Although the University of Otago was the first university in New Zealand, it was the last to establish a Māori Studies Department, in 1990. From a relatively small department we have grown into a School, which currently offers undergraduate and postgraduate study to PhD level in three programmes: Māori Studies, Pacific Islands Studies, and Indigenous Development, as well as the Master of Indigenous Studies, tailored especially for distance students.

Although the University of Otago was the first university in New Zealand, it was the last to establish a Māori Studies Department, in 1990. From a relatively small department we have grown into a School, which currently offers undergraduate and postgraduate study to PhD level in three programmes: Māori Studies, Pacific Islands Studies, and Indigenous Development, as well as the Master of Indigenous Studies, tailored especially for distance students.

While it is possible that informal teaching of te reo Māori may have occurred earlier at the university, the Department of University Extension first noted that it was offering a course in 1957, with Harold Tarewai Wesley of Ōtākou as the first tutor. Its annual report stated: “For the first time a course was offered in the Maori language; this was well attended by members of the local Maori community.” The courses continued through into the 1970s under a number of different teachers, including lecturers at Knox College, who had served as missionaries in the Presbyterian Māori Mission. In 1974 the role was taken up by Muru Walters, a lecturer at the College of Education, who later went on to become a bishop within the Anglican Church.

It was in the early 1970s that the university first started investigating the teaching of te reo Māori as a standard university course, but it was not until 1981 that classes started (capped at 32 students), pioneered by Dr. Ray Harlow from the Linguistics Department. Ray Harlow later served on the board of Te Taura Whiri i te Reo Māori, and is now Professor Emeritus at Waikato University.

The university appointed Godfrey Pōhatu in 1986, followed soon after by his wife Toroa Pōhatu. The cap on numbers was lifted, and 103 students enrolled. In 1989 200-level papers were offered, and in the following year, Māori Studies emerged as a fully-fledged department, known as Te Tari Māori, with 300-level papers followed by its first graduates. Offerings not only included te reo Māori papers, but also courses on Māori history, tikanga and other aspects of te ao Māori. The Department also experienced strong growth: by 1994 it had 1100 students enrolled in its courses, eight lecturing staff, three teaching fellows and thirty tutors.

Māori Studies staff in 1991. Standing (from left): Mark Laws, Maureen Bruce, Godfrey Pohatu, Meredith Boag, Michael Reilly, Mereana Smith. Seated: Lorraine Johnson, Toroa Pohatu

Māori Studies staff in 1991. Standing (from left): Mark Laws, Maureen Bruce, Godfrey Pohatu, Meredith Boag, Michael Reilly, Mereana Smith. Seated: Lorraine Johnson, Toroa PohatuGodfrey Pōhatu was a skilled composer, and his tenure was noted for Te Kapa Haka o Te Whare Wānanga o Ōtākou that he and Toroa ran. This cultural group, that competed at a number of competitions, attracted not only students and staff but also many people from the wider community. Indeed Godfrey and Toroa were well-known for their generosity, their engagement with Māori students and with Māori public events. Godfrey's vision for Te Tari Māori, was that it was “first and foremost an academic programme that teaches, researches in, and supports the linguistic, cultural, social, and historical circumstances of the Maori people—as a collective entity—of this country”. He went on to complete a PhD at Ōtāgo in 1998. Sadly he passed away in 2004.

In 1996, the university appointed Tania Ka'ai as the Chair of Māori Studies, the first Māori woman to attain such a position, as acting Head of Department. Tānia Ka'ai quickly became the permanent Head, and her tenure saw a number of developments. Māori Studies was withdrawn from the Department of Languages, where it had been attached from 1994. Professor John Moorfield was appointed in 1997, and his Te Whanake system of Māori-language learning was soon implemented at all levels. The status of Māori Studies also changed from “department” to “school”, with Ka'ai becoming Dean. In 1999 the school acquired the name “Te Tumu”. Professor Wharehuia Milroy, an eminent Māori-language expert who has maintained strong links with Te Tumu, offered the name, deriving from “te tumu herenga waka”, the post at which canoes are tied. It is a name that also resonates within the Pacific.

Many from this era will no doubt remember the promotional trips to various tribal districts around the country. Between 2001 and 2006, busloads of students and staff visited Waikato and Tūwharetoa, Ngāti Kahungunu ki Heretaunga, Te Wai Pounamu, Taranaki and Ngāti Tūwharetoa. While of course there were inevitable dramas, it was a great opportunity for students to experience the hospitality and kawa of a number of marae around the country.

The new millennium also saw new academic developments. In 2003 Pacific Islands Studies was introduced as a subject area. Michelle Saisoa'a (now Dr Michelle Schaaf) had been teaching in the department since 1999, and it largely fell to her to develop the new programme. In 2003 Dr Brendan Hokowhitu introduced the Master of Indigenous Studies (MIndS) programme, which further widened the Te Tumu's focus from its Māori Studies roots. Three years later, the MIndS became an online programme, and many people, from within New Zealand, Pacific countries, and further beyond, have been able to take advantage of an Otago masters degree without having to leave their homes. A number have also moved on from a MIndS degree to successfully complete PhDs. It was with the development of these two new programmes that Te Tumu became the School of Māori, Pacific and Indigenous Studies.

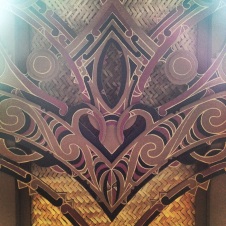

2006 saw two further developments. The first was the development of the Bachelor of Māori Traditional Arts degree. This was envisaged as having two main streams: toi whakairo (carving) and ngā mahi a te whare pora (weaving), with students also engaging with tikanga Māori, te reo Māori and Māori performing arts. The second development, which largely enabled the first, was the new Te Tumu building. Prior to this, Te Tumu had been squeezed into the small buildings on the edge of the Burns carpark. The Traditional Arts teaching was enabled by the space on the tenth floor; students can engage in waiata classes in the ground-floor performing space, and hospitality can be provided from Te Tumu's kitchen and dining space on the first floor. Unfortunately the Bachelor of Māori Traditional Arts programmes did not prove to be economically viable. Despite a number of people graduating with the BMTradArts, the degree was terminated in 2010.

Professor Ka'ai's tenure as Te Tumu's dean ended in 2007, when she and Professor Moorfield moved north to AUT in Auckland. The Pro-Vice Chancellor Humanities, Professor Alistair Fox, and then Te Tumu's Associate Professor Michael Reilly held the role of dean temporarily until 2009 when Paul Tapsell was appointed as the new Dean and Chair of Māori Studies. It was at this time that Michael Reilly was promoted as a full professor.

Professor Tapsell's tenure is notable for the introduction of Indigenous Development as a BA major. Not all students could cope with the strong language focus of the Māori Studies major, yet still wanted to engage with topics relating to te ao Māori and other indigenous societies. This new programme has been particularly successful.

Professor Michael Reilly assumed the role of Dean in 2012, when Paul Tapsell stepped down to focus more on his research projects. Michael was one of the original staff members of the Department in 1991, a joint appointment in Māori Studies and History until 1996, and has held a number of roles within the School. Practically all of Te Tumu's graduates will have experienced Michael's teaching at some level, but his legacy goes far deeper, including supervising 55 History or Māori Studies students at postgraduate level. In his 24 years in Māori Studies and Te Tumu, Michael has been one of the people who, through his hard work, has made a lot of new developments happen. Michael has also been the key individual who has built Te Tumu's academic foundations, and promoted academic leadership.

In 2000 only three Te Tumu staff had PhDs, Michael Reilly being one of them. Today, of the 16 permanent academic staff, 12 now have PhDs. Of this twelve, Michael has supervised five: Professor Poia Rewi (current Dean of Te Tumu), Associate Professor Lachy Paterson (Associate Dean Graduate Studies), Drs Michelle Schaff, Paerau Warbrick, and Karyn Paringatai. He also supervised several past staff members who have taken up leadership positions at other universities/wānanga, including Professor Rawinia Higgins, Pro Vice-Chancellor Māori at Victoria University of Wellington, and Professor Nathan Matthews, Head of School - Indigenous Graduate Studies at Te Whare Wānanga o Awanuiārangi. Te Tumu's success can largely be traced to Professor Reilly's input.

Dr Michelle Schaaf. In 2011 Michelle became the first staff member at the University of Otago School of Maori, Pacific and Indigenous Studies to graduate with an Otago doctorate in Pacific studies.

Dr Michelle Schaaf. In 2011 Michelle became the first staff member at the University of Otago School of Maori, Pacific and Indigenous Studies to graduate with an Otago doctorate in Pacific studies.Photo: http://www.odt.co.nz/

Te Tumu has now reached its first quarter century, evolving from Te Tari Māori through to a School of Māori, Pacific and Indigenous Studies. The School has strong links with Kāi Tahu, and works in conjunction with the university's Māori and Pacific initiatives, such as the Office of Māori Development, Te Huka Mātauraka/Māori Centre and Pacific Islands Centre. As Te Tumu has progressed, our academic courses have also developed, with papers currently being offered in te reo Māori, tikanga Māori, Ngāi Tahu, Māori education, Māori history, Māori performing arts, Treaty of Waitangi, Indigenous leadership, Indigenous development, and the peoples and cultures of the Pacific.

SourcesAli Clarke, “Beginnings of te reo Māori”, University of Otago 1869-2019 ~ writing a history, https://otago150years.wordpress.com/2014/07/21/beginnings-of-te-reo-maori/Ali Clarke, “Maori Studies celebrates”, University of Otago 1869-2019 ~ writing a history, https://otago150years.wordpress.com/2015/03/16/maori-studies-celebrates/Michael P.J. Reilly, “What is Māori Studies?”, OUR Archive, https://ourarchive.otago.ac.nz/handle/10523/5159Michael P.J. Reilly “Maori Studies, Past and Present: A Review”, The Contemporary Pacific (September, 2011), http://www.highbeam.com/doc/1G1-263440685.htmlThe History of Te Tumu, Te Tumu, 2006.