Professor Robert Patman:

Professor Robert Patman:

"America's post-Somalia approach was supposed to be about putting the interests of national security first. Instead it came back to bite them."

Where travel was once an eagerly anticipated adventure, it is now an exhausting and frustrating battle with bureaucracy, border security and body checks. It's just one way that international terrorism and the politics of fear have changed the world.

The American response to the 9/11 attacks on the twin towers of the World Trade Center in Manhattan is often said to have introduced a new strategic era in US foreign policy that has resulted in global insecurity. But that view is profoundly mistaken, according to Robert Patman, Professor of International Relations and director of the Master of International Studies programme at the University of Otago.

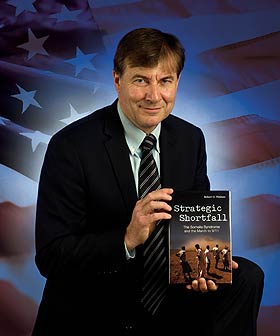

Patman, a leading expert on US foreign policy in the post-Cold War security environment, outlines his ideas in his recent book, Strategic Shortfall: The Somalia Syndrome and the March to 9/11.

He locates the origins of 9/11 in the increasingly globalised security context of the early post-Cold War period, arguing that the disastrous US–UN humanitarian intervention in Somalia in 1992– 1993 was a defining moment for US foreign policy. It generated the Somalia Syndrome, a risk-averse approach to involvement in civil conflicts, especially if US casualties were likely.

This had significant international fall-out, says Patman, including encouraging the Osama bin Laden network to gradually escalate its terrorist campaign against the US. Washington policy choices made between 1993 and 2001 created a strategic shortfall that enabled al Qaeda to grow to the point where it was capable of mounting the devastating terrorist attacks of 9/11.

At the end of the Cold War, an optimistic America had initially envisaged a new world order based on a partnership between US power and UN authority. But the experience of the savage confrontation in Mogadishu between US forces and armed supporters of warlord General Aideed in October 1993 fundamentally changed the direction of US foreign policy.

Television pictures of naked dead US servicemen being dragged through the streets of Mogadishu by followers of Aideed appalled and angered many Americans and prompted the then President, Bill Clinton, to bow to pressure to withdraw US troops from strifetorn Somalia.

Above all, says Patman, Somalia taught the Clinton administration that most failed states or failing states were not vital to the national security interests of the US and could not, by themselves, be allowed to define America's broader strategy in the world.

America's subsequent foreign policy caution in places like Haiti, Rwanda and Bosnia allowed hostile militant organisations like al Qaeda to grow in size and confidence. Al Qaeda had held a grudge against the US since the first Gulf War, when the American troop presence in the holy land of Saudi Arabia had offended the religious concerns of the bin Laden network.

However, it was the Somalia Syndrome that served as a major catalyst in emboldening al Qaeda to purse a global terrorist campaign against the US. For the al Qaeda leadership, the central lesson of Somalia was that "the Americans will leave if they are attacked".

More specifically, because some al Qaeda operatives were involved in the Mogadishu showdown, the leadership of the bin Laden network believed it had actually created the Somalia Syndrome that reversed US foreign policy.

So the Somalia Syndrome marked the emergence of a dangerous gap between America's reinvigorated national security outlook and the transformed security environment of the post-Cold War era, characterised by the rise of new transnational challengers like al Qaeda.

"America's post-Somalia approach was supposed to be about putting the interests of national security first," says Patman. "Instead it came back to bite them.

"The Americans learned the wrong lessons from the firefight in Mogadishu by seeing their world as they wished it rather than actually seeing it as it really was.

"They didn't revise their attitudes despite a series of terrorist attacks on US personnel and interests in various parts of the world during the 1990s. They had not learned that failed states elsewhere were a threat to US internal security. You can't go it alone in an interconnected world."

Then came 9/11, which should have been no surprise. "As soon as George W Bush became President there were repeated high-level warnings about a terrorist attack on the scale of 9/11. But these were largely ignored."

Ultimately, says Patman, 9/11 was more about a failure of policy than about the limitations of America's intelligence agencies or the laxity of its airport security. The roots of this policy failure lay in the advent of the Somalia Syndrome after 1993.

President Bush claimed it was 9/11 that transformed America's strategic thinking overnight and declared a war on terror. But, by obscuring the origins of 9/11, the Bush administration embraced policies that played into the hands of the bin Laden network. "The invasion of Iraq in 2003 seemed to confirm al Qaeda's propaganda that America was at war with Islam, rather just the people responsible for 9/11," says Patman.

"Strategic Shortfall may be a non-American view of the crucial period leading up to 9/11, but the findings of the book have been well received internationally."

Since publication, Patman has outlined his argument at universities in six countries and has spoken to a number of US institutions including the David M Kennedy Center for International Studies, Brigham Young University, Purdue University and the John F Kennedy School of Government at Harvard.

Strategic Shortfall is Patman's eighth book, but his first singleauthored volume with an American publisher, Praeger. Despite his international reputation as a scholar and analyst, he admits, "the American market is a difficult one for many academics to break into".

So plaudits from American academics and military are well-earned, particularly from retired US Army Colonel Martin Stanton, who writes in the foreword to Patman's book: "I certainly learned things I didn't know, even though I was there."

Funding

University of Otago Research Grant