Monday 3 February 2014 5:27pm

Monday 3 February 2014 5:27pmWorms cause more than one billion cases of gastrointestinal infections every year. A simple new device could potentially revolutionise the way in which these parasites can be identified and treated.

It is a simple concept as the best ideas so often are and is set to become a game-changer in the future fight against intestinal parasites that afflict both people and livestock.

At its heart is a tiny tapered glass rod sitting inside a small fluid well. When fluid is put into the well it forms a meniscus a small curved surface of liquid supported by the glass and the well where any tiny worm eggs in the sample will accumulate for easy identification and counting.

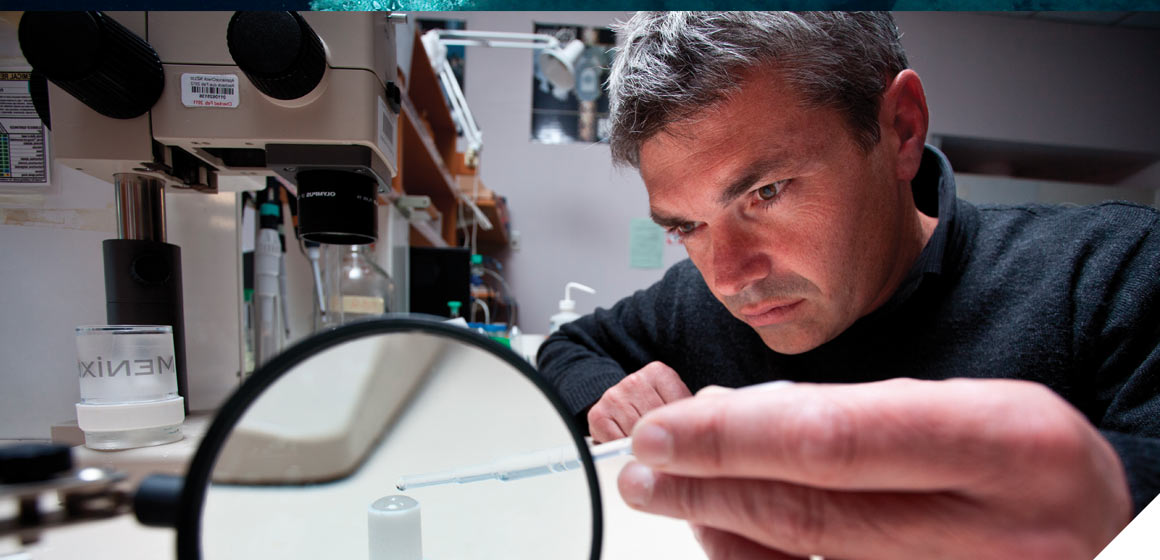

"There are a couple of simple physical principles going on there," explains Dr Stephen Sowerby, Director of Otago's Applied Science Programme.

"Capillary rise causes the fluid to go up the glass rod and, as it advances over the taper, it creates a fluid wedge. Any buoyant particles present in that fluid float up to the meniscus and end up beaching on the glass taper.

"We can shine a light through the glass rod, which illuminates that zone where the eggs accumulate. We can look at that zone through our microscope to identify eggs."

"We decided that rather than going looking for the eggs, why not make the eggs come to you to one place."

Sowerby has worked closely with the Dunedin School of Medicine's Centre for International Health to successfully attract a grant from the Grand Challenges Explorations initiative funded by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, which will allow them to further evaluate the device.

Estimates suggest worms cause more than one billion cases of human gastrointestinal infection and that 450 million of these cases cause significant illness, mostly in children.

In terms of animal health, New Zealand farmers spent about $120 million on drenching last year (as part of an estimated $US2 billion global spend). Despite that, parasites are estimated to cost the country's agricultural producers around $800 million per year. Faster, more accurate diagnosis would allow a more targeted response.

Current monitoring and diagnosis systems use a laborious and time-consuming microscopy for identifying eggs on a slide, but the system developed by Sowerby and his colleagues is faster and simpler, plus it can be used in the field.

"We decided that rather than going looking for the eggs, why not make the eggs come to you to one place.

"What we do is we take away the technical burden on the person doing the microscopy."

The new device also allows the results of each sample to be captured as a single image, something that was not easy previously. That image can be captured on something as everyday as a cell phone then be sent around the world to be examined by experts whereas, with the old slides, the person doing the analysis had to be the expert.

Data can also be kept for later auditing. In addition, it means potentially infectious material doesn't have to be transported from place to place.

"Most of the samples have no parasites so the traditional microscopy is a lot of work to find nothing. With this system, in a matter of five seconds I can say there is nothing in there," says Sowerby.

The device was developed in conjunction with the Dunedin-based Techion Group and, together with Otago Innovation Limited, they have set up a company called Menixis to commercialise it.

They have also worked closely with local engineers DC Ross and Lincoln Agritech to develop a simple machine to do the imaging.

Sowerby says they first started work on the concept in 2008 and now have a capitalised company making a product.

"Most technology start-ups are generally 10-15 years. We engaged with the market right at the very start. If you don't have that early end-user engagement, what you develop starts to drift away from what the end-user wants. That is critical."

Funding

- Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation

- University of Otago

- Otago Innovation Ltd

- SIP Ltd

- Techion Group Ltd

- Enterprise Angels