research gap in New Zealand while making an important contribution to international research on politics, new social movements and the role of hope,” Nairn says.

“As a society, it is imperative that we understand what kinds of futures young people are working towards because their hopes and actions could transform the lives of future generations.”

Funding

Marsden Fund

4

The professor and Tartan Noir

Professor Liam McIlvanney: “Twenty years studying and teaching novels has, I hope, given me some insight into the elements of narrative. However, there's no substitute for actually sitting down and writing a novel.”

Professor Liam McIlvanney's lifetime work on Scottish literature has evolved into a passion for creating it as well.

McIlvanney studied at his native Glasgow and at Oxford and taught at Aberdeen before accepting the inaugural Stuart Chair in Scottish Studies at Otago, where he co-directs the Centre for Irish and Scottish Studies, researching the history, literature and culture of the Irish and Scottish away from home.

One of his papers explores “Tartan Noir: Scottish Crime Fiction”, a long tradition of classics from writers such as Walter Scott, R.L. Stevenson and Arthur Conan Doyle to contemporary thrillers. But when McIlvanney began writing his own fiction he stumbled into Tartan Noir territory almost by accident.

“Almost every crime writer seems to have started their first novel without realising that they were writing a crime novel – and that was certainly the case with me. However, once I realised that I was writing crime fiction I happily set about familiarising myself with the conventions of the genre. There's something about the economy and starkness of crime fiction that appeals very strongly to me.”

After academic publishing success – his 2002 study on Burns the Radical won the Saltire First Book Award – McIlvanney's first novel was well received and his second, Where the Dead Men Go, won the 2014 Ngaio Marsh Award for Best New Zealand Crime Novel.

His latest, The Quaker, took the 2018 McIlvanney Prize for Scottish Crime Novel of the Year – an award named in honour of his late father, author William McIlvanney, “the godfather of Tartan Noir”.

Writing fiction has given McIlvanney new insights. “A novel is not 'about' something in the way that an academic monograph is 'about' something. A novel does allow one to tackle subjects in a more open-ended, conditional and interesting manner than is possible in expository prose. Monographs provide answers; novels tend to pose interesting questions.

“One of the things that crime fiction has taught me, as a novelist and academic, is a renewed respect for the power of story. Humans are hard-wired to respond to story.”

“They do have things in common, but they proceed along different routes. Academic writing is incremental: you are patiently building a thesis out of measured, qualified statements that are buttressed by footnotes. Creative writing is a little more free form and spontaneous. You launch yourself out into a passage of prose without always knowing what you're going to say. It's scary, but also exhilarating.

“You encounter a whole different level of exposure as a novelist. An academic monograph will be reviewed in obscure journals and discussed by a self-selecting group of your academic peers. A novel will be reviewed in the pages of the national press, rated on Amazon and Good Reads, and the world and his brother will feel qualified to comment on it. You need to develop a fairly thick skin.”

When it comes to the creative process, the academic and the novelist can exist together comfortably.

“Twenty years studying and teaching novels has, I hope, given me some insight into the elements of narrative. However, there's no substitute for actually sitting down and writing a novel. I have always found that there is a great symbiosis between creative and critical approaches to literature.”

McIlvanney often asks students to compose a short piece of prose in the style of a writer they are studying.

“Creative writing can be a very effective pedagogical tool in the academic study of literature. This brings home to them just how difficult it is to achieve the apparently spontaneous vernacular style of a writer. These are the kinds of insights that can best be generated by creative practice.”

One of the secrets of successful crime fiction such as Tartan and Scandi Noir is that it offers many things to many people.

“People like to experience scary and disturbing things vicariously, in the 'safe space' of fiction. Crime fiction also tends to be more socially engaged than literary fiction, more involved in contemporary 'real-world' issues – and some readers respond to that. But most of all, people like stories and crime fiction provides great stories. One of the things that crime fiction has taught me, as a novelist and academic, is a renewed respect for the power of story. Humans are hard-wired to respond to story.

“In the case of Scotland and Scandinavia, it's the challenge of exposing the criminal underbelly of societies that have traditionally been rather repressed and buttoned up. Crime fiction in these countries is about probing beneath that whole Calvinist/Lutheran façade of respectability. Ideally, as a crime writer, you want a façade to unpeel.”

Ideas come from current and historical events, fleshed out by research from past newspapers, good contacts and wide reading.

“I find, though, that a little research can go a long way. Nothing kills a scene quicker than the sense that the writer is determined to shoehorn his research into the narrative regardless of the dramatic imperatives. And while research has its place, I'm also a great believer in making things up. It's called 'fiction' for a reason.”

McIlvanney's current academic research includes a comprehensive interdisciplinary study of the Scottish dimension to the cultural, political, economic and institutional life of the province of Otago from the colonial period to the present day.

He and collaborators in Scotland and New Zealand aim to challenge Scottish Studies to rethink Scottish history on the international stage.

Funding

Stuart Residence Halls Council