Monday 3 February 2014 11:37am

Monday 3 February 2014 11:37amUniversity of Otago expertise is contributing to a greater appreciation of the efforts of New Zealand tunnellers in France during World War I.

School of Surveying staff members Dr Pascal Sirguey and Richard Hemi, and postgraduate student Chris Page, are collaborating with their peers from the École Supérieure des Géomètres et Topographes (ESGT), in Le Mans, to survey and virtually replicate tunnels which members of the New Zealand Engineers Tunnelling Company secretly dug at Arras in northern France in 1916-17.

The company started with 446 men, mostly miners from places such as Waihi, Huntly and the West Coast, along with men from the Public Works and Railways departments and the New Zealand School of Mines at the University of Otago, supported by other defence personnel, including the New Zealand (Māori) Pioneer Battalion.

They were already in France, undermining German trenches, when an audacious scheme was devised to link historic underground chalkstone quarries that had been mined for building material, to create a vast military complex, an average of about 15 metres below the surface, running 2.3 kilometres from Arras under no-man's-land to the German trenches.

After five months, the Ronville network of quarries and tunnels was able to quarter up to 9,500 troops and supplies. It had electric lighting and running water, kitchens and toilets: it even boasted its own light rail.

In the lead-up to the Battle of Arras, the complex accommodated British troops for a week and allowed them to advance safely for a surprise attack up through assault tunnels at the German front line. It enabled a quick advance to another stalemate.

Hemi says that French people subsequently used the complex as bomb shelters during World War II and viewed it as a potential nuclear fall-out shelter during the Cold War. Sirguey notes that it also served as an underworld playground for local children, before access was restricted and a museum was developed in one of the quarries.

Two-dimensional maps had been produced of the labyrinth, but after hearing about the New Zealand connection Hemi came up with the idea of creating realistic three-dimensional modelling of the tunnels using a terrestrial laser scanner.

He enlisted Sirguey, who was already lecturing at Otago and has expertise in remote sensing, with the added advantage that he is from France.

Sirguey secured the funding and turned the project into what the pair describe as a very successful French-New Zealand university collaboration.

Combining the latest in high-tech terrestrial laser scanners – a Trimble TX8 – with a single lens reflex camera for realistic colouring, the team has surveyed roughly half of the complex that is accessible: roof collapses and safety considerations put the rest out of bounds. The team has also surveyed the landscape above ground to enable people to reference the exact location of the quarries and tunnels.

Hemi explains that the laser scanner is capable of measuring a million points per second, using the delayed return of reflected light. Hundreds of scans from different locations are then stitched together to create what is called a “point cloud” of the complex.

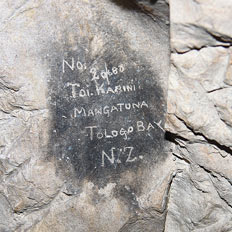

Although the work is very technical, it also has a strong emotional component. Hemi was particularly affected by seeing so many New Zealand references, including Māori words carved into the walls, sketches of sweethearts back home, and the New Zealand placenames for the quarries the tunnellers used to help with underground orientation, from north to south, Russell to Bluff.

“You are certainly aware of the graffiti and the sadness of men who have perhaps written their last farewell on a chalk wall,” Hemi acknowledges. “Finding survey marks and writing in the ceilings that could have been put there by surveyors trained at Otago was a really touching connection. Coming from New Zealand, there was also an element of pride.”

“For me, it was very moving to realise that Kiwis 100 years ago travelled this far and put their lives on the edge so close from where I grew up,” Sirguey recalls.

The team is progressively making the results of its work publicly available, notably via a dedicated website.

There are also ambitions for individuals to be able to take virtual reality tours of the complex. The team will showcase its work at the Battle of Arras centennial commemoration at Arras in April 2017.

They are relating some of the more specialised information about the project through conference papers and academic journals. Sirguey adds that the information will be freely available to researchers from different disciplines, such as geologists, archaeologists, historians and computer scientists.

Time and urban development are taking their toll on the chalk complex, but the work of the Otago and ESGT academics is highlighting the importance of protection, and ensuring a permanent digital record of the extraordinary subterranean system and those who shaped it into a significant military and cultural heritage site.

Funding

- Lottery World War I Commemorations, Environment and Heritage Committee

- New Zealand-France Friendship Fund

- University of Otago